Big City Life

On Chantal Akerman’s Shorts

Chantal Akerman’s short films tell the story of a life engaged in an ever-changing relationship to the city, and to cinema.

No one has captured the emotional reality of big city life better than Chantal Akerman. There have been so-called city symphonies before in cinema, literature, and music—Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis by Walter Ruttmann, Quiet City by Aaron Copland, and Berlin Alexanderplatz by Alfred Döblin come to mind. Yet these focused on the city as a living organism rather than the individual experience of its inhabitants. Akerman created classics of the genre with the nighttime exploration of her hometown of Brussels in Toute une nuit (All Night Long, 1982), the visual postcards of New York collected in News From Home (1976), and the nocturnal wanderings of Paris, in Nuit et jour (Night and Day, 1991). Yet each time, Akerman alludes, either stylistically or thematically, to a more individual experience. Since a city can belong to nobody because it belongs to everybody, Akerman’s protagonists always inhabit the in-between, often merely passing through or waiting for something to happen: the not-yet. As outsiders, they enjoy the passive vantage point of onlookers, commenting on what happens around them, more often than not, through their bodies rather than words. It is in the positioning of bodies in relation to their surroundings that Akerman excels as a filmmaker.

The city is the locus of a kind of loneliness that differs from that experienced in the country. It is a loneliness made bearable in the act of waiting. Whereas in the country, one feels loneliness at being abandoned by the people one knows, like family or neighbours, in the city, our loneliness is that of the not-yet, born out of the people we have not yet met. Indeed, behind each corner lies the possibility of a future romance or the exhilarating opportunity of a life-changing friendship.

The four shorts I consider here, screened together in a programme titled “Blow Up My Time” during FeKK Ljubljana Short Film Festival this summer, all take place inside apartments located in the three cities that have defined Akerman’s life and served as characters in her films: Brussels, New York, and Paris. Taken in chronological order, they tell the story of a life engaged in an ever-changing relationship to the city, and to cinema.

First Stop: Saute ma ville (Blow Up My Town, 1968)

For those who encountered Akerman through her most famous work—Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, “The Greatest Film of all Time”—it might come as a surprise to find out how funny Akerman is in most of her other work. Saute ma ville, made when Akerman was only 18, is a Chaplinesque precursor to Jeanne. Here, the daughter tries on the housewife’s clothes with slapstick levels of pleasure. Coyly labelled as a ‘récit’, that French literary genre of a story with autobiographical undertones, it opens with Akerman coursing up the stairs of a building on the outskirts of the Belgian capital after collecting a letter in her mailbox. The young woman prepares a simple meal of pasta before undertaking mundane household chores in a progressively unhinged fashion. The editing is jarring, contributing to an atmosphere of mayhem, while in the soundtrack, Akerman hums and hisses along to her own shenanigans.

Saute ma ville (Blow Up My Town)

We experience this little burlesque through a handheld camera, which stays close to our protagonist, cramped in this small space. Even though we’re far from the carefully crafted shots that would determine her later career, Akerman already shows a keen awareness of composition. Twice, a cut is “hidden” by the camera closing in on Akerman’s body until the screen blacks out. A rapid shot of a balloon popping presages the eventual bang with which the film ends. The overall impression is a searching one, yet that does not mean any insecurity on behalf of Akerman. Rather, it expresses enthusiasm at the possibilities to be explored in the future. Her desire seems to blow up what seems too familiar and dive headfirst into the world.

Akerman would soon leave for New York by way of Israel. She was already too big for Belgium, and the Brussels of her youth. The world was calling out, and she would answer with a bang. Blow Up My Town is a statement of principles, a declaration of independence—a starting block for leaping forward towards even less conventional filmmaking. Nevertheless, the destruction with which the titular town is blown up seems, in retrospect, an eerily prediction of the tragic self-destruction that would close her body of work.

Second Stop: La chambre (The Room, 1972)

New York, the seventies: the city that never slept… and where a lot was happening in cinema. Akerman had seen Godard’s Pierrot le fou, and the Nouvelle Vague was taking over back in Europe. Godard and Duras had made the image self-conscious, aware of its artificiality. New York provided Akerman with the necessary distance from the motherland while allowing her to experience the avant-garde work of Andy Warhol, Michael Snow, and Jonas Mekas, in whose films she would later be glimpsed. Is there a movie more phallic than Warhol’s Empire (1964), emblematic of America’s obsession with itself? Of its promise towards and belief in the future?

Akerman soaked in all the formal and temporal experimentations. One recognizes Warhol’s influence in Jeanne Dielman, Mekas’ diaristic approach in her shorts, and the self-reflexive use of the camera one sees in Snow. And yet, by crossbreeding these formal approaches with the European self-consciousness the Nouvelle Vague exemplified, she would craft her own bastard cinema.

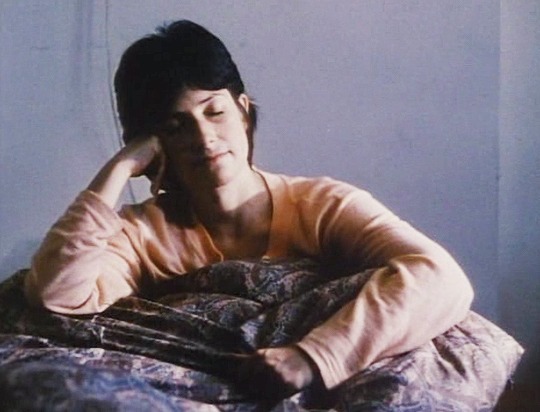

La chambre is a case in point: a formal study of the intimacy of her own apartment treated through the incessant circling motion of a camera. Akerman brought her own, arguably female, experience to formal experimentations. A 360-degree pan of the messiness of daily life that unveils the charming shabbiness of New York life. Once, then twice, the camera gives us a grand tour of this little room of freedom lost somewhere in the Big Apple. The city can only be guessed at, behind the blowout lighting that comes through the windows. The illusion of speed is created through repetition: the bed is empty at first but occupied the second time the camera pans around. The director lays across the bedding, eating an apple like a modern-day Eve. Akerman looks into the camera, at us, at herself. The images stare back, self-reflexively, taunting us, tempting us to project our ideas and prejudices on someone who is already so assured of who she is. Here is the space she first created for herself. In New York. By the camera. With this film.

La chambre shows us a woman who knows what she wants is out there, for the taking. Throughout her life, Akerman did not tire of relating how she funded this film (and her 1973 film Hotel Monterey): she worked the till of a gay porn theatre close to Times Square, giving each visitor a ticket, she pocketed half of the entrance fee and funnelled the money into her work. Making movies in New York was a matter of getting things done. She had travelled halfway across the world to find what she was looking for—the possibility of a new kind of image.

(La chambre) (The Room)

Third Stop: Portrait d’une paresseuse (Sloth, 1986)

City of light, city of love. Akerman wakes up again, this time in Paris. But she is no longer alone. In this new room, another woman is by her side. A lover, a friend? Presumably both. The privacy of an apartment and the intimacy shared within it. Staged glimpses of amorous bliss. While one is performing the music, the other completes it by listening, watching it come alive. What do we talk about when we talk about love? The less said, probably the better. Love is like silence; it vanishes when spoken of.

It is in love that most of the protagonists in Akerman’s find themselves, from Anna from Les rendez-vous d’Anna (The Meetings of Anna, 1978) to Simon in La captive (The Captive, 2000). Romantic love seems to offer the possibility of a sanctuary from the smothering of maternal love. At least, potentially. In Akerman’s work, the mother is a haunting figure, the accumulation of history, against whom the daughter reacts, often by fleeing into the city, into the night, into romance. The city where Jeanne Dielman goes grocery shopping during the day becomes the stage of fleeting moments of love between strangers at night. Akerman is amazing for the way she stages these meet-cutes: feelings spring from surroundings rather than being a conscious act. Portrait d’une paresseuse exemplifies this relationship between the staged and the real by showing us true intimacy as something staged.

Last stop: Le déménagement (Moving In, 1993)

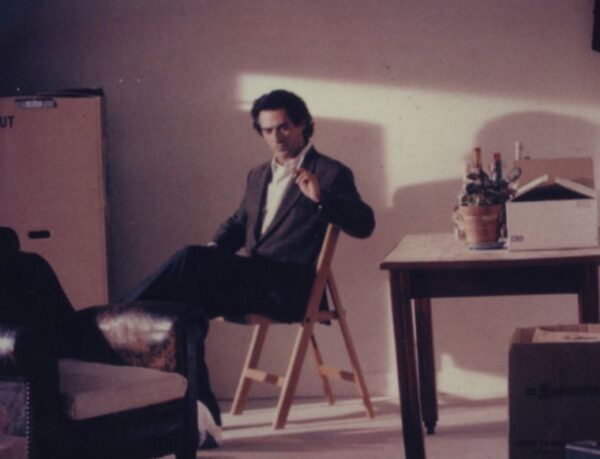

“There’s no soul in this place”: the first words spoken by a man as he walks into this new apartment, a new frame to be conquered. Boxes from a moving company are props in a melancholy monologue. Samy Fey is an exception in Akerman’s work. Indeed, he is not just any man but a stand-in, part of the band of outsiders that populate Akerman’s films. He walks in with a plastic bag with the words, “walking with his soul under his arm”. His moving in was not of his own choosing. He will tell us his story, like a confession, a recollection of happier times. Here is the story of three girls he met by accident—chance encounters. They had moved in first, in the apartment next to his. They were from Toulouse, not setting out together but finding each other in the big city because of their shared origin, as people sometimes do.

But Samy seems preoccupied less with other humans than with numbers. He tells us the apartment is “perfectly asymmetrical”, and to prove this, he walks the length and the width of the place. But his calculations prove to be wrong. He walks the length again, counting his steps; this time, the measurements fit with his theory. The apartment will disappear nonetheless, as the film consists of the illusion of a continuous shot zooming in on Samy and ending with an immediate close-up of his face; not unlike in Michael Snow’s Wavelength (1967), this measurement of slow movement runs parallel to the story of seduction. In a way, Samy is telling on himself, incredulous about the situation he finds himself in, striding across a vacant apartment that lacks a soul.

After all the wandering and explorations of different cities in the two preceding decades, Le démenagement feels like a moment to take stock. The slow, pensive zoom, a rarity in Akerman’s work, becomes meditative in combination with the tale of love and loss Samy tells. It is no coincidence that Akerman would reinvent herself as a travelling documentarian and installation artist in the next decade. The whole of Akerman’s oeuvre is characterised by a sense of restlessness that sees protagonists keep on moving, no matter what.

Mentioned Films

Saute ma ville

by Chantal Akerman, Belgium, 1968, 13’

A young woman, played by Chantal Akerman herself, enters her kitchen and begins a gradually degenerating household routine. Parodying the everyday, she mops the floor, polishes her shoes, sticks tape over the cracks of the door and gives an explosive twist to domestic life in a Brussels flat.

La Chambre

by Chantal Akerman, Belgium, 1972, 11’

Panning shots describe the space of a room as a succession of still lives: a chair, some fruit on a table, a collection of solitary, waiting objects. Sitting on the bed there is the presence of a young woman: the filmmaker herself, eating an apple.

Portrait d’une paresseuse

by Chantal Akerman, Belgium, 1986, 14’

In an exercise of ironic self-awareness, Chantal Akerman tries to cope with her tendency to procrastination and laziness by making a film about laziness itself.

Le Déménagement

by Chantal Akerman, Belgium, 1993, 42’

The man in his new home, unable to unpack the many boxes and crates that surround him. His soliloquy is one of indecision, of regret, of a sense of predicament that is inescapable. Through this protagonist, Akerman reflects on the impossibility of making decisions, of the forlorn hope of certainty.