A Prison of Letters

Love, Dad

Diana Cam Van Nguyen’s festival hit is a personal story that becomes one of intergenerational and -cultural confrontation.

Epistolary correspondence and cinema have always been a shaky marriage. Protagonists in films of frugally gifted filmmakers all too often reach for their quill, pen, or keyboard to melodramatically reveal their emotions to their objet du désir or distant pen pal–often paired with whispered voice-overs, so the audience doesn’t have to read. Be that as it may, letter writing can also pursue the highly cinematic. Not only do we experience the passage of time—the long wait for an answer, the slow dialogue—the letter itself, the object even more than the ‘archaic’ medium of communication, carries a particular burden.

We often see small boxes of letters found in dusty attics in films. Close-ups on curly letters that, years ago, gently let their secrets sink in the yellowish, discolored paper: a metaphor for the slow fading of memory? Writing a letter presupposes intimacy and the private stirrings of the soul, yet should not be limited to that. Stationery can also carry deceit or pretense, a kind of shield behind which the writer can hide.

Czech-Vietnamese filmmaker Diana Cam Van Nguyen also finds letters from the past. Fifteen years ago, her father was imprisoned. The affectionate messages he sent her from jail in those days prompted her to write a response on January 20, 2020. As befits a graduating student at the famous Prague film school FAMU, this is done in film form–or at least after the letter she wrote struck her for too long and, above all, too harsh.

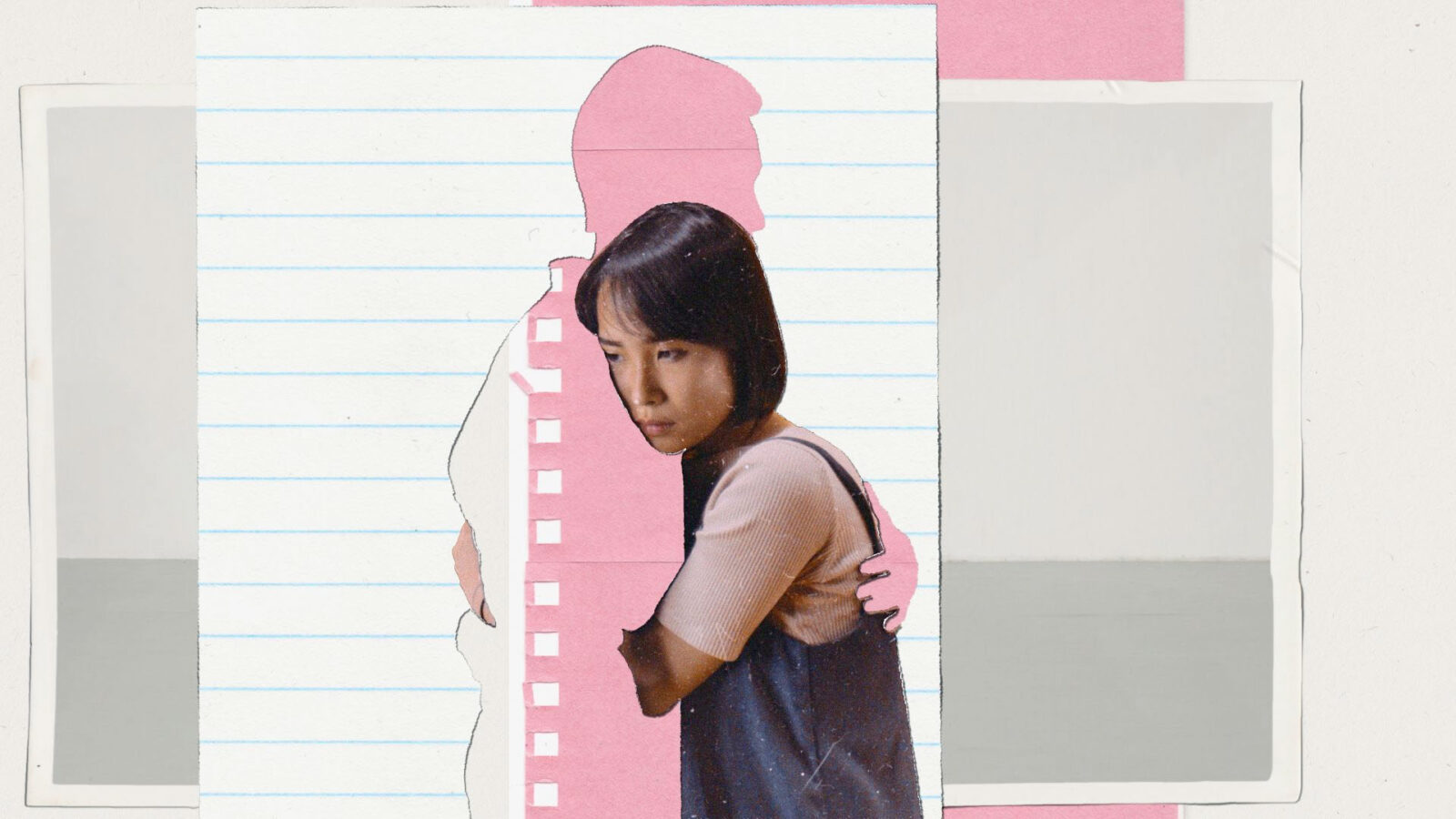

Van Nguyen heaves not only the collection of her father’s letters but also boxes full of old family albums, children’s drawings, and postcards from the storage room to answer the man and reflect on their complicated relationship. This hyperpersonal set-up fits a tradition of essay films and ‘letter films’ reminiscent of Chantal Akerman and Chris Marker. Just like those OG’s, Van Nguyen understands that the intimate nature of her animation film, made of paper cuttings, should not stand in the way of taking on a broader scope. After all, the autobiographical can inspire an accusation against a system: “The personal is political.”

Van Nguyen’s father left her mother when she was pregnant with a daughter, after three miscarriages. Believing that his family tree would die without a son, he disappeared from their family life—a rejection that deeply touched Van Nguyen. Would everything be alright if she had been a boy? She dares to ask the question aloud, but without making it sound melancholic: in a short, flashy montage, we see a young Van Nguyen, now transformed into a young boy, happily spending time with her father. They race bumper cars through the desert, train together, and catch big fish in the river while cutesy 8-bit music seals the deal. The fantasy, however, is short-lived. Van Nguyen dismisses the thought when she (literally) tears it off and stuffs it into a ball of crumpled paper. She realises how the prison letters, in which her father writes lovingly but fails to mention his painful departure, smolder between the two like a great silence, keeping her from facing a bitter truth. While yearning to escape from the confines of the unspoken, her answer is as considerate as it is combative: “I understand that we grew up in two different worlds, but I don’t want to accept this part of your culture.”

Thus, a personal story becomes one of intergenerational and cultural confrontation (Van Nguyen grew up in the Czech Republic). Even so, the young filmmaker manages to keep her film, loaded with such hefty themes, surprisingly light, a feat she pulls off through playful formalistic experiments. The animated photo and text collages–some from Van Nguyen’s collection, some staged–make clever use of materiality that carries an inherent (pained) melancholy within but simultaneously lend the film a distinctive vibrancy. This scrapbook-like aesthetic, which invokes a quirky spirit of joie de vivre, causes an interesting friction with the aching family drama at hand. While the rapid passage of years is displayed via turning pages, we catch sight of a mature filmmaker, unafraid to tackle her trauma from different emotional angles. Always with a fresh dose of humor and without ever treading into the treacherous territory of navel-gazing.

So, when her father, after seeing the film, only asked questions about the impressive film techniques, we can only interpret it as his inability to express unspeakable grief rather than a failure on the film’s part. Yes, Van Nguyen’s formal proficiency is dizzying, to say the least, but it is never applied as a shield. On the contrary, the lack of ambiguity in her response is touching. If only all letters were this sincere.

This text was previously published in Dutch on Kortfilm.be.

There are no comments yet, be the first!