Digital Romanticism

Interview with Samira Elagoz & Z Walsh

In You can’t get what you want but you can get me, a slideshow of screenshots and photographs depicts how filmmakers Samira Elagoz and Z Walsh fall madly in love. In this interview, the artists discuss their teenage-esque love story, virtual foreplay, and the hypersexualisation of trans* people in media.

The text message “The two long-haired trans guys alive rly should meet” is the opening shot of You can’t get what you want but you can get me, accompanied by the instrumental beats of The Strokes’ The Adults Are Talking. When the vocals come in, candid shots of filmmakers Samira Elagoz and Z Walsh appear in the frame, the first of many intimate photographs that make up the structure of this short, chronicling their relationship. The film is divided into three chapters, each accompanied by its own song (The Strokes are followed by Alex Cameron and Beach House), which serves to underscore the emotion conveyed through photos and screenshots of text messages.

The project is a collaboration on every level—both filmmakers have separate artistic practices that inform the film: Walsh’s photographic expertise and Elagoz’s specific approach as a documentarian, in which he is as much a part of his films as his subjects are. In this way, the gaze works in both directions, as two people portray and, more importantly, truly see each other.

Cinematic portrayals of trans masculinities are few and far between; even rarer are ones that aren’t censored for a cis audience or concerned with explanations. You can’t get what you want but you can get me doesn’t offer any, but it almost casually does offer astute commentary on present-day masculinity. Elagoz’s and Walsh’s thoughts on trans portrayals and masculinity are thoughtful and nuanced, combating regressive and often uninspired cis narratives of what it means to be a man.

The fact that I conducted this interview via written correspondence is fitting for a film that highlights the romanticism of digital communication and relies on text messages instead of spoken language to communicate feelings. It also feels very satisfying to watch a film that successfully translates a key component of its premise into the structure. The use of the term “modern love story” can feel trite, but this actually is one. The portrayal of yearning and intimacy manages to be earnest and horny at the same time, maybe because there is an underlying vulnerability to the project, without which it’s impossible to be either of those things.

Your short has an almost casual quality because of its slide–show format, but of course, that’s only possible because you were very precise in your selection and editing process. When you decided to make this film, did you already have some of the photographic material to pair with the messages, or did you shoot some of the photos specifically for this purpose?

S: Both Z and I have made careers of going into strangers’ homes with our cameras—Z photographing them and me filming them. My whole body of work is about meeting strangers and making work about the encounter. But with Z, it was different. For the first time, I was meeting someone I found interesting without the intention of filming them. But then Z started taking photos of me on the first date, and it kind of rolled on naturally: we kept on documenting each other and ourselves falling in love. We never planned to work together; we just started filming each other. Only months later did we realise that this could become a project. So, the love came first, then the work.

Z: When I first met Sam, I knew I was gonna fall for him. Desperate to remember every detail of that day together, I started taking photos of us with my point-and-shoot [camera], and I just never really stopped. At the time, I didn’t know that a big part of Sam’s work revolves around filming first encounters. I imagine he was just as excited as I was to finally meet someone else who also wanted to document our shared experiences. We were both so used to being the one with the camera, but in our dynamic, no one’s gaze was lost.

Why did you choose the format of the slide show for this project, and how does it inform this specific story you’re telling?

Z: Sam comes from film and theatre, and my background is in photography, so in typical long-distance relationship style, we met in the middle. As a photographer, there are certain images I get really attached to, but thinking so literally about narrative was new for me. I was impressed watching Sam build his selections around storytelling. The way he edited made the imagery I was attached to pop even more.

S: Moving images allow more space to tell a story and create a dramaturgy, so it was a challenge to edit a storyline that relies solely on still images to convey a narrative. It almost felt like every photograph was a film scene on its own. As if they each needed to build upon the previous one or bring something that we haven’t seen yet. Like an endless climax loop. I’ve likened the editing process to stand-up comedy, where you need to make your audience laugh every ten seconds or you’re out.

You can’t get what you want but you can get me (Samira Elagoz & Z Walsh, 2024)

You both are, of course, very present in the film. Still, we never hear you speak—instead, we see you or your texts, which allow the viewer intimate glances into your communication but also leave room for interpretation. As someone who texts a lot, this felt very familiar to me. What are the reasons behind this choice, and what can text transport that spoken language maybe can’t?

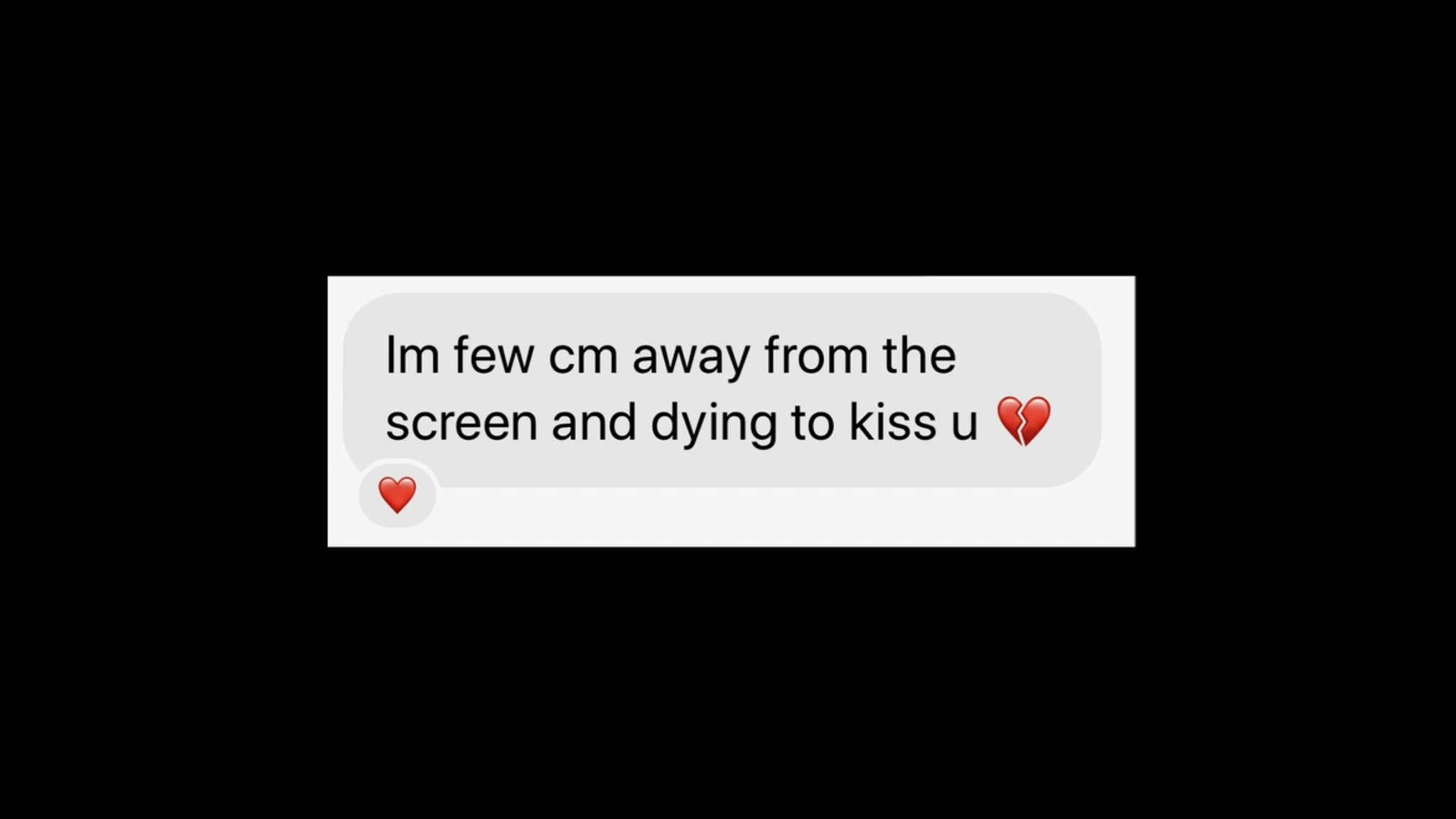

S: From an editing point of view, it was the glue that held the narrative for our photographs, but I’ve always been a digital romanticist, and find seduction through texts and DMs highly attractive. There is an inherent fetishisation [that goes] into crafting a good message. Choosing the right words to say or withhold is romantic foreplay and its own kind of poetry. Communication through text leaves a lot to interpretation, and it functions in the same way in our film. There is one screenshot in the film that shows a notification of Z having sent me 57 messages. That image alone pretty effectively conveys the sentiment of a crush.

Z: From the first messages, there was always a heat between us over text, and as our relationship deepened, it became crucial to stay connected there when we were so far apart. Like many couples, we made up our own little language, but being long-distance meant we had to write ours down. With the film, we ended up communicating with the audience in one of the ways we communicate with each other.

The songs you used are memorable and feel very important to the emotionality you’re conveying with each of the film’s chapters. How did you decide which songs you would use?

S: I always say that fanboyism is the sixth love language. At the beginning of our relationship, we bonded over music, and I think I fell for Z when I realised he was also a fanboy. In the past, I’ve interacted with many fanboys, but they rarely cared about what I liked. With Z, it was different; his excitement for sharing culture felt hyper-romantic. We’d send each other photos of long-haired rock stars in the same way people send cat pics to each other and say, “This is us.”

Z: We only used songs we were listening to while we were falling in love. We’d lie in bed together for hours, sharing music we’d collected that we thought the other would like. One song in the film is one I’ve used as a kind of litmus test because most people I’ve played it for don’t like it, so of course I was really excited that Sam did.

Watching your film made me think of Anne Cvetkovich’s work on queer archives, where she argues for understanding them as archives of emotion, containing artefacts that often aren’t part of institutional or mainstream archives, and preserving evidence of queer lives. How does the notion of archiving or documenting connect to your work, in general, but also specifically related to this film?

Z: The absence of trans people in art and media isn’t accidental. Ongoing systems erase, ignore, and flatten our lives. As trans men, we face near-complete erasure of our history and existence while sporadically portrayed in cis culture as lonely, detached side characters.

Our work showcases a genuine gay trans relationship. Through archiving queer transmasculinity, we offer a vital public record of transgender life. Our urgency is to build a reference point for T4T (trans-for-trans, ed.) love, moving beyond the usual tropes of trauma and tragedy, or the sanitised, overly wholesome portrayals neatly packaged for cisgender consumption. We’re preserving something tangible for each other and for the ones who come after us.

I really liked how explicitly sexual your film is because so often trans sexualities and desires are either erased or oversexualised from a cis perspective. It’s also so rare to see a depiction of desire, particularly in a T4T relationship. How did you figure out what you’re willing to share and what you wanted to keep to yourselves?

Z: That’s funny because at our very first Q&A after the premiere at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, someone asked why we chose not to include us having sex in the film. Trans people in media are hypersexualised for the pleasure of cis audiences, and at the same time, our real desires are erased. The only way to combat this misrepresentation is to tell our own stories, with all their complexities and beauty. That’s also one of the reasons we think it’s important to show real intimacy, not staged.

S: There is something very innocent about the film. It captures an almost teenage-esque love story. I think the real eroticism of the film comes from the insatiable yearning. Also, creating together became kind of erotic. Not in the sexual sense per se, but in being alive and excited. Being part of any revolutionary movement feels erotic, too. Again, not necessarily in a sexual way, but it has a lot to do with transgressive force, liveliness, and breaking rules.

You can’t get what you want but you can get me (Samira Elagoz & Z Walsh, 2024)

It feels precious to see such a vulnerable and playful depiction of masculinity. In one of the text messages, you describe each other as the peak or literal definition of masculinity. What does the term “masculinity” mean to you?

Z: I notice that trans people are not afforded the same creativity in our gender expression as our cis colleagues, even though transness is based almost entirely on self-creation. For me, it’s not that I’d simply like to be recognised as “a boy.” I’ve always thought the hottest boys are the ones with long hair and tight clothes, who aren’t afraid of a little makeup, so naturally, this is the kind of boy I want to be. Finding Sam was a game changer because he not only embraced my gender expression, but actually understood it. I had never met anyone who expressed themselves so similarly, and we were inspired and emboldened by each other. Our brand of masculinity is my favourite, but there are a lot of other good ones out there, too.

S: I have filmed men, cis and trans, for over ten years. There is a seemingly unresolvable crisis of traditional masculinity. Cis men are usually bad examples of masculinity; they’ll appear a bit hopeless or ridiculous and unwilling to progress, so as a transmasculine, I feel the burden is on us to be better while their crisis awaits its revolution. But what even is credible masculinity anymore? There is certainly no good role model of masculinity. I’ve found transmasculines are not immune to toxic masculinity. It’s actually easy, dare I say tempting, to adopt that role, which can feel almost like a caricature when you do. When one is expected to “pass”, the most direct route is to perform cliched tropes. At its best, trans masculinity can envision the future of masculinity. And at its worst, it mimics its failings.

There is a violent and complicated history with regards to how trans people and specifically trans bodies are portrayed in film, often from a voyeuristic cis perspective. Your project very clearly combats these narratives, not just because you are trans but because of the care with which these images are shot and arranged. Is there, in that sense, a trans gaze, and what does it look like to you?

S: My work has always been concerned with dissecting and defining the various gazes. The thing about the male gaze is that, at its core, it is boring: cis men projecting lascivious fantasies onto women. I’ve been filming strangers my whole career, and I never had the intent of ascribing them to a specific role. I always knew I didn’t want to make traditional documentaries. I believe it’s rather cowardly to just stay behind the camera, to not put yourself on the line. My subjects could show themselves to me as they wanted to be seen. I gave them the freedom to use the camera, to turn it around on me. But to be frank, I’m not so invested in the gender of a gaze anymore. A curious gaze should not be tied to the maker’s gender, but to the way they choose to make work.

Our film is about love, and for anyone who’s ever tried to understand themselves through another. I think the work succeeded precisely because it has managed to touch such a variety of people. Someone in the audience called our film “an unapologetic T4T story that is not concerned with explaining itself for the cisheteronormative gaze.” That’s exactly what we wanted to make: work that is less focused on our gender identities and more on the connection we have with each other.