Bearing Witness

Handbook

While Handbook can be ruthless, Pavel Mozhar shows his finely-tuned sense for mutual respect even when the film is showing violently charged truths.

Handbook is a difficult watch. Naturally, one would expect such a statement describing a documentary which features torture scene reconstructions to bring attention to the physical dimensions of injustice against civilians. But is it more difficult to watch, than it is to imagine? Can an empathetic gaze account for the true horrors of systematic oppression and corporal punishments under a dictatorship regime? Film—as a recreation, rather than actual footage can only gesture to that which was, but by doing so, it presses a burden of responsibility down the spectator. The responsibility to bear witness to something you are not actually shown, which the filmmaker himself has not seen; events that have been mediated again and again before they reached the viewer. Since Pavel Mozhar decided to make the film after having watched numerous interviews of people who were brutally arrested by the special police forces on the August nights of the protests in Minsk, the first mediating factor is their oral testimony, then we have the actual recordings of it, and then the idea, the script before the short itself.

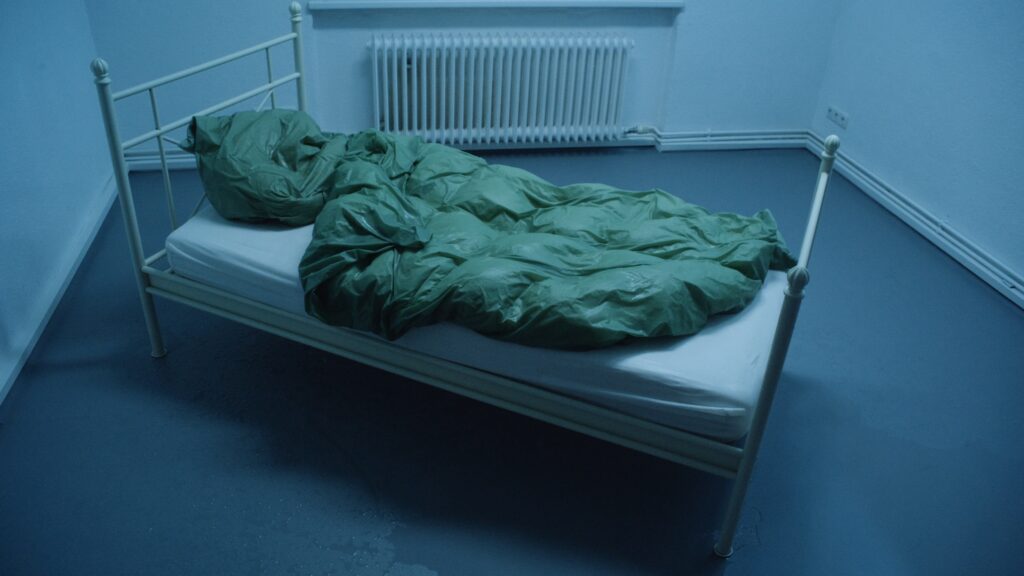

There is something to be said about degrees of removal here. As much as Handbook highlights the defamiliarization techniques often employed by documentary cinema by re-staging first person accounts of traumatising experiences in a rather performative way, it also tints them with nostalgia. The film opens with Mozhar’s own voice introducing us (in German) to his room in Neuköln, Berlin as a static shot captures its furnished interior, welcoming and warm. Five by four metres, sparse wooden furniture, some plants, and a work space–all the markers of inhabiting a place in a major European capital should be distinctively familiar. Until they are not.

On the desktop, drone shots of crowds light up the screen and the voiceover recounts what happened between 9th and 11th of August of 2020 in the Belarusian capital, Minsk, when the results of a clearly rigged election were announced; results that would keep Lukashenko in his presidency for almost three decades. The wave of protests that swept this silenced country empowered the special police (OMON) to take brutal action against the people who dared march against the regime. The image on the desktop is tiny in the frame of the still take, but the commotion is felt, heightened by the immobility of the camera and the fixity of mise-en-scene. The acousmatic voice recounts what happened in a sparse manner, with concise rhythm that enhances what toxic militance bleeds through the screen-within-the-screen as we witness videos of police brutality. In a way, the tone of voice also encompasses a certain desire to encapsulate an event that’s geographically distant but close to home–as in, to the home left behind.

Mozhar has grown up in Germany, he has formed himself as a filmmaker there and it’s only natural the voiceover is in German too. While this linguistic constraint acknowledges his degree of (physical) removal from the Belorusian protests, it allows him to make the film in a way that gets to the heart of what bearing witness through documentary cinema can mean: you and I are separate individuals, but never truly isolated. Other acousmatic voices appear as well, and they all speak Russian, their delivery flat and matter-of-fact as they narrate a catalogue of torture techniques, switch between objective account and the first person, to paint a terrifying picture of what went on behind closed doors in the few days of illegal arrests. It’s the very stake of a language shift which allows for a more intimate – and respectively, more disturbing–involvement as the film progresses. Part of the reason watching Handbook can be a challenge has to do with the way the film stretches its chronotope to infinitesimal longitudes and has to do with the way its pace conjures up the feeling that you’re walking through a tunnel that’s gradually shrinking. With this shrinking comes a metaphorical zoom-in on the pain of others, even if it’s both narrated and re-enacted in a distantiated way, an attentive look that refuses to look away. Here, uncompromising form meets uncompromising content.

Another peculiar approach Handbook undertakes in order to conflate distance and proximity has to do with its literal use of spatial dimensions. The aforementioned measurements of Mozhar’s Neuköln room is (5x4m) are later found in an animated sketch of a cell in a Belarusian detainee centre where tens of people were forced to cohabitate and sleep on top of each other. These animated interjections prompt our imagination even further while simultaneously opening our eyes to see the filmic space anew: the naked walls of the studio where the torture recreations take place is, in fact, Mozhar’s own Berlin home. This layering of spaces, imaginary and literal, also gestures to an attempt of witnessing, shared by him as a filmmaker directing all of this, and by us, as viewers.

There was one particular detail that moved me immensely and unexpectedly. In all the re-enactment scenes, one masked person would demonstrate how and where they would hit a victim, their touch filled with determination–a trace of the role they are inhabiting–and with retained gentleness, testifying to the fact that they are only acting. This tension between act and harm is embedded in any form of recreation and reveals the multiple facets of representation: the unattainable originary event, the interpretation of staging, the safeguarded repeated all exist concurrently. All of this is to be expected. However, what surprised me was how the breaking point of such well-constructed theatricality was also caught on camera. At the end of every such scene, the torturer would gently tap the victim on their shoulder and with this small gesture, this faint touch, all would exit the prescriptive act. In this detail, there is respite, there is care, there is hope. While Handbook can be ruthless (as it should be!), Pavel Mozhar shows his finely-tuned sense for mutual respect even when his film is showing violently charged truths. It is in the attempt to build a safe space where personal safety was brutally desecrated, where we can place our hope, even in the most hopeless of times.

There are no comments yet, be the first!