FeKK Correspondence: Nomads in Conversation

As part of our FeKK Ljubljana Short Film Festival coverage, participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #7 reflect on a film festival’s responsibilities in breaking the canon.

Querida Elena,

How strange that we, both Spanish speakers, should have to write this correspondence in English. That this language has become the lingua franca of film criticism across the global festival circuit is something we take for granted. The reason behind that is very simple, yet its causes and consequences are quite complex, not to say violent: there is more money for texts published in English than in any other language. Those among us who have full command of the idiom often decide to use it not out of pleasure but necessity. Yet if there is little money for criticism—meaning little money for thinking—then there’s even less for translations. And since translation has historically served as a means through which culture can spread, the fact that criticism is written and published mainly in English suggests there is precious little circulation of different ways of thinking about cinema, and film criticism itself becomes homogenised—a domain that’s only accessible to those who can read and write in this language.

It makes me very happy to see the FeKK Ljubljana Short Film Festival fight against this. Jelena Radić, a member of the festival’s production and programming team, told us that a good percentage of the budget is used to provide and translate subtitles into both Slovenian and English. This implies that, at least during the screenings, no local or international guest is excluded. I said “at least” because most of the films’ introductions and Q&As I attended were conducted in English. Hana, our Slovenian colleague from the critics workshop, told me that most elders and people outside Ljubljana don’t speak English. If the conversations are held in this language and most people understand, it should give you a hint about FeKK’s demographics: young, educated people who are all more or less related to the arts. Unlike most festivals (and film theatres), I saw very few elders at FeKK.

And yet the fest is all about real inclusion. I’ve never felt so welcomed at a festival as I did at FeKK. The opening ceremony was as warm as a screening can get, and the party that followed was marvelous (basically all events were accompanied by drinks and food, a not-so-common feat nowadays). The festival puts a great deal of effort into making sure everyone feels comfortable and safe at all times. Surprisingly, while at FeKK, I managed to find some time to read and came across this quote from film scholar Jules O’Dwyer concerning Roland Barthes’ essay “Leaving the Movie Theatre”: “For Barthes, leaving the movie theatre was an exercise in how to live together”. I think those words summarise quite eloquently what FeKK strives to achieve as a festival, and what we did as a group.

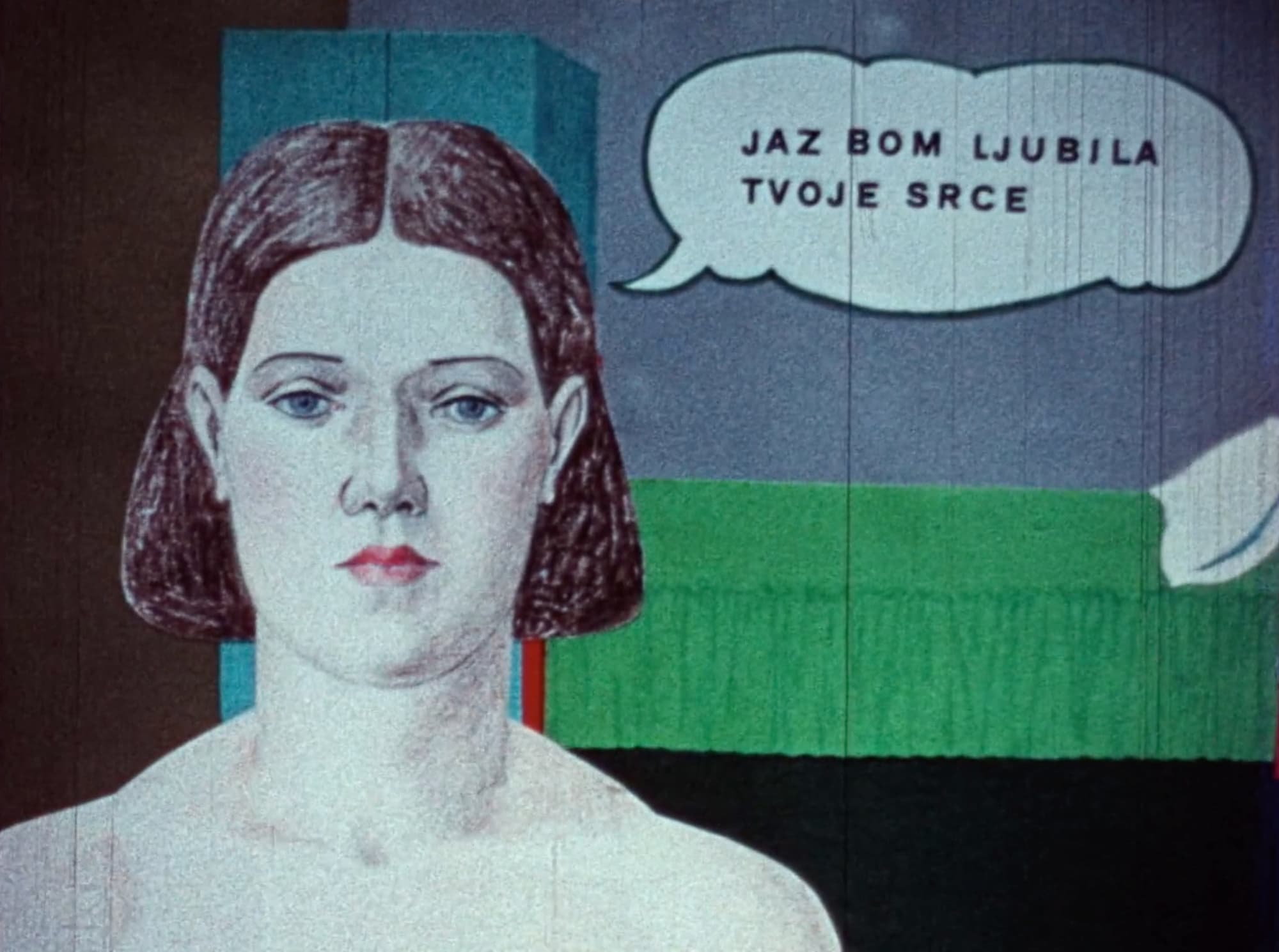

As for the programme, the screening I was looking forward to the most on my way to Ljubljana was “From the Archive: Anatomy of Yearning”, which consisted of nine experimental Slovenian shorts restored by the Slovenska Kinoteka. Personally, it’s always a pleasure to encounter films from a country I’m not familiar with. The programme “ranges from experimental visions to teenage stories in which dreams are not a consolation but an ignition for longing”. Most of the short films did not disappoint, but the bridge between dreaming and longing seemed a far-fetched attempt to bring together shorts that had very little in common. Most films were made between the late fifties and early seventies, and many relied on classical myths or local traditions from those decades. In Matija Milčinski’s Orpheus and Eurydice (1968), a couple succumbs to the same fate as the titular Greek lovers, but the tragedy is set in the urban landscape of Yugoslavia. Vasko Pregelj’s Dreams (1966) incorporates traditional music in a series of frames that use a collage technique, which makes them resemble Jackson Pollock’s paintings, while First Love (1976) is a sweet fairy-tale short that follows two young kids who fall in love just by looking at each other. Yet the one that struck me the most was Karpo Godina’s The Gratinated Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk (1970).

The title must be one of the weirdest I’ve come across, and bears no apparent relation to what unfolds onscreen. A lake is captured in a wide shot. The horizon, as if heeding Ford’s warning to never place it in the middle of the frame, appears in the upper third. Little cottages dot the lake’s shore; on the right, a woman swaying on a wooden swing. The setting, action, and shots’ composition remain the same throughout the short’s ten minutes, but between shots, the time of day changes. In one shot, the sun shines brightly and the water shimmers; in another one, the camera turns to raindrops blending with the lake; later on, the landscape is shrouded in darkness. How much time did it take Karpo Godina to capture all those different moments? How difficult was it to repeat the same composition over and over again? Suddenly, there’s a radical change: a group of men appears standing by the lake. Framed more closely in the next shot, they look directly into the camera: five Yugoslavian hippies.

The rest of The Gratinated Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk shows them striking different poses or singles them out, one by one, in close-ups, but the backdrop—the lake, the swing, the woman—stays the same. Sometimes, the structure is interrupted by frames that show four colour squares with different geometrical figures, numbers, and politically charged slogans. Karpo Godina’s film reminded me of Austrian avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka’s Poetry and Truth (1996-2003), another work where characters repeat the same actions over and over again. Kubelka’s repetitions served as a critique of advertising. I suspect Godina is also making a political statement. Though I lack knowledge of Slovenian culture to fully understand what that might amount to, the sense of humor conveyed by the many repetitions and the director’s disregard for conventional narratives feels rebellious. This subversion of an established order, whether formal or political, reminds me of the best avant-garde films that challenge the ways we perceive.

One of the festival’s highlights was the retrospective of David Lynch’s shorts. It’s amazing how the death of the American director earlier this year seems to have simplified the job for programmers around the globe. Don’t get me wrong, I’m fond of Lynch (though not as big a fan as you), but I find programming-by-hommage a little bit lazy and unimaginative, the ultimate way to reinforce a canon. At a time when critics and curators are trying to reshape cinema’s “official” history, it’s strange how Lynch has passed without any sort of critical revision. His more experimental shorts haven’t garnered as much attention as his features, but the filmmaker’s place in the canon needs no further buttressing, and insisting on programming him precisely does that. This, eventually, keeps us from getting to know filmmakers and traditions we might not be as familiar with. And if posthumous homage is a valid programming criterion, then why were there no retrospectives celebrating the oeuvre of Malian filmmaker Souleymane Cisse, who passed away just a month after Lynch? It bears noting that FeKK wasn’t the only festival that offered a tribute to the American cineaste this summer; Curtas Vila do Conde similarly wrapped with the eighth episode of Twin Peaks: The Return.

Anyway, I enjoyed both Lynch programmes I saw, and the indisputed highlight was his 1969 short The Grandmother. The film addresses fertility and the act of giving birth in a very gloomy way. Lynch blends it with the theme of domestic violence, but the mixture of live action with collage animation makes for an enjoyable counterpoint. The opening sequence, for instance, depicts the conception of the young protagonist, but the images are so abstract that it seems he is being born from the core of the Earth; The Grandmother melds human with vegetable life as if to suggest we are not that different. To boot, the tunnels from which the boy comes to life resemble both a pipeline and a digestive system, which adds new layers to the short. That the young protagonist should eventually succeed in “making” his own grandmother from scratch presupposes an obvious biological impossibility, but within Lynch’s universe of infinite associations, even the most absurd scenarios can come true.

The second programme, however, made me wonder if a retrospective should include a director’s oeuvre in its entirety. Before he pivoted to filmmaking, Lynch dabbled in painting, and watching this second slate felt like looking at the sketches of a visual artist; fascinating as that might be, I’m still not sure if the shorts selected would speak to anyone beyond the most loyal completists. If you didn’t know who Lynch was, what might you glean from shorts like Boat and Lamp (both 2003), which follow the director as he rides a boat and builds a lamp, respectively? Would you find any aesthetic merit in them? If so, what would that be? Personally, the only value I find in such works is that they show the man using his hands—they are portraits of the artist at work that remind you of how Lynch approached his surroundings in a very attentive and manual way. Seen in this light, the shorts might deepen your understanding of his entire oeuvre, but individually they don’t amount to much. Anyway, I just thought I’d stir some controversy around a filmmaker whose legacy has otherwise gone unquestioned since his passing. After all, isn’t such an uncritical reception what keeps artists locked in mausoleums?

I’m happy I’ll get to see you soon so that we can keep discussing this in person, and I really wish we could meet the others as well, thinking, through films, about the ways in which we live.

Very best, dear Elena.

Warmly,

José Emilio

© Oh Grow, Grow (Tone Rački, 1970)

Querido José Emilio,

A few weeks have passed since Kinodvor and the Slovenska Kinoteka bid their farewells to FeKK and its audience. Emblasoned with the edition’s motto, Keep the dream burning, the white T-shirt the festival gifted us is hanging in the drying rack as I soak in the strange feeling of writing to you in a language that doesn’t belong to either of us. Attending FeKK was a memorable experience; I will not forget its thrilling programme or the exhaustion that weighed over us as soon as the sun began to set. In this merciless landscape, I see us as two young nomadic travellers who, by chance, found some solace and comfort through conversations in their native tongue.

Now that I am back home, I still remember the “From the Archive” programme very fondly; I think you do, too. It was our first time entering the Kinoteka, notebooks and pens in hand. The films “address not only what we want, but mainly how longing shapes how we sense, experience, and see the world,” the programmer said, and the words echoed in my mind as the lights dimmed. The section didn’t seem to hinge on a clearly defined idea of yearning, resorting to mythology or dreaming as the only means to experience one’s desires. Nevertheless, Tone Rački’s Oh Grow, Grow (1970), a three-minute short that captures a woman’s doubts, desires, and impulses through an unsettling and handmade paper-like animation, stood out. The eerie movements of the woman’s body as she faces the camera vividly convey her emotional entrapment. As we gaze at her hand-drawn facial expressions, we register both the fear her impulses spark and the courage needed to overcome them. On the other hand, I remember feeling no sympathy for Karpo Godina’s The Gratinated Brains of Pupilija Ferkeverk (1970), a montage of jump-cuts depicting many half-naked and bearded individuals as they smoke, dance, and talk while addressing the camera. Captured in static shots that shatter the fourth wall (as when the hippies seemingly invite us to share a bottle of Coke with them), the short unfolds as a wistful chronicle of a sunny day at the lake. But Godina’s portrait of a bygone decade feels heavily romanticised, and his yearning for an idyllic past tiresome and unimaginative.

All through our week in Ljubljana, over Slovenian beers and neatly rolled cigarettes, we spoke plenty about the festival’s generosity. FeKK’s attention to the human dimension of festival-going played out in various forms and gadgets: wellbeing guidelines, safety tips, food vouchers, custom lighters, and long rolling papers encouraging one to Keep the green burning were handed out to guests. More specifically, FeKK’s focus on body politics and ostracised identities struck me as a stimulating prism through which to understand the world in which filmmakers and spectators alike process audiovisual stimuli. Through the “Palestine in Focus” programme, along with the opening ceremony, the team placed the genocide of the Palestinian people front and center of the edition. Razan AlSalah’s Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, and So Was the Nakba was one of the highlights. This docu-fiction hybrid utilised Google Maps to walk through the streets of Palestine, as that is the only way for AlSalah to visualise her return. The director’s digital avatar is the only entity capable of walking the route that the filmmaker is severed from and will never return to, as the land is violently devastated under Israel’s genocide.

The attention FeKK devotes to some of our biggest crises and the careful way it handles them are remarkable, yet fun is never sidelined. In fact, the edition celebrated joy as a means of resistance. In collaboration with the festival, the Red Dawn Collective organised a midnight screening of queer, feminist, and erotic short films. This group of curators is responsible for the International Feminist & Queer Festival Red Dawns, which offers alternatives to mainstream pornography, films where desire, sexuality, and pleasure are explored through a feminist and queer lens. The late-night pilgrimage to Kinodvor brought the queer scene together, building a fleeting sense of community under a complex premise: “In a world on fire—marked by ecological collapse, militarisation, and rising authoritarianism—what does it mean to insist on pleasure?” A fourteen-minute Swedish fantasy, Lasse Långström’s The Lesbian Alien Fisting Operetta on Venus (2023) follows the captain of the Sea Butches, a battalion of butches in a sacred mission to obtain the galaxy’s most powerful vibrator. This anarchist musical employs some classic science fiction tropes, mannerisms, and cliches to depict an extraterrestrial lesbian bar that has no room for shame or hesitation. The door opens on another universe as the “butches” arrive and the camera shows their vision adjusting to the ambience of the dark and humid room. Some laughs and some gasps erupted from different quarters of our screening room, stirred by this conscious vindication of homoeroticism. As an extraterrestrial orgy begins and bodies, tentacles, and fluids begin spilling on screen, The Lesbian Alien Fisting Operetta on Venus opens a window to a politically conscious, indulgent, and creative utopia.

After a long Saturday spent working on our assignments, each of us secluded in our hotel rooms, we met for drinks at the Kinoteka before heading to the closing party. The last days of August, a perpetual Sunday, weighed down on us as the festival wrapped. It was an evening of farewells, intimate conversations, and plans for the future—including a film club that will hopefully see the light of day sooner or later. Thinking about film, discussing our viewpoints, and sharing our love for the art is what brought us together as a collective. We hopped on the same airport shuttle, you and I, and as we boarded the most unstable plane we’d ever stepped on—after a night of oaths, tears, and many shots of something we couldn’t even pronounce—I realised everything was coming full circle. We ran into each other on the plane that shipped us to Curtas Vila Do Conde, and we left FeKK on the same flight to Madrid.

I will be meeting you again in between Zuritos, txakoli, and pintxos at San Sebastián. I hope Barcelona is treating you well.

Warmly,

Elena

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #7—a tandem workshop set during Curtas Vila do Conde and FeKK – Ljubljana Short Film Festival—and edited by workshop tutor Leonardo Goi.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.