Extra Bright I Want You All to See This

All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes

Haig Aivazian’s most daring leap into the world of film and a cogent attempt to tie together his interests through the form of found footage.

Haig Aivazian is probably a name that is not too familiar to the wider world of cinema; after all, he’s spent the past decade or so staking his claim in the realm of contemporary art, acting as the current artistic co-director of the Beirut Art Centre. His latest film, All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes, is in some ways a culmination of his work thus far, serving, most prominently, as the centrepiece of a 2021 retrospective exhibition in Chicago titled “All of the Lights”. Through viewing his past artwork, installations, and audiovisual lectures, one can glean Aivazian’s primary artistic interests: examining how the modern distribution of images shapes narratives, the current instability of the Middle East, and the perennial link between innovation and state violence. All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes, is, as of now, his most daring leap into the world of film and a cogent attempt to tie together his interests through the form of found footage.

The essay film as of late is in the middle of a minor resugurance with the likes of Theo Anthony’s All Light, Everywhere (2021), whose association of police body cameras and other tools of control with the historical development of the camera is reminiscent of Aivazian’s film, and Adam Curtis’ sprawling Can’t Get You Out of My Head (2021), making waves among critics and landing on year-end Top 10 lists. These are documentary films that eschew the usual signifiers of talking head interviews and linear narratives, opting for a less restrictive, free-flowing assembly of disparate images and observations. In the scope of the average cinephile’s imagination, the pioneers of this style may include perpetual favourites like Chris Marker or Harun Farouki, yet, by taking one step into the art world one can view a whole host of influential figures, such as Korean artist Nam June Paik, known for his experiments with audiovisual collages and television broadcasts in the early 60s. It speaks to the striking disparity between the analogous spheres of cinema and contemporary art, with innovations in the latter slowly trickling down into the former, separated through opposing distribution channels, i.e. the gallery versus the theatre hall or streaming service.

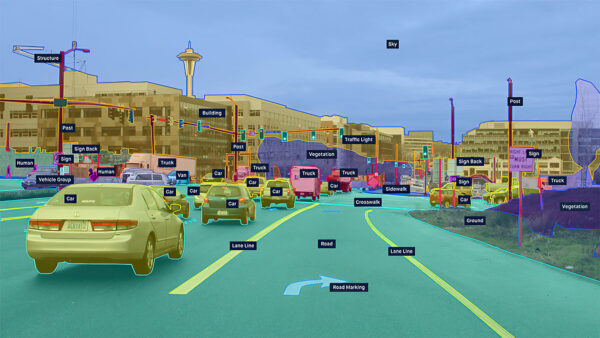

That is to say that All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes doesn’t exactly follow in the footsteps of cinematic tradition, as much as Aivazian is following the trail of fellow video artists like Arthur Jafa or Phil Solomon and their work in the space of found footage. Aivazian’s film, as such, consists of a playful mix of surveillance footage, documentary excerpts, corporate infographics, and cellphone videos (some even credited as coming from WhatsApp), ranging from the intensely political to the trivial. Found footage itself, in its contemporary form, is probably one of the most prominent audiovisual innovations of the past decade. After all, the democratisation of portable video through the proliferation of smartphones is a relatively recent phenomenon, one which, coupled with social media, has created a new media landscape where the average person adopts the role of spectator, image-maker, curator and subject, practically any event can be witnessed from the ground floor. The goal of found footage is, as such, guided by a certain minimalism, it recycles rather than produces images in an era where we’re constantly indebted with audiovisual stimulus at every corner. Aivazian’s role as the filmmaker is, consequently, one of curation and assembly, taking in all the raw material and detritus of the internet, and cutting through the noise by streamlining it in a way that suggests coherent ideas and a reflection of personal interest.

The main throughline of Aivazian’s film is an exploration of the multifaceted use of light throughout history, purportedly following its genealogy and the human attempts to harness it, to triumph over darkness and the forces that lurk within it or otherwise. The first two scenes practically instruct the viewer how to watch the film, clearly laying out the dichotomies Aivazian intends to wrestle with. The film begins with an excerpt from a documentary about the abduction of whales in the 16th century, hunted for the oil in their heads. The slaying of these beasts is framed as a victory for humankind over creatures of the unknown, turning fear into enlightenment with their oil-powering lamps. This is the first definition of light espoused in the film: light as liberation. What follows is a hard cut to the chaotic scene of a row of police cars at a sheriff’s office, taken from a local news channel’s Christmas coverage. Their blinking lights are synchronised to the symphonic metal song ‘Wizards in Winter’ by Trans-Siberian Orchestra, and eventually devolve into a disorienting burst of flashing red and blue light that floods the screen. The message is clear, that light is also an essential tool for policing. It is this contrast, between light as both an instrument for freedom and control that recurs throughout the film.

By teaching the audience how the images function, Aivazian grants himself the freedom, in his interweaving of historical fact and contemporary events, to present tangents in a less structured manner. The footage is presented erratically, in some instances violently cutting between smartphone videos of Beirut civilians using fireworks as weapons against law enforcement, YouTube videos cataloguing the development of oil lamps and their swift adoption by Victorian police, and infographics detailing the ability of street lights to detect human activity and harvest data. Aivazian’s frantic manipulation of the footage feels fresh, yet the form practically calls back to Soviet intellectual montage, as meaning is not created from individual segments alone but through the harsh juxtaposition of images, at times literally layered on top of each other through chaotic digital compositing. Aivazian manages to strike a very fine line, not making the film overly structured or overly didactic, providing just enough leeway for the viewer’s mind to roam free, to form their own connections between images and come to their own conclusions regarding the historical use of light.

All Of Your Stars Are Bust Dust On My Shoes

What grounds the film, however, is Aivazian’s interest in cataloguing the recent turmoil in the Middle East, and as with traditional intellectual montage, the primary thrust of the film comes from the evocation of the political. Light is harnessed as a political tool in his home country of Lebanon, with fuel shortages in 2021 causing state electrical generators to shut down. The footage Aivazian sources, places us at a ground level of the crisis, with civilians heckling the building of the Lebanon State Electricity Co, declaring them as thieves who looted their money and denied their electricity. It’s a very effective microcosm of the gross income equality that plagues the country. Jumping forward a documentary excerpt describes Syria, as a result of the destruction of the civil war, as being physically dimmed on the world map, before cutting directly to surveillance footage of a prisoner sentenced to pitch dark solitary confinement. The message rings clear: light is a basic human right woefully denied.

Furthermore, Aivazian also draws a heavy focus on the 2019-2020 Lebanese Revolution, an event he portrays as heavily documented through amateur cellphone videos. In these segments, the connection between found footage and pop imagery becomes incredibly evident. Inevitably, because of how the internet functions, there is a tendency for real world struggle to be swallowed whole and reconstituted, flattened as ‘content’, occupying the same cultural space as fictional films or TV shows. Aivazian seems to be aware of this, leveraging our familiarity with imagery now considered iconic. Particularly that of Lebanese citizens shining bright green laser pointers to disorient law enforcement, an image incredibly reminiscent of another act of protest, the impromptu laser light show during the 2013 Egyptian protests for reform, with thousands of laser pointers shone on a helicopter. In the context of Aivazian’s film, it becomes a powerful symbolic gesture of the ability of light to act as a tool to speak truth to power.

The connection between pop aesthetics and politics is made clearer in an unsettling montage, which places a horrific audio track clinically describing how people donated their eyes to those who lost theirs in the revolution, over a video compilation of the cartoon trope of characters’ big white eyes being the only thing visible in pitch dark rooms. The act of dragging down real-world pain to the level of a cartoon is somewhat playful as if to condemn the audience for disregarding the severity of the former. But there’s also an interesting notion at work, suggesting how, the lexicon of images provided by the internet, the fictional frivolous pop imagery and the like, can be used to make sense of real tragedy, having an actual bearing on reality and vice versa.

This idea of simplified, reductive forms of an image being capable of creating a large tangible impact later comes in the footage of a bedridden woman protesting Lebanese public officials, ruefully declaring the film’s title “All of your stars are but dust on my shoes”. Later on we see hordes of people adopting her message, chanting “All of your authorities are but dust on my shoes”, a strange trickle down effect is at work, from real pain, to viral clip, to icon of the revolution, to rallying cry. The procession of the image very effectively cuts to the core of found footage as a form that legitimises real-world experience captured through video whilst rendering it as purely symbolic, another link in the chain of images assembled.

Aivazian’s film is yet another striking example of how the genre of found footage continues to innovate, being one of the few modern forms to crucially interrogate the current political landscape and the expanded definition of the image and of cinema. As it remains, there’s still so much the modern film scene can learn from the world of contemporary art, and if Aivazian’s efforts to distribute All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes through film festivals is any indication, we can hope that the gap is bridged sooner than later.

There are no comments yet, be the first!