A Lithuanian Avant-Garde Legend, Resurrected

On the Works of Artūras Barysas

In 2024, Artūras Barysas’s rebellious chronicles of the Soviet regime were finally screened again in his hometown of Vilnius, after gathering dust on the shelves for many years. Posthumously, the Lithuanian avant-garde legend reclaimed his rightful recognition.

“Ssshhh: No Fun At The Seated Discotheque” was the name of a special programme at the Vilnius Short Film Festival 2024, a retrospective of the late filmmaker, actor, singer, and mélomane Artūras Barysas (1954-2005). Known as the father of modern Lithuanian avant-garde, Barysas (or simply, Baras) was a Vilnius persona first and foremost, easily recognisable in the streets and known among punks, drunks, dissenters, as well as amateur filmmakers, who slipped through the cracks of the rigid Soviet regime.

In Soviet-era Lithuania, amateur cinema provided a space for creative freedom and served as a vital tool for resistance. Unlike professional filmmakers, Barysas did not have to undergo the same scrutiny by the state censors: “Simply, no one would edit amateur filmmakers’ scripts as it was done in professional cinema because you wouldn’t allow them [censors 11 In the Soviet-era Lithuanian cinema, there was no single institution regulating censorship activities. The supervision of film production was overseen by a multi-level apparatus encompassing both Soviet Lithuanian and Soviet Russian institutions. [Kaminskaitė-Jančorienė, Lina. “Kino Kūrimo Užkulisiai: Cenzūra ir Kontrolė”, The MO Museum http://www.mmcentras.lt/kulturos-istorija/kulturos-istorija/kinas/19611969-autorinio-kino-modelio-isigalejimas-lietuviu-kine/kino-kurimo-uzkulisiai-cenzura-ir-kontrole/78937, Accessed April 26, 2024.] ↩︎] to read it,” once attested Barysas. Baras epitomised non-conformity in his work, pushing boundaries from one of the earliest instances of nudity in Lithuanian cinema to the inclusion of Western symbols on screen. Borrowing its name from the Vilnius University Physics faculty underground event from the 1980s, during which Barysas presented his incendiary films, the VSFF programme showcased seventeen such experimental shorts. The films date from 1972 to 1982, examining one of the decades of Soviet oppression, of which Lithuania’s later generation knows from history books and half-told family tales, yet nothing tangible. After gathering dust on the shelves for thirty years, these rebellious chronicles of the Soviet regime have been digitised and now have received their opportune moment to be shown in Lithuania and beyond.

Paradoxically, Barysas never intended for his films to appear in cinemas. Illegal or purely inaccessible music records released in the West were an integral part of this nonconformist’s shorts (and his life): “Music is the cinema language of heroes,” stated Barysas in his autobiography, written in one sitting in the autumn of 2003. The use of world-renowned artists’ tracks in his films made it impossible to show them publicly. Today, it also becomes difficult to trace back which scores Barysas, an avid fan of bands such as Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and Black Sabbath, used as original scores. In 2022, several prominent Lithuanian composers were commissioned to score the films again, creating alternative soundtracks for the shorts and thus facilitating their reintroduction to the world.

Thanks to Vilnius Short Film Festival and these newly composed soundtracks, Barysas’ films were finally able to reach the Vilnius public at the screening that took place in the SKALVIJA Cinema Centre, an intimate one-screen cinema and the quintessential hub for the city’s cinephiles. Nestled along the Neris riverbank, this locale carries a symbolic resonance for everyone who’s been there. Formerly known as Planeta, the cinema boasts a legacy dating back to the 1960s, having been operational during the Soviet era. As this historic screening space welcomed renowned composers, local artists, and other freethinkers to Barysas’ retrospective, and the audience not only filled the cinema seats but spilled onto the floor, the event emerged as a monumental, once-in-a-lifetime spectacle. The cinema that was once part of the ruthless Soviet propaganda apparatus welcomed Baras’ anti-establishment works with applause. Barysas, nineteen years after his passing, reclaimed his rightful recognition.

The seated disco commenced with The Essay (1981), an experimental film-revolt. Featuring snippets of a couple pushing a stroller, the film gradually revealed them in clothing adorned with the USA flag and stars. Through cryptic black-and-white shots, they were captured smoking Marlboro cigarettes, reading adult magazines, and sipping on Coca-Cola, a beverage restricted by the Soviet government due to its perceived association with American imperialism. Maybe, in this cinematic endeavour, Barysas emerged as a visionary ahead of his time? The film’s imagery, captured in obscurity, seemed to resonate with contemporary Lithuanian society, reliant not only on the consumption of Western goods but also on the protective umbrella of NATO. Indeed, both in its historical context and in the present day, The Essay possesses the transformative power to render its audience speechless, especially when considering the era in which it was created and the potential repercussions Barysas could have faced under the stringent Soviet regime for this provocative film alone.

© We (Artūras Barysas, 1980)

But if one wants to look at Lithuania’s past and not the present, Artūras Barysas’s 1980 film We offers a direct and unembellished documentation of the Lithuanian Soviet era. The film captures the 9th of May military parade in Vilnius and communists celebrating the liberation from ‘fascism’ in an occupied city. I find it challenging to articulate the emotions stirred among the Lithuanian audience during our collective viewing. For both those who vividly recall that period and those born shortly after, the painful imagery concealed for so long came to the fore. As the screen unfolded with scenes of crowds, all complicit in our legacy of trauma, wearing communist uniforms and medals, jubilantly marching through the capital’s streets, a certain restlessness permeated the audience. A spontaneous exclamation of “Oh, pigs!” reverberated through the space. We witnessed Vilnius’s historical tapestry, as Barysas’s camera zoomed in and out, recording the now communist anti-heroes alongside the unsettling images of a child in red clothing waving a USSR flag, and a congregation of soldiers and politicians placing flowers next to our butcher Stalin’s statue, once proudly displayed at the heart of the town.

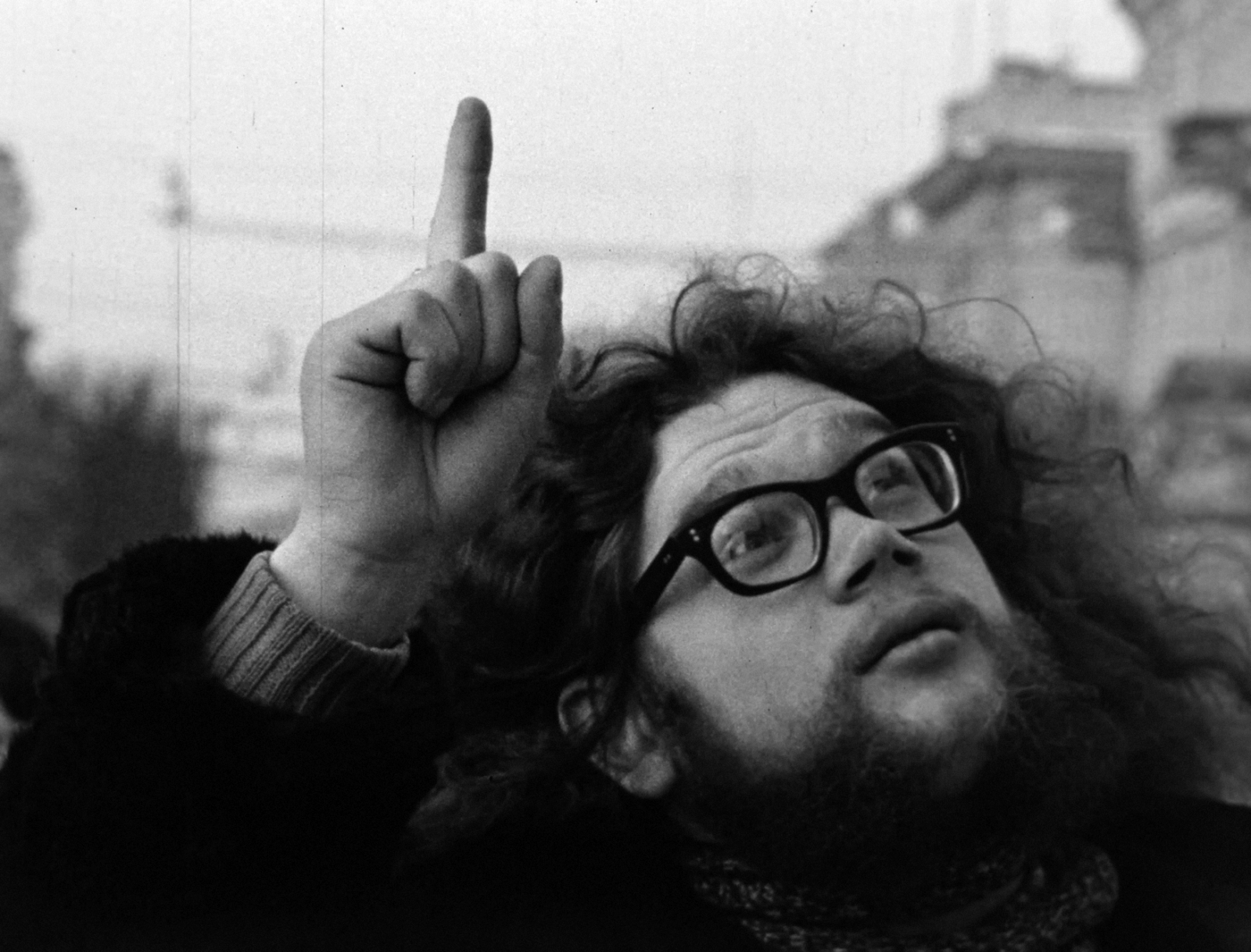

While We stirred a cascade of questions and set the evocative political tone for the rest of the programme, in a true Barysas fashion, through jest and play, the following films in the retrospective were ready to elicit ambiguous responses to what we really were and are. In Those Who Do Not Know, Ask the Ones Who Do (1975), Barysas, who regularly appeared in his shorts, was pointing to the sky and to the ground as crowds gathered and jostled near Vilnius Cathedral Bell Tower. The film spoke to the post-Soviet viewers through enigmatic shots of passers-by, suspiciously staring back at us and breaking the fourth wall, as if made uneasy by our gaze.

Similarly, That Sweet Word (1977), a one-minute microfilm, employed yet another metaphor to describe the regime. The film was a direct response to That Sweet Word – Liberty! (1972), a film by Vytautas Žalakevičius, one of the most prominent Lithuanian film directors of the Soviet era. In 2001, in a cultural weekly Šiaurės Atėnai, Barysas explained that Žalakevičius’s film truly upset him and compared it to “political prostitution”. The omission of a particular word in the name serves as the primary signifier here. That Sweet Word depicts Barysas in tight frames, scaling an iron gate in a desperate attempt to break through to the other side. However, a deft zoom-out reveals that the remaining gate stands within a concrete frame, isolated, with entrances accessible from both sides. Might Barysas have foreseen that his films would serve as a bridge between generations, both trapped in the struggle for freedom and uncertain of their direction?

Yet, in this extensive retrospective, it becomes clear that not all of Baras’s works carried overt political connotations; some were whimsically light-hearted. One such gem was the micro-short The Anecdote about the Meter (1978), a delightful Chaplinesque vignette that showcased Barysas in a comical pursuit of a “meter of coffee”. In the film, Barysas poses this quirky request, and the waitress, after pondering for a moment, pours a line of coffee onto the table. Barysas measures it, and a title card appears: “Pack it up, please.” Filled with exuberance, the waitress seizes Baras by the collar and leads him to a sign that reads, “Strictly Prohibited to Take Away”. In a close-up shot, a girl in the café bursts out laughing. Intriguingly, the film synopsis at the VSFF programme refers to The Anecdote about the Meter as “a Dadaist parody of real socialist service”. I wonder whether Barysas would contradict or confirm; his humour is uniquely his own: “I understand that many, if not most, don’t catch on to it,” he wrote. While open to interpretations, the film, crafted under the oppressive regime, certainly allowed for laughter.

© That Sweet Word (Artūras Barysas, 1977)

The culmination of the programme was marked by The Earth, Planet of People (1972), one of Barysas’s most cherished works. The short has been considered long lost and was newly discovered and restored by one of the programme curators, Lijana Jakovlevna Siuchina, who, according to fellow curator David Ellis, not only breathed new life into the film but crafted an entirely new cinematic experience. The clearer, crisper image lacked the original soundtrack that Barysas intended for it, and was screened as silent: “It’s such an extraordinary document of the period, it requires no extra cherry on top,” explained Ellis.

I remember first seeing The Earth, Planet of People online with an upbeat, unofficial score. At the Vilnius screening, the film, stripped down from diversions and imbued with the context of Barysas’s previous films, presented itself as something entirely different. As the camera moved through the streets of Vilnius, capturing women purchasing papers from an eccentric kiosk attendant, children laughing and playing, and young people dancing, I felt a certain melancholy. It became challenging to envision the joy Barysas sought to portray, a happiness positioned as a form of resistance within the confines of the regime. Perhaps, his talent is still confined to the basements where the real seated discos took place? “It’s a shame that the dreamed and fought for freedom did not liberate the person as a creator,” attested Barysas in a 2001 interview.

As the vibrant images of Vilnius residents unfolded on the screen, I couldn’t help but hope that these moments would linger in the audience’s memory, potentially superseding the recollection of communist marches through the same streets. It became evident that both homines sovietici and the post-Soviet generation yearned for positive memories of that era—memories that defied the sanctioning of remembrance. The Earth, Planet of People served as a fitting conclusion, the final Barysas offering to the festival audience, extending a pathway for such remembrance. “I was there myself,” recalled Barysas’s life-long friends, the last of Vilnius’ bohemia; they talked over each other, contradicted, and contributed to the stories about Baras: the artist, the maverick, the jokester. It became abundantly clear that Artūras Barysas was, and remains, a legend.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #3—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.