Blind Date

First Sight

Andrew McGee anchors his sci-fi story in an AI-dominated future, twirling around romance, horror, thriller, and a slice of comedy.

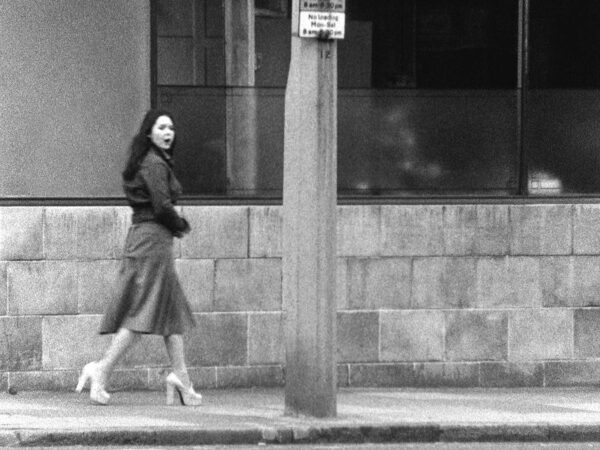

First Sight, an AI-powered dating extension for smart contact lenses, seems to promise a remedy for dating anxiety. Luna, the protagonist of British director Andrew McGee’s latest sci-fi short, aptly named First Sight, isn’t initially sold on the idea. Intuitively swiping away an intrusive pop-up ad while browsing the video library of her late partner through smart lenses, she hesitates when the ad reappears, tempting her with the words, “Begin a new story today.” As Luna battles with her anxiety about re-entering the dating world even when matched with someone with a 97% compatibility score, Anthony, the “fix”—an ad for a free upgrade to a more advanced model of smart vision technology, Optic Lens 2—arrives at the perfect moment. With her decision, the melancholic setup of First Sight unfolds into a twisting tale of how technology can prey on human vulnerability.

At the start, the upgraded smart lenses guide Luna through the scenario of a perfect date—calming her nerves, safe-checking her date, and pulling out information on Anthony’s reading habits. At the same time, she also seems to retain enough agency to lead the conversations with what she calls “creative control.” When the pair’s casual conversation shifts towards critiques of AI-enhanced products, Luna wittily manages Anthony’s suspicion about the smart lenses since the topic falls right under her profession as a tech journalist. While audiences may already be familiar with the first-person viewpoint of First Sight’s AR interfaces from dystopian tech-themed stories such as the Black Mirror series, McGee and his team take an innovative turn by showing how visually wrong things can go.

Not long after, the viral pop-up window disguised in its sleek design reminds Luna—and us—that every sweet free trial ends. The smart lenses malfunction and the film image cracks, as does Luna’s illusion of creative control. When she excuses herself to go to the bathroom, the story ventures into the dark and stormy, just like her drink choice for Anthony. Seeing that the subscription needs ten thousand dollars, Luna knows she has been scammed. With the threat “I have your eyes” followed up with the command “send $10,000m” popping up on the screen, it becomes apparent that forcibly taking off the lenses is not the way to go. “You look gorgeous,” Luna compliments back to another woman, resisting the instruction to say the opposite. This little act of defiance comes indeed at the cost of her vision. The perfect date slides into a literal blind date.

McGee’s depiction of the fractured vision reconfigures the narrative from a futuristic romance into a haunting horror. The audience sees through Luna’s eyes; with her surroundings melting into a smudged blur, we are synchronised with the experiences of dread and desperation. The cut to a deserted hospital hall evokes the atmosphere of a first-person horror game; this association could be intentional, given Luna’s earlier accounts of using smart lenses casually for playing games. In his earlier Blade Runner-esque cyberpunk short, Venues (2022), McGee has already experimented with glitchy and pixelated aesthetics to depict the process of vanishing within a virtual world, exploring the relationship between kinship and mortality. First Sight builds on this approach, anchoring it in a reality-driven world in the near future. While AI-enhanced tools are becoming so pervasive today that arguably they no longer can be easily pinned down in the realm of sci-fi, McGee and his team manage to graft sci-fi elements with body horror by visualising Luna’s own fractured agency. Thankfully, this unsettling scenario still remains fictional.

Instead of following the all-too-familiar “evil technology” trope, First Sight delves into depth and complexity: underneath the sleek design of a technological tool lies the exploitative logic of corporate power. First Sight probes into the ethics of using technology by juxtaposing the blackmailer’s gamified, almost playful means with Luna’s range of responses, from fear to anger to despair. Her changeover from hesitant optimist to exploited victim is synthesised through McGee’s precise editing work. In addition, Ellise Chappell’s evocative performance as Luna, especially in a bathroom scene where it’s as if she has been possessed, stretching those few on-screen minutes into eternity. We empathise with Luna not only because we are temporarily immersed in her distressing world both physically and psychologically but also because we recognise how our personal insecurities, our processes of grieving and healing, can be conveniently commodified, making us the target crowd for a product, a service, a brand, a subscription, delivered to us based on some algorithmic calculation in the form of a pop-up window, awaiting a mindless click.

When Luna throws her phone off the building, the phrase “connection lost” appears on the screen over the skyline. What might conventionally serve as a cue for a thriller twist becomes Luna’s silver lining of her disconcerting night. She returns to Anthony. Under the dim yellow light, their conversation restarts, with Luna covering up the incident, “That’s just a trial period.” Funded through a successful Kickstarter campaign—proving the film’s topical relevance shared by an extending audience base—First Sight offers a well-rounded story within its limited scope, with a well-balanced script twirling around romance, horror, thriller, and a slice of comedy. The film evidences the director’s humanistic touch to the ubiquitous theme of techno-ambivalence in our datafied society. With a passion for diverse sci-fi subgenres, First Sight might be just a tease of McGee’s competence in fleshing out the narrative possibilities in the cinematic digital imagery per se.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #6—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!