Endless Summer

Nevena Desivojević on Bright Summer Days

Time seems to be standing still in Nevena Desivojević’s Bright Summer Days in which two sisters re-encounter between departures, absences, and returns. The film is now nominated for the New Critics, New Audiences Award 2026.

In this quiet, small town in northern Portugal, time, as the cliché has it, moves more slowly. So it is for me, patiently waiting for Nevena Desivojević at a café in Vila do Conde, where we agreed to meet to talk about her short, Bright Summer Days (2025). I have all the time in the world, as an old lady brings out my €1.60 coffee, teeth bared as she smiles. This café is perched on a platform accessible only by stairs—Desivojević cannot seem to find. She calls to say she’s five minutes away, still searching for the mysterious steps, and the patience I feel reminds me of the kind I experienced while watching her film. Her delay only emphasises how time can feel distended; as you wait for something, it stretches unnaturally and behaves differently than usual. Time shifts shape, and in Bright Summer Days, it all but ceases to exist.

Desivojević grew up in Serbia, where her love for film first began to take root. At a very young age, she knew she wanted to create, staging impromptu theatre plays with her best friend, using pocket money to acquire makeshift props, and bringing their imagined worlds to life. During high school, film directing sparked her interest, and she prepared for the film school entrance exam in Belgrade, Serbia, which accepts only five students each year. “I started reading those books and I understood nothing,” she recalls. “It was too complex for me. I come from a small town.” She got into studying production instead, but that didn’t stop her interest in filmmaking. Undeterred, she found herself sneaking into 8 AM documentary classes, and finally began her studies in earnest once she moved to Lisbon.

It was there that she made her first short, Outside the Oranges Are Blooming (2018), a meditative portrait of a solitary man wandering through a vanishing village shrouded in fog. Like Bright Summer Days, her debut resists conventional narrative structure; rather than relying on a linear plot, it leans into feelings, silence, and the evocative spaces between words. It is these pauses that anchor Desivojević’s storytelling, those emotional undercurrents where time stands still.

Bright Summer Days premiered in the International Competition of the 33rd Curtas de Vila do Conde. We meet in between screenings, hidden from the scorching Portuguese sun, right before she is to leave again, her suitcase beside her. While Desivojević is something of a Curtas regular, this is the first time she’s attending the festival as a filmmaker. Her newest film is the first in a series of four, each tied to a season. “365 days a year, I find myself nostalgic. For this film, the feeling started after a loss in my family. I felt a big absence, being away from my country [Serbia], and in this absence, my imagination grew… Almost like I was returning to childhood. I wanted to bring this hyperbolic feeling to the film.”

The first shot of Bright Summer Days is a still picture: two sisters, laughing, carefree. As it turns out, that image is the only surviving vestige of a failed scene. “Well, no mystery. That scene was shot as a normal scene. It wasn’t meant to be a photograph. But we couldn’t edit it, nor could we reshoot it, as it was our last day of shooting. So we decided to just start the film with this, like Chris Marker’s La jetée.” It lays out the film’s visual identity, as well as its understanding of time: it is standing still.

Everything in the film moves slowly. The Serbian sisters are nameless. Standing in front of a lake, an awkward distance separates them. From the start, the film creates its own sensory world, with minimal dialogue and a slow pace. The murmur of a nearby river, the gentle creak of a swing: each aural and visual detail invites us into a space where feeling takes precedence over plot. Watching Bright Summer Days, I find myself breathing in the air of the world Desivojević created, one where minutes go by as if they were hours. “I don’t want the spectator to get to know something. I want them to feel something.”

A distinctive trait of Desivojević’s filmmaking is her rare ability to entrust the viewer with a kind of interior authorship: she allows the film to grow within me—organically, almost imperceptibly—until I become more than a passive spectator. When the sisters begin to speak, it feels less like exposition and more like eavesdropping, as though their words were intimate fragments of a much larger, unseen history. I am thrust into the middle of the exchange, as if I were a fly on the wall that’s landed just moments too late to grasp the full context.

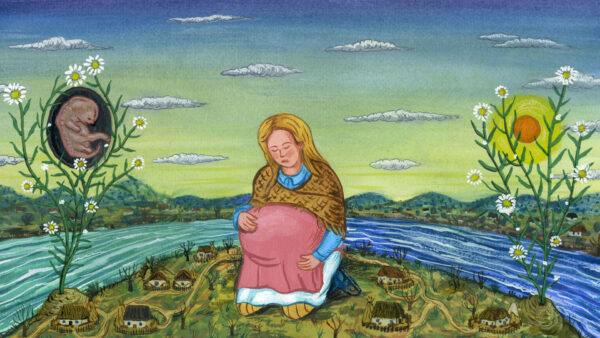

© Bright Summer Days (Nevena Desivojević, 2025)

And yet, the lack of clarity doesn’t alienate so much as compels. The dialogue is reminiscent of the opening scene of Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of The Wolf (1968), where Alma, played by Liv Ullman, talks into the camera with unwavering directness to her husband, recounting events with the unsettling calm of someone who assumes we already understand. There are no overt explanations—only a deep, enigmatic trust. And like Bergman, Desivojević beckons us into the shadows without a map. As the film unfolds, the mystery of these women only deepens. “It had to be a fragmented story. There was no room to develop it more, so I just gave you a glimpse of what it could be. It’s tricky because the line between arrogance and trusting the viewer is very thin.”

Desivojević navigates that thin line effortlessly. The sisters’ conversation could be interpreted in many ways, but the film’s visual language spells out the “distanced proximity” between them, long before they start speaking. There lies a particular timeless mystery in the cinematography. Though captured digitally, the images carry the textured warmth of 16mm film, as if memory itself had been threaded through the lens. It’s a quality that heightens the authenticity of the wooden house the two sisters seem to reside in as they reunite. Unsurprisingly, director of photography Gregor Božič took inspiration from Peter Weir’s Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), a film where the natural world seems alive with secrets and incantations, and how the earth itself is captured evokes all kinds of mysteries. Not unlike the murmuring river in Bright Summer Days, the rocks and plants seem to talk and become characters of their own. In both films, the loudest voices come from those who cannot speak.

Silence is omnipresent in Bright Summer Days, and stretches across its fourteen minutes. As the short unfurled, I found myself holding in my breath, afraid to interrupt its quiet spell, yet finding peace in moments where time didn’t feel real. Bright Summer Days wouldn’t feel out of place as an installation at a contemporary art museum—there’s something almost physical about it that makes you want to stand still as you watch it, taking time to let it drag you in. As I waited for her at the café, Desivojević’s late arrival brought me back to that same quiet place—standing still, allowing those extra twenty minutes to offer me introspection before externalising all my thoughts about the film. An extension of its contemplative sprawl. Bright Summer Days is not a story but a feeling.

Which isn’t to say the short forsakes narrative altogether. In between the silent sounds of the water, a sense of familiarity emerges within me as the sisters speak. They haven’t seen each other in years—one left to build a life elsewhere, while the other remained, caring for the family. “It’s common in Balkan families. We come from relatively poor countries, and most people migrate. Those who stay in the Balkans think that you’re living in heaven once you move away. I wanted to bring this Eastern gaze of the West to the film.” As someone with a fragile bond to their ancestral turf, I smile, finding comfort in her words. “Someone went away in search of their happiness, and their life there is good, so they stay, but there’s always someone who is left behind.” This loneliness lingers in the space where Desivojević seems to suspend time. From the sisters’ brief, subdued exchanges, the emotional distance between them becomes achingly clear. The director took inspiration from The Damned Yard, the 1954 novel by Yugoslav writer Ivo Andrić, where the complex, contradictory feeling of facing someone you were once close to is captured with haunting precision. How do you hold the joy of reunion alongside unspoken resentment? They found happiness; you’re still searching. That is the essence of Bright Summer Days’ story.

This quasi-narrative rests safely in the invisible hand of the film’s visual identity. Carrying the emotional weight, the cinematography gives shape to memory, distance, and silence. Through lingering shots, textured warm light, and a pace that resists urgency, the director allows the camera to tell the story the characters cannot. The “fragmentary and minimal” narrative, in Desivojević’s own words, is completed through what we sense and see.

Though meaningful, the story is not what carries this film. Rather, its imagery and pace feel most tangible—its slowness makes me stand still within myself, allowing me to reflect on why I feel so touched by it. As it is rare for a short to evoke that introspection not just afterwards but already in the very act of watching, Bright Summer Days manages to reach a level of intimacy to cherish. Desivojević takes her time to get to you, and as a viewer, you’re willing to offer her that time—she trusts that you will, as she did while I waited for her in Vila do Conde.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #7—a tandem workshop set during Curtas Vila do Conde and FeKK – Ljubljana Short Film Festival—and edited by workshop tutor Leonardo Goi.

Bright Summer Days was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2026 at Curtas Vila do Conde by Alex Petrescu, Elena del Olmo Andrade, Emily Jisoo Bowles, Hana Kreševič, Hava Masaeva, and José Emilio González Calvillo, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #7.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism, the European Workshop for New Curators, and the New Critics & New Audiences Award are co-produced by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme, and in collaboration with This Is Short.