Emptied Away

The Veiled City

Natalie Cubides-Brady’s sci-fi city symphony is reminiscent of Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962).

Being exposed to archival footage, peering into humanity’s past through still or moving images may sometimes feel akin to digging into the Earth, whereas the footage we encounter is often bound to be seen and understood at face value: that is, through the lens of its current form rather than what it used to be. Indeed, most archives we get our hands on are rarely more than mere fragments, shells of a distant life, whispers of a bygone era. It’s like lifting a rock out of the ground. We may theoretically understand that this small piece of sediment once was a majestic boulder the size of a house, but in reality, it’s surprisingly hard to conceptualise matter (in this case, a rock) any other way than what is lying before our very eyes, right here, right now.

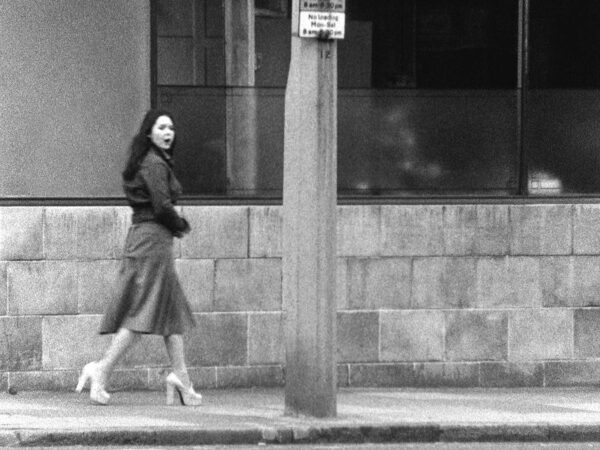

Because of its partial nature, especially as we dive further into the past, archival footage also has an innate tendency to create distance between the audience and the filmed subject matter. Look into the eyes of a man crossing a street in black-and-white 1950s London and try to picture him being sad, angry, or overflowing with joy. It’s certainly possible, but hard without a conscious effort from the viewer to connect with such a distant character. Indeed, human empathy, as complex as it is a strong phenomenon, needs a plethora of stimuli (movements, colours, sounds, even smells) to enable a sense of identification with someone we encounter and to allow ourselves to recognize that they are, in fact, “one of us”. One has to watch colourized and remastered ‘street scenes’ of early 20th-century cities, widely available online, to acknowledge how our empathy grows exponentially stronger with every stimulus added to our viewing experience (colours and sounds, for example). On the other hand, of course, by removing some of the aforementioned stimuli, our ability to empathise with one another drops significantly, and that is partly what British-Colombian filmmaker Natalie Cubides-Brady has opted to do with ‘The Veiled City’.

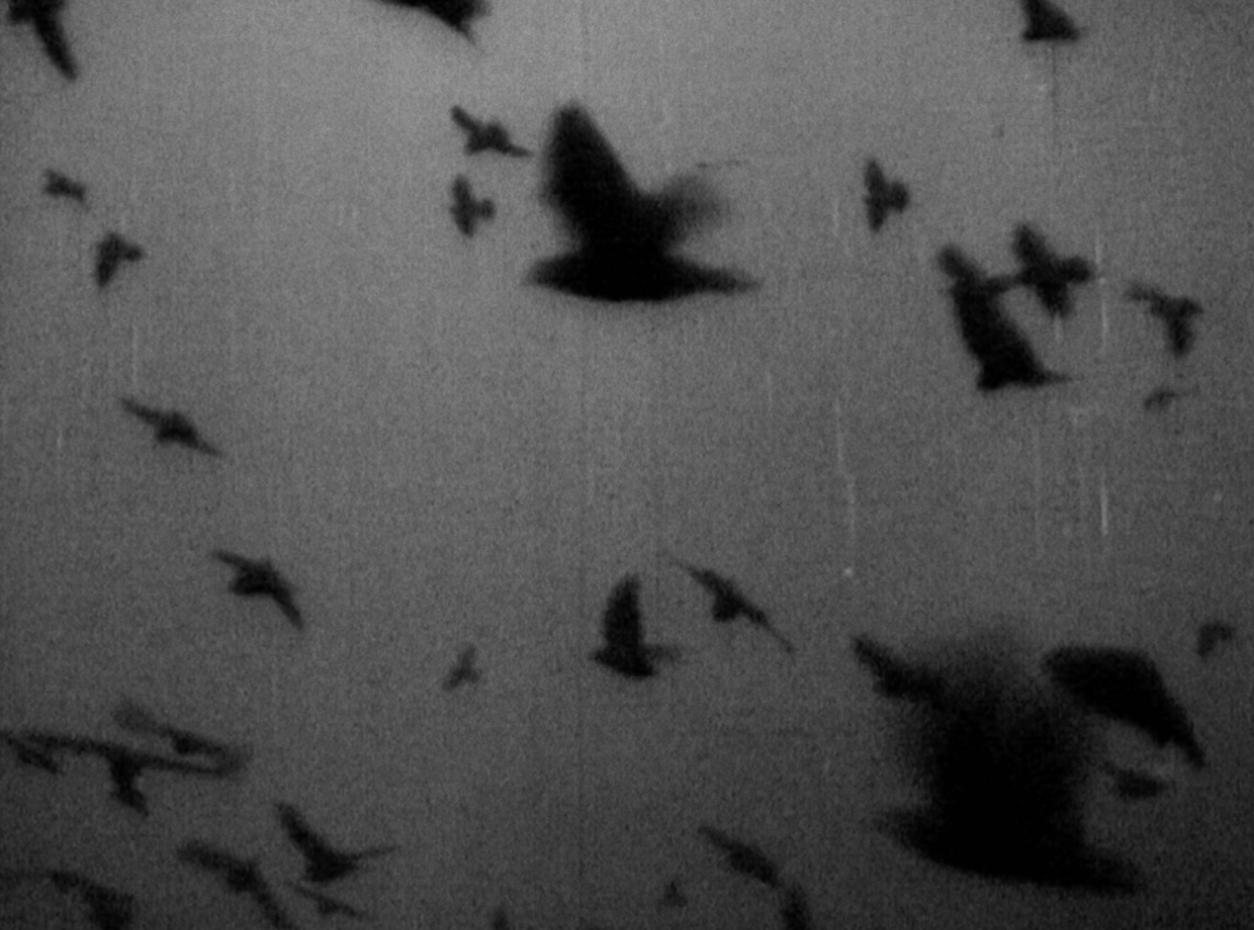

Sitting at the intersection of documentary and fiction, her most recent film allowed her to work entirely with archival footage of London to create an ecological cautionary tale. Shot during the Great Smog of 1952, the fragments of films she uses, showing streets, parks, metro stations, and various urban landscapes, are edited in such a way that the viewer never really gets a chance to connect in any way, shape or form with the many silhouetted characters portrayed onscreen. Rather, the heavily degraded nature of the footage, the overwhelming presence of coal-induced smog, the high contrasts, and the many industrial buildings casting big dark shadows over the camera all convey a dreamlike, otherworldly view of this event. Instead of trying to counteract these side effects, Cubides-Brady decides to embrace the images’ imperfect nature to create a lasting emotional response. Indeed, as an unknown voice-over recites fictional letters from a post-apocalyptic future, claiming she managed to travel back in time to investigate the origins of what seems like humanity’s extinction, the barren streets of smog-covered London appear so dramatically alien to our modern eyes: it’s as if it never really belonged to our universe. Even if we all know it undeniably did.

Rather obviously inspired by the work of Chris Marker and his genre-defining short ‘La Jetée’, ‘The Veiled City’ is an intimate and poetic look at a decaying world where images of the past are used as a warning sign to tell a futuristic story of what is to come, blending both timelines in a surreal and — for lack of a better word — brutalist way. One of the many parallels to be drawn between this film and Marker’s magnum opus is that both protagonists show a visceral desire to hang on to their most beloved memories throughout their quest, as if their lives literally depend on it. Perhaps their shared obsession with the past allows them to defy death in some way. After all, is there a more powerful tool than nostalgia to fight entropy? Or, perhaps their memories’ purpose goes even further. When Cubides-Brady’s narrator constantly evokes past conversations she had with her sister — a certain ‘Ida’ who fell ill in the future and died of complications due to the poisonous air which has engulfed the Earth’s atmosphere in 2198 — these bursts of nostalgia, similar to those in ‘La Jetée’, recorded and transmitted into the void, act as a literal bridge between past and future times. As if the memories themselves were the vessels that allowed the protagonist to time travel or, at least, to communicate through this dimension, which suggests that her ability to remember – more than anything else – made her worthy of such a mission.

Furthermore, it’s striking how the letters, the film’s sole narrative threads, are all recited in a notably solemn tone. This hints at the fact that the narrator suspects there’s no one on the receiving end of her messages and that she’s at least trying to be at peace with this soul-crushing reality. Besides, since her sister Ida is never really defined as a character, other than that she’s an ageless victim of some unclear climate apocalypse at the end of the 22nd century, this can be understood as her being a placeholder for the audience. When the narrator dramatically asserts the following statement: “Dearest sister, you will die like this in the future,” it’s a hint to who she’s really speaking to, and even more so when she maintains that most, if not all, deaths caused by this thick veil of smoke won’t leave much of a footprint in Humans’ history other than being converted in mere numbers in some government report. Indeed, that last bit will most certainly ring a familiar bell in the modern viewer’s mind.

Finally, as she goes on describing her lonely attempts at discovering the true source of her people’s eventual demise, travelling in and around the suffocating metropolis; her words and her whole existence, like all the silent silhouettes we encounter, slowly disappear, disintegrating, into the mist. In the end, the more she engulfs herself in the dark clouds descending upon the city, the more the audience is led to realise that her mission to find and disrupt the beginning of the end, the birth of the Anthropocene, never really had what it takes to be anywhere near what could be described as a ‘victory’. After all, since waking up next to dearest Ida’s cold body right before she travelled back in time, the grieving protagonist may have decided that such an objective wasn’t even worth it anyway. The best she could do, then, was perhaps to use her few last breaths to simply document, to describe, and to do what she does best: to remember.

There are no comments yet, be the first!