Familiar Haunts

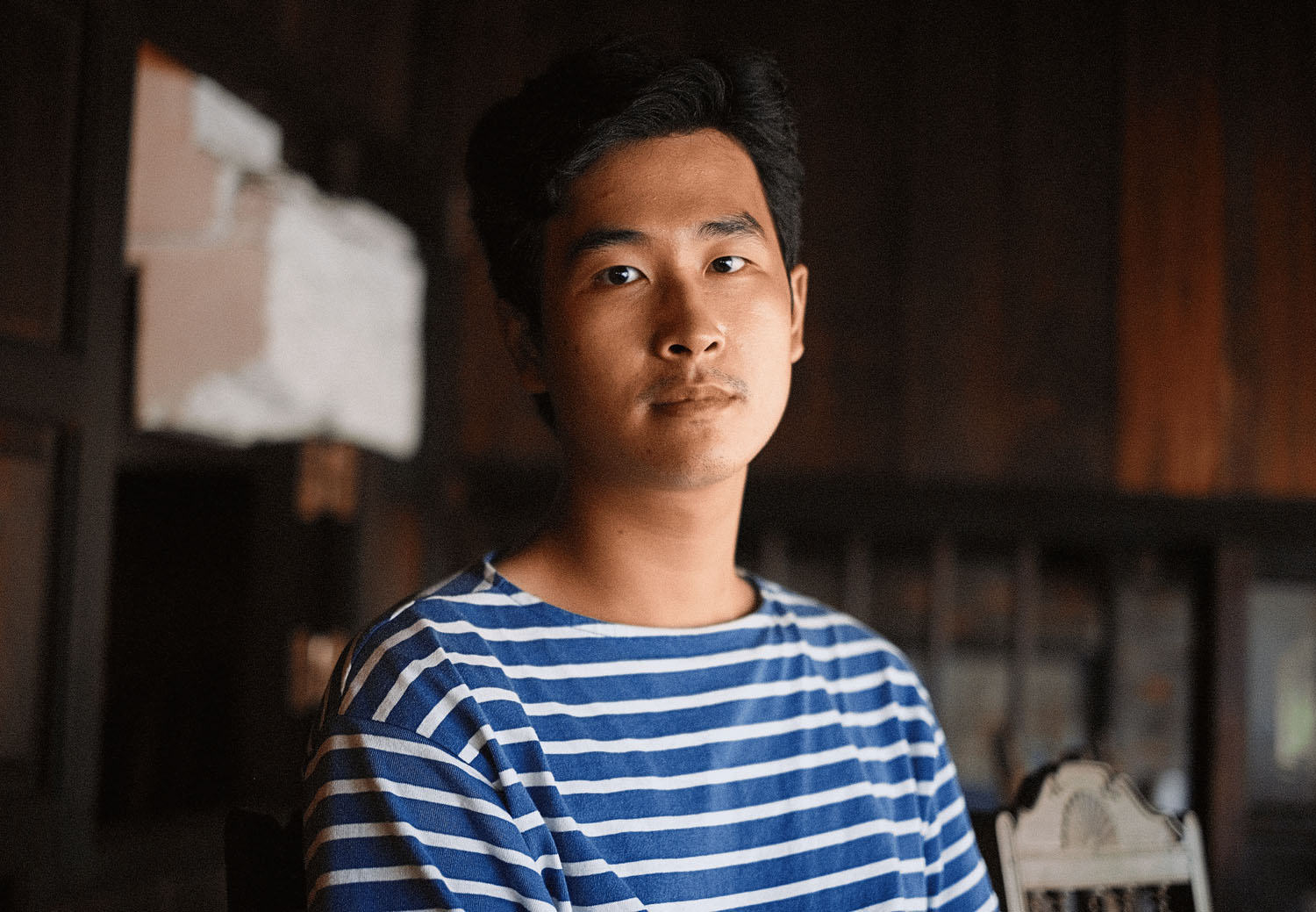

Interview with Lê Ngọc Duy

Set in Da Nang, Lê Ngọc Duy’s Queer Palm-nominated Before the Sea Forgets finds a gay tourist couple confronting the violent echoes of history. In this interview, Duy discusses the intersections of queerness and resistance and the importance of restoring the truth of his Central Vietnamese heritage.

For years, Lê Ngọc Duy wanted to become a filmmaker. Even though he had considered enrolling in university to study directing, it was only when a friend encouraged him to apply to Doc Cicada, a documentary workshop in Hanoi in 2020, that his creative future would blossom. “It’s where I met my first lover—my mentor,” he laughs. While developing an experimental documentary in the workshop, his personal life and the possibilities of what cinema could be opened up before him, beyond what he saw on HBO, Star Movies, and TV.

Since then, Duy has become one of Vietnam’s most distinct voices, partly shaped by his own work as a programmer for grassroots screening initiatives like A Sông Collective and Con Nhà Nghèo Cinema (Cinema of the Peasants). His interest in mixing queer love and historical inquiry would come together five years later in Before the Sea Forgets, the short film he premiered in the Director’s Fortnight section of the 2025 Cannes Film Festival. Set in Son Tra peninsula in Central Vietnam, the short follows a gay tourist couple searching for a forgotten Vietnamese soldier’s grave.

As they traverse stunning seascapes, lush forests, and abandoned buildings, the two discuss their fathers’ wartime memories while young skateboarders interrupt the silence with their tricks. Through the film’s audiovisual poetry, the contours of the sociocultural and historical-political erasure of Vietnamese history come to the fore, and the separation between and across generations becomes clearer. Timed with Vietnam’s 50th reunification anniversary, the film draws parallels between the relationships of soldiers, skateboarders, and same-sex couples, creating questions about the complicated relationship of the country with comradeship, patriotism, and “official” history.

In our conversation ahead of the Festival du Nouveau Cinéma in Montréal, where Before the Sea Forgets was set to compete in the short film competition, Duy discussed growing up in Central Vietnam, the political forces that shaped his cinephilia and upbringing, and how independent Vietnamese cinema survives on the fringes in the absence of state support and amidst continuous, aggressive censorship. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

What was it like growing up in Da Nang?

It’s the premise of everything for me. Most of my inspiration comes from my hometown, and I’m in love with its landscape. When I think of what to describe and portray in my films, what instinctively comes to mind is a mix of the following: my people’s accent, the peninsula in Da Nang, and the beach. It comes naturally to me. Since Da Nang is in Central Vietnam, I was interested in the regional dialect and accent, which is underrepresented in Vietnamese cinema. Most propaganda films from the 80s and 90s were made by the North Vietnamese and with a North Vietnamese accent. Nowadays, because the film industry is [concentrated] in the South, there are very few traces of the Central dialects on screen.

I didn’t know much about the region’s history until a few years ago. Recently, I discovered a notebook belonging to my father’s late friend in the Southwest border war between Vietnam and Cambodia, and I learned more about my family’s history and that of the region as a buffer zone. After the French colonisation [mid 20th century], the United States invested heavily in this area to build the second-largest military base in the South of the country. After the Geneva agreement in 1954, it was just two cities away from the border between the North and the South. It was also the first place that the French colonisers set foot on to rule the whole country. The region carries a lot of historical weight.

Where did this film begin?

I wrote the first draft in May 2024. Then I made a hybrid documentary focused on the Southwest Border War between Vietnam and Cambodia at the New Asian Filmmakers’ Collective Filmmaking Workshop. But at that time, I had very little time to make it, so I didn’t have a chance to record my father[’s testimony] and dig deeper into the family archives. Those were the first, brief encounters with the materials and my flash imagination of the films to be. When I got back to Vietnam, there was something lingering in my heart, so I started writing a script for a fiction short, partly based on that story.

The original title was The Tomb of My Heart, correct?

Epitaph of my Heart, originally… Wait. How did you know that? Did I tell you?

I found photos online.

Oh. [laughs] It was supposed to be Epitaph of my Heart instead of Before the Sea Forgets, with a Vietnamese name as well. You get why it was named Epitaph of my Heart, yes?

I do. [laughs] Going back to the film’s origins…

The original inspiration came from this story—the one about my father and his late friend who fought in the Southwest border war. But it’s also partly inspired by my own experiences of love—particularly the queer elements within the film, that’s me… I tried to combine these two threads—history and family, but in a symbolic way. While the short is not explicitly about the war in the past, I wanted to include that this city was and is a monumental place. Also, I was obsessed with the death of a soldier and a sad, doomed love.

One of the most striking images in Before the Sea Forgets turns skaters into tableaus of soldiers lying on the ground of an abandoned villa. Reenactment plays a role in how you explore memory, queer expression, and Central Vietnamese heritage. Where did those interests come from, and how did you arrive at that image?

That scene isn’t really about the old generation versus the young one. The skaters are more like reincarnations of those soldiers in today’s society. They just don’t wear uniforms anymore—but they still act like soldiers. They are also “dead,” in a way, like the soldiers of the past. They aren’t solemn or upright. They have their own expression, music, style, and manners. In a way, they are the fathers of contemporary society. Personally, I’m quite rebellious towards many things going on in our society. [The film and these images are] a subtle expression of rebelliousness against the perspective of the state about history, about everything.

How did you arrive at the music in the film?

I always felt the film should start with a love song; that the music should transcend time, like the way a whistle or a simple melody does. The dialogue of the characters also adapts to it. When the music is mentioned again [within the film] as a kind of wartime souvenir, it became clearer for me. My intention was not just [to insert] a random melody, but [to create] a song of affection given to someone you hold dear. Soldiers in the past didn’t have many means of entertainment. Maybe they had a guitar to play with. Those who had artistic talent would come up with a random tune that’s easy to remember. I kept the concept the same for this.

For the skaters—who live in the present—they have their own music. It made sense that they should have their own lyrics too. I tried to make it meaningful, like the lyrics filled up the void of the song in the past.

© Before the Sea Forgets (Lê Ngọc Duy, 2025)

The film features an excerpt from Thanh Tâm Tuyên’s novella Faces (Khuôn mǎt), which follows two friends who meet an older man named Châu, who invites them to his residence to share stories about Hanoi of the past. This excerpt is read to us by the young man (Tran The Manh) as the camera pans across the beach, as if it’s searching for the older lover amidst the sea of tourists who’ve slowly taken over the island. Could you give us some context, especially for those who are unfamiliar with Thanh Tâm Tuyên’s work?

He’s better known as a poet, one of the most avant-garde ones in South Vietnam. He’s originally from the North, grew up in Hanoi, but in 1954, he migrated to the South because of the land revolution, when the regime massacred many bourgeois families who gave food to the revolutionary soldiers fighting the French. The excerpt from Faces [used in the film] narrates how a boy borrows features from other faces to remember his lover. After 1975, all of the intellectual property made and circulated by the Southern Vietnamese figures was executed and erased by the North. They don’t recognise these and still ban them even now. I can only access the novels and poetry because other Vietnamese poets have posted them online.

How did the Singaporean production company 13 Little Pictures get involved?

I met Looi Wan Ping, the founder of 13 Little Pictures and his old company WBSB Films, at the Cambodia workshop. He was the first one I invited on board when the project was just a draft, first as a producer, then as a cinematographer.

As a company, 13 Little Pictures and WBSB were more involved creatively. Wan Ping and I discussed cinematography, story, everything. Not [necessarily] for the funding. In terms of production, everything in this industry [suggests that] producers should be more involved with securing funding for the film. The main producer was CJ in Vietnam, but now, it’s a Singaporean production. Wan Ping’s role and Vietnamese producer Minh’s roles are now quite equal. 13 Little Pictures helped me a lot with the legal status of the film and the creative process. The Vietnamese producers were more involved with line production and logistics and everything here to make the film.

The story is set in Vietnam, and it features mostly a Vietnamese cast and crew, but it is considered a Singaporean production. What’s the process of applying for screening rights in Vietnam? And why is it no longer listed as a Vietnamese production?

Similar to other countries, we have to apply for age categorisation and censorship approval first. My film was 100% banned. By law, all films—shorts or features—should be submitted for approval to screen in Vietnam or before they’re submitted to festivals. We know they will ask us to cut the film if it’s not that sensitive. If it’s more sensitive, then you either cut the whole thing or get a total ban. In other cases, international co-productions are a means to “belong” somewhere when Vietnam doesn’t accept the work. Taste belongs mainly to Singapore, and Viet and Nam primarily belongs to the Philippines.

The film tries to return cultural memory to Vietnamese audiences, yet it isn’t allowed to be screened in Vietnam. Does censorship feel like part of a larger erasure?

That’s hard to answer.

I’m sorry. Am I getting you in trouble?

No, I like the question. For Vietnamese independent filmmakers, being censored has almost become a given. To be uncompromising [in your filmmaking], you have to accept that your film will screen elsewhere. It’s [like] a heritage we’re already accustomed to. Some make two versions of the same film—one “official” to show the censors and another for international film festivals.

But even if our films are allowed to screen domestically, we don’t get recognition from the state the way commercial or propaganda filmmakers do. There’s no national funding, so we have to rely a lot on the international scene for that. Even for interviews and press releases. When I imagine screening [my film] domestically, I always think of it as an independent film screening on a smaller scale. It’s how independent filmmakers in the prior generations screened their films to reach audiences. Not in the “official” cinemas.

The decision to adopt a more experimental format is also driven by funding constraints. I don’t think I was brave enough to make it experimental from scratch. When I think about [the film’s script], I think about it as a narrative. But due to a lack of money and [other support], we have to make it another way. I come up with a different approach to making films based on what I want to tell. We [face] limits, but find ways to overcome them.