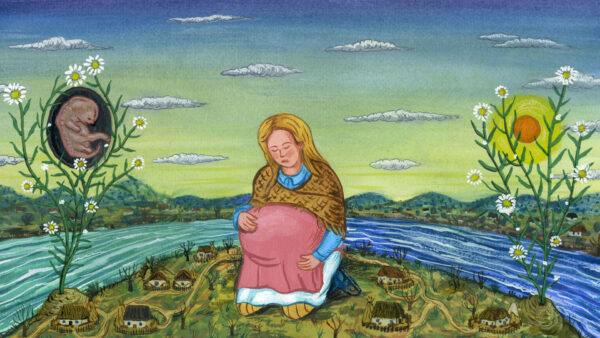

A Militantly Human Dementia Tale

Late Winter

Not sure where to look and cut, Jasna Safić’s portrait of an old man suffering from a mental illness makes up for its shortcomings by embracing a selfless humanity.

Are we (in)capable of caring for our relatives when their health goes south? A portrait of an old man suffering from a mental illness and of the relatives who must look after him, Jasna Safić’s Late Winter suggests that outsiders may be better equipped at tending to a person on the decline than those closest to them. So it is for Vlado; his wife and forty-something son Šaša have long supported him in his battle with dementia, but are now finding the task increasingly exhausting. As the two grow desperate over Vlado’s urge to leave the house, the onus is upon the old man’s daughter-in-law Selma to try and connect with him. Safić’s film doesn’t always know where to look and cut, but makes up for these shortcomings by embracing Selma’s own selfless humanity.

A medicinal researcher, Safić’s background informs her portrait of bed-ridden Vlado, whom the writer-director refuses to paint as a man defined by his condition. Instead, she sidetracks the de-personalizing stigma of his mental illness, without glossing over the pain and frustration that come with it. The old man’s wife and son don’t know what to do anymore, and the film shows they have every right to feel that way. But Late Winter also doubles as a reminder that it is never too late to share an intimate moment, no matter how far gone someone is.

Selma’s recently filed for divorce; she has no reason to help Vlado, but insists on doing that anyway. While her soon-to-be ex-husband shies away from any attempt to connect with his father, she takes time to listen and talk to him. The different approaches make for an interesting study of self-sacrifice, with Posavec’s gaze and posture wavering between vulnerability and sternness, making her all the more enchanting. She shows that there can still be depth in their conversations. Her words and gestures become heartbreakingly poetic in their final exchange, which reads like a haunted poem. “Madam, can’t you see how crowded it is?”, Vlado asks Selma as the two sit in an empty living room.

Yet Late Winter is only intermittently poetic, and a few shortcomings in the technical departments routinely threaten to yank the spectator out of the drama. The short was shot by Antonio Pozojević; it is filled with inserts and cutaways that lack the soul of the characters that inhabit them, and whose pacing editor Filip Antonio Lizatović doesn’t establish as well as he does in the conversational scenes, which themselves aren’t always cut continuously. Most of the cutaways feel interchangeable or redundant, so much so that the film seems to rely on them because it often doesn’t seem to know where to go next.

The widespread use practical lights, which litter almost every interior frame, decentralise the sense of loss we should be registering as well as the way we should read these shots. The actors’ silhouettes lack focus because they’re grossly mis- or under-lit, which could add another layer of theatricality if the performances weren’t played right. Fortunately, this is really where the film shines bright. The four actors all embrace the same naturalism needed to avoid over-romanticizing the subject matter. Šivak’s negligence, Ipša’s desperation and Savić’s fatigue beg to be empathized with, while Posavec’s austerity informs the short’s rhythm and tone.

Selma begins to strum a guitar; her pickings swell the lounge with echoes of a long-forgotten folk song. It’s a sad and touching melody, as if composed by a pilgrim who has long lost their way. Safić leaves you feeling bittersweet as she helps the film’s own weary traveler clear his head for a bit and fall back on the cushions, lulled by Selma’s tune. Pozojević lets the sunlight pour into the film’s closing frames—a thawing landscape welcoming spring again. It’s all a little grim and the cold won’t go away just yet, but it makes those timid rays of sunlight, those small moments of clarity, all the more soothing.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #2—a tandem workshop set during Lago Film Fest and FeKK Ljubljana International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Leonardo Goi.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!