Everything But The Kitchen Sink

I Am Good At Karate

Jess Dadds’ social realist film is a tribute to the power of an individual to fight against the crippling issues caused by mental illness.

Much like its feature film cousin, the history of British short film is consistently intertwined with the tenets of social realism and the ‘the kitchen sink drama’ aesthetic that has been a large part of British cultural output since the 1960s. With working-class protagonists, council estate locations, and a preoccupation with wealth inequality and the general classicism inherent in British society, the eminently recognisable elements of this strain of UK cinemas have become almost reassuringly familiar for audiences worldwide.

While Jess Dadds’ I Am Good At Karate ostensibly seems to focus on a single issue (namely mental health), its use (and subsequent skewering) of standard social realism tropes turns the film into something infinitely more complex. The initial exploration of depression and its relationship to the film’s main protagonist becomes a playground in which issues about tradition and modernity, the stranglehold that notions of class still have on British society, and notions of gender stereotyping all vie for attention in a film that is as sharp as it is playful.

The protagonist of I Am Good At Karate–never named though given the sobriquet ‘Karate Kid’ in the credits–is filled with self-doubt and loathing. Their own deep-rooted insecurities and mental health problems take the form of a demon, made up of shredded football shirts, who follows them around, intoning damaging epithets such as “go and play in the road” and “I hate you”. But, even when faced with despair, the karate kid must find ways to fight back. Luckily, they know at least one thing they are good at.

While the film is something of a paean to the power of an individual to fight back against the often crippling issues caused by depression and mental illness–the ending scenes in which the demon gets what for are literally and figuratively ‘punch in the air’ moments–it is also a reminder of the circumstances in which these conditions bloom. The Kid begins the film by mentioning how their brother, his best friend, and their grandmother all suffer from depression and take pills. There’s a sense of a cycle of depression, a never-ending cavalcade of suffering and pills that will pass from one generation to the next. When the Kid mentions their depression, they put their pills down the drain—and also, in a cheeky and insouciant shot, spits some remains directly down onto the camera. There’s a sense that the Kid has the chance to break a cycle, to move beyond old ways of being told how to live.

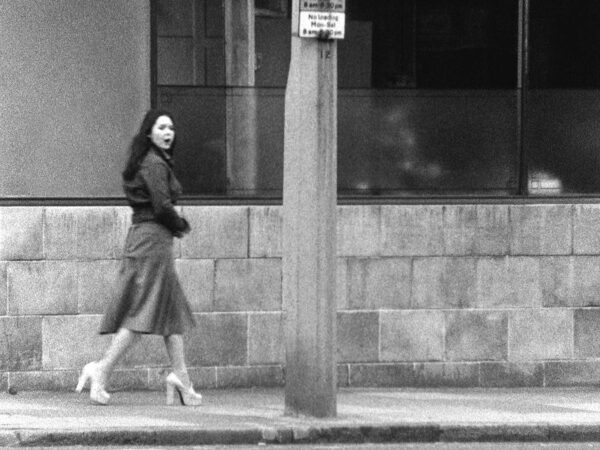

As the demon follows our protagonist around the council estate in which they live, we get the feeling of a place that is in some ways suspended in time, stuck from ever being able to progress. The imagery is from the world of social realism—moments of black and white 16mm footage of crumbling walls, England flags covering shattered windows—a world familiar to many, but this familiarity is a sign of stasis and stagnation. As the demon makes empty promises to the Kid–“I will make you grow powerful from the decay,” it intones–and the Kid begins to believe them (with eyes growing dark, as the film flirts with horror), there’s a feeling of helplessness. But as the Kid regains some sort of power within themselves, there’s a rush of energy to the film, a sense of change.

The Kid themselves–played with an unaffected brilliance by Hayley Archer–is representative of not only a new generation of people dealing with mental illness but a new generation of people trying to move outside the roles that many would believe their class and circumstances would force them to play. The Kid’s ambiguous gender throughout the film touches upon the throwing off of old societal mores, while the demon being made of shredded football shirts speaks of being forced to fit in: one must like football because everyone else does. But the Kid soon finds the strength to play by their own rules.

For all its introspection, I Am Good At Karate is a remarkably funny and often joyous piece of work. Dadds plays with the often dour natures of social realism, and reconfigures them. Instead of the long and slow takes often associated with drama, the film revels in quick cuts and playing with space. The ‘demon’ itself strikes a line between the serious and the ridiculous. The sad and the dour are consistent presences, but they are always being undercut.

I Am Good At Karate is never crass enough to suggest that mental illness is only the preserve of the poor and deprived. But, as the end credits roll over radio news reports about the connection between mental illness, it does question how the situations that many find themselves in can be a major contributory factor. As it re-frames traditional tropes it questions the political and social mores of a cultural past and present that is, more often than not, lamented yet slightly romanticised. The film finds a sense of hope and capacity for change among the windswept streets and broken buildings.

There are no comments yet, be the first!