Daddy Issues

Lemon Tree

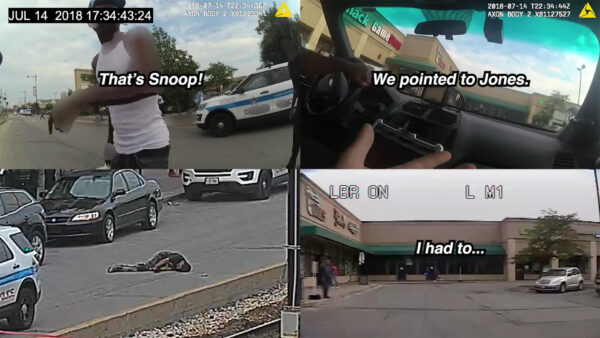

A father takes his son to the funfair on Halloween. What should be the stuff of childhood dreams becomes, instead, the therapy material of adolescent trauma in Rachel Walden’s gut-punch roadtrip.

White rabbit: that glorious Janus-faced symbol of drug use and good luck, of spiritual rebirth and boyhood innocence. In one short film, the world spins around a scruffy-faced father and his ten-year-old son faster than the rides at a New York amusement park: a swig of glass-bottled Coke, a plushie won, a go on a Tilt-a-Whirl knockoff, Halloween masks worn at funhouse mirrors. “Give me the money, win the bunny!” shouts a carnival worker. So, on that fateful October day, Dad steals the white rabbit from a carnie who takes a jab at the duo, the poor fluffy thing-in-a-crate a prize for a rigged game nobody will ever win.

This is Lemon Tree, NYC-based writer-director Rachel Walden’s semiotic playground laden with a sense of inevitable devastation. Based on a story gleaned from the filmmaker’s grandfather, the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight pick played in the Sour Maturity block of the Vilnius Short Film Festival’s International Competition. Opening and closing with the uneasy twang of a jaw harp, the film’s most notable feature is that it screams indie neo-Americana. From the clothing (the boy’s Apollo 11 vest and the father’s Honda bomber jacket) down to the repurposed Altoids mints box (the pinnacle of lazy-man’s recycling), it’s a bold aesthetic evocation of 90s independent U.S. filmmaking, otherwise not so subtly suggested by the short’s alt-rock soundtrack that buzzes with thickly modulated guitar.

After running away with the rabbit, the father-son duo stop at a series of small-town upstate destinations. First, Dad pops into a roadside shop, where he buys the boy a gag lottery ticket (he “wins” 5000 dollars). Then, they make a pit stop at a fruit stand, purportedly to get a “sweet treat” for Mom (only for Dad to chat up the woman selling fruit). Finally, they pause at a diner—but Dad leaves his son to fend for himself at the table (once he returns, it’s later clear he was getting loaded in the bathroom). As they roar down Route 9, for a moment—a heartbeat—all might be well. But the stolen rabbit, the fake lottery ticket, the fruit stand lady, and the lonely diner are all fabrications of honest, beautiful, unforgettable childhood moments. They’re modular encounters dripping with Dad’s solipsistic thoughts draped in a robe of paternal altruism.

With his father, the boy is “boss”, “buddy”, and “little man”—conventionally adoring pet names whose empty gestures reduce him to namelessness. But his son’s eyes mediate the story of Lemon Tree, carrying the weight of the world within them, as exemplified through a scene at the film’s halfway point. At the fruit stand, Dad begins to flirt with the saleslady. The boy watches blank-faced and wide-eyed from the backseat, waiting for the interaction to unfold: Does he need to take action or simply play his part? Then, with the camera tracing the boy’s POV, Dad brings the woman to the car to see the rabbit—or rather, to whisper in her ear and touch the small of her back.

The woman leans in to pet the animal, her breasts nearing the boy’s face under her Daisy Duck-adorned tie-dye shirt. But the childish, or childlike, iconography is spoiled by the moment, just like all the rest. Dad, now the sickly sweet philanderer, makes up a tale about winning the rabbit “fair and square”. He even imposes a name on it: Melon (no doubt he’s thinking deeply about the breasts). The camera closes in on their faces, and the film cuts between the four visages; the bunny, too, wiggles its nose warily. And so the boy shrinks inwards and closes his eyes, his eyebrows crinkling in discomfort at being forced down the rabbit hole of adulthood.

This should be the time of his life when hedonism encouraged by a parent is a privilege and when you’re absolved of responsibilities and can tumble forward freely with Dad spotting your trust fall. Scenes between the two are carried out with tight handheld visuals, the slight shakiness betraying the fragility of the present moment. Everything is too close and too fast for comfort; the boy cannot escape. And the father is well on his way to deadbeat dad, a veritable Mister Americana of the real world.

After the boy wakes his father from a stoned-out stupor in a gas station parking lot, they’re quickly resigned to what is undoubtedly their usual role reversal. A slap to Dad’s face and a cup of water poured on his head (he plays it off with a neutral “thank you”) dissipates the sparkling fantasy of the earlier hours. By the nonchalance of it all and by the way the young boy drives them both carefully home on the dark and rainy highway (with Dad sleeping soundly in the backseat), it’s clear this isn’t his first rodeo. Looking back at his father, peacefully cuddling with the rabbit, the boy rubs his eyes. There still aren’t any rose-colored glasses strong enough to tint this moment in a positive light.

Even the closing scene’s decisive interaction between father and son is nothing but another disappointment in a long line of lies disguised as parental generosity and a faux shield from the cold, cruel world. The boy speaks out loud only in the final few moments of the film, only when there is life to lose. His last resort is to call for his father, his parent, and his not-so-guardian. Will somebody come to his aid? If he can just find the rabbit in the car and take it home safe and sound, care for it, treasure it, and nurture it, then maybe all will be well.

But nobody comes. Deceit reveals itself in closely framed, out-of-focus movements, where the father seems to even be hiding from the eye of the camera itself. The bunny, the lottos, and the rainy evening are all symbolically endowed signs of a boy’s life tarnished. And yet, at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter. What should be the stuff of childhood dreams is instead the therapy material of adolescent trauma, semiotics be damned. It’s a gut-punch roadtrip.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #3—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

Nice text!