Emulsion and Emotion

Analogue Film In The 2000s

During its 65th edition, Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen focused on analogue film material and its importance in the digital age.

On April 4, 1986, reactor unit 4 of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant exploded. Three days later, filmmaker Vladimir Shevchenko flew by helicopter over the accident scene and accompanied the first decontamination efforts on site. When Shevchenko later developed the 35mm film material, he noticed that parts had white spots that looked like short flashes of light when projected, and the soundtrack contained disturbing static noises. He and his team initially assumed that the raw film material was defective until it became clear that the film had reacted to the radioactivity. In Chernobyl – Chronicle of Difficult Weeks (1987), you can see and hear the deadly radiation. Shevchenko spent a quarter of a year filming in the immediate vicinity of the damaged nuclear power plant. He experienced the premiere of his film in Kyiv in 1987. Shortly afterwards, the director died in a hospital for radiation patients.

The fact that not only photography or film, but also the film material itself is like a skin, i.e. possesses something living, almost human, has already been pointed out several times in film and photography theory. Chernobyl – Chronicle of Difficult Weeks makes this analogy cruelly clear when the contaminated film material, which exhibits symptoms of radiation sickness, anticipates the death of the director. And perhaps it is this brittleness—which seems to prove liveliness and thus transience—that continues to fascinate us and not only keeps our interest in celluloid film awake, but has allowed it to grow again in recent years. In recent times, for example, around fourty self-directed artists’ laboratories worldwide have founded and networked on filmlabs.org to advocate a new practice of collective organisation of means of production for artists and filmmakers working with film and to keep photochemical knowledge, communication and technology alive. For the second time, some of these labs presented a selection of their film works at the Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen, which this year focused on analogue film.

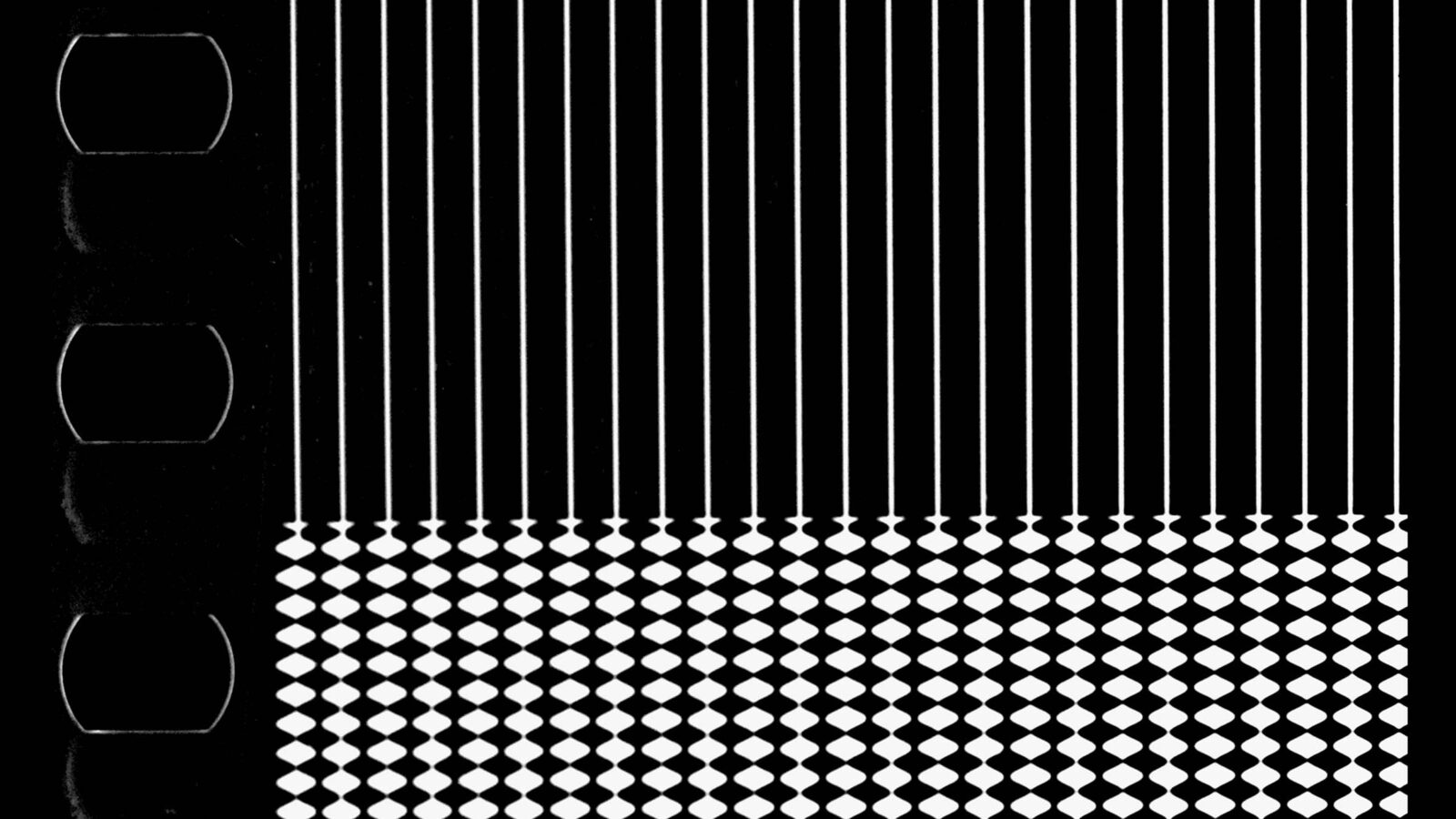

The fact that a young generation of female directors, most of whom came to filmmaking in the digital age and now turn to celluloid after exploring this smooth and high-resolution world, has been observable for some time now and was repeatedly highlighted in Oberhausen in the moderations according to the overriding theme. The competitions featured Dianne Barrie and Richard Tuohy’s China not China (2018), Stefano Canapa’s The Sound Drifts (2019), Roger Horn’s Scenes from a Transient Home (2019), Melisa Aller’s Caída (2019), James Edmonds’ A Return and Richard Reeves’ TV (2018)—works in which film material was edited directly or which were shot on film and in some cases also shown on 16mm or 35mm and which revealed the specific characteristics of the celluloid or the technical apparatus.

The eight programmes offered classics and alienations and showed rudimentary developments and peculiarities: the integration of shots of the shooting, minute-long speeches by producers, witty directors, or deliberate provocations. Including more recent trailers, which could have proved a comparison or further development, was missing, as was a comprehensive, global view of the phenomenon. Even the curators Cassie Blake and Mark Toscano could not adequately justify the limited view of American cinema at the audience’s request. Damon Packard’s persiflages on the trash cinema of the 80s were tiresome in their redundancy. The significance of the section, its scope, and its content then increasingly diverged with each new programme. The Best of May (1972), a compilation of bomb drops during the Vietnam War—which must have shocked the audience at the Ann Arbor Film Festival, where the trailer was first shown as an activist gesture—will be remembered. In addition, it is the traces of wear and tear on the trailers that are remembered because these visible testimonies to transience no longer exist in the cinema, and they once again refer to the short life of the trailer as a pure advertising medium and recall the vital work of archiving and restoration.

What can make working with film material so unique is conveyed in Oberhausen through a selection of the work of Japanese artist and filmmaker Kayako Oki, which was shown for the first time in Europe. The studied textile designer traces the materiality of the narrow film material in her cinematic works, cuts, and sticks as if her films were made for wearing on the skin. They are delicate experimental colour rushes and meditations that lovingly depict the film creation process and self-confidently carry their transience within them. Especially in her work, it becomes tangible what the loss of analogue film material would actually mean: without celluloid film, certain films would simply not exist. And without celluloid film, they will no longer exist in the future.

Beyond all the nostalgic feelings that filmmakers like Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino associate with celluloid and beyond the haptic experience on the film set and in the editing room, which have a direct effect on the handling of film and its creation, the loss of the carrier material film means the loss of the possibilities to work and experiment with the material. The use of chemicals, fading in the sun, scratching, destroying, gluing over, the production of own emulsions, multiple exposures, photograms, and all the coincidental effects that produce the unplannable with itself and unique films—none of this could still be done.

Digital cinema knows no experiments of this kind and no process; it only knows the low-complexity duo 0 and 1 as present and absent, as on and off, which is always controllable and therefore calculable through Ctrl+Z. This may well have its artistic appeal. But the becoming, the experiencing, or the certainty that the celluloid can blossom and pass in the world and in time are extinguished here. The poetics of the picture consist of its uncertainty, its different temporality, and the constant play with not knowing and hoping. Anyone who has ever made a roll film in his laboratory of trust and had to wait two days for the developed images knows this feeling.

But precisely at the moment of its disappearance, filmmakers turn back to celluloid and search for the potential of this unique carrier material. And it remains to be hoped that the films of Kayako Oki and others, the work of the artists’ labs, and the careful curation of such themes will, in the long run, lead to the disappearance of the celluloid being stopped where it begins: in the production of the raw film material. Let’s be honest: Who can live without skin?