Green Screen Gringo Comes Into His Own

Neighbour Abdi

Douwe Dijkstra’s films are always simultaneously making-ofs, as he lifts the curtain on movie magic that employs green screen.

When Dutch filmmaker and visual artist Douwe Dijkstra’s first short film, Démontable, appeared on the festival circuit late in 2014, it was a sensation of sorts. It won a special mention at Clermont-Ferrand, and I remember the whole team of the festival I was programming at the time, the now-defunct Kratkofil in Banja Luka, immediately agreed this should be our opening film. We were all aware that the special effects technology, at the time, was as advanced as ever before. We had seen various making-of’s from Hollywood blockbusters, but this time, a short film showed us exactly how it’s done, with wit, spirit, and style.

Dijkstra’s films are always simultaneously making-of’s, as he lifts the curtain on movie magic that employs green screen. In Démontable, a war occurs on a kitchen table as the invisible protagonist is having coffee. Airplanes and helicopters wheeze by; soldiers run, crawl and shoot, and explosions pop all over. In the film’s second half, we see the filmmaker making the set and actors putting on war fatigues and doing their thing in front of the green screen.

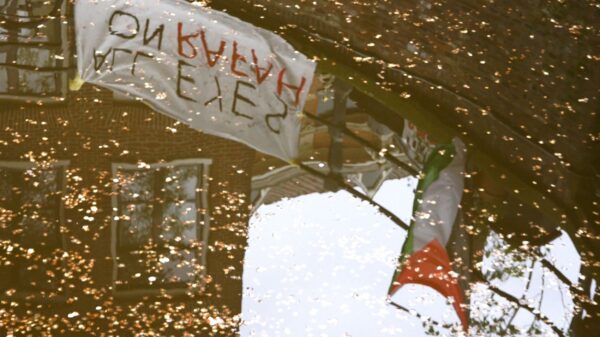

In 2016’s Green Screen Gringo, Dijkstra travels to Brazil and, carrying a portable green screen, walks around São Paulo, which is embroiled in the political crisis of the Dilma-Temer era. Here, he quickly, often in the same shot, alternates between what is made as an illusion on the green screen and his presence in the scene. The social-political side is very present, through short statements from on- and off-screen protagonists and a couple of touching and occasionally symbolic scenes showing support for the country’s marginalised—the indigenous and Black people and LGBTQIA+ population. However, the very image of a tall, white man invisible except for his bare feet behind the green screen makes the proceedings feel light, even if a clear feeling of turmoil is bubbling under the surface. This was the film when I started thinking of Dijkstra as the Green Screen Gringo. I’m unsure if he’s known widely by this nickname, but he should be.

All the previously mentioned films, including Supporting Film (2015) about the moviegoing experience and last year’s Eine Sekunde in Fränkli (made during a two-week residency at Kurzfilmtage Winterthur) are impersonal. There are no real characters in them; sometimes, it can feel as if they were made to showcase his enviable technical skills.

Now, the Green Screen Gringo seems to come into his own with Neighbour Abdi, which has won the Silver Pardino in Locarno’s Leopards of Tomorrow competition and is now screening in competition at Uppsala. The titular character is a man from Somalia of Dijkstra’s age (38), whose workshop is located next to the filmmaker’s in the town of Zwolle. After seeing Démontable, Abdi wanted Dijkstra to make a film about him. He had arrived in the Netherlands in 1995, escaping the war at home with his family, and didn’t land smoothly. Due to some bad decisions, he spent eight years in jail and three years as a “restricted patient”, a Dutch-specific form of therapy imposed by a judge. This helped him turn things around, and he is now a furniture designer, and as it turns out, a very talented one.

As Abdi, credited as co-writer, tells his story, we watch these scenes play out, and then inevitably, the layer of what’s happening on the green screen is removed for us to see the set. The dialogue overlaps across the scenes, produced by breaking the fourth wall on the one hand and with the cinematic illusion on the other, and the apparent notion that this is a documentary is challenged. The protagonist and the filmmaker work closely on the film. In the beginning, they are trying to make the small-scale model of Abdi’s neighbourhood as realistic as possible. Dijkstra brings a bag of grey sand, and Abdi agrees to its colour and texture, followed by his call to a friend to take a photo of the Mogadishu sky. The screenwriting here economically and convincingly introduces us to the protagonist’s memories and complex feelings about his hometown and country.

In the model of Mogadishu, a kid is playing a young Abdi who looks just like him—making one think it might be his cousin. As the boy runs on the green treadmill, he smiles, and so does a young man playing a soldier who gets killed. It’s fun to be on the green screen set, and they are clearly not actors—but this doesn’t take away from the film because we know it’s an illusion. Enough time and cinematic space have been dedicated to the audience getting used to it and accepting it as the world of this film and, by extension, Abdi’s world.

However, the protagonist’s words give a true dramatic gravity to the film, and this is a first for Dijkstra. Even if he touched upon some social issues in his earlier films, one can never achieve depth without a character to which the audience will connect. Abdi is likable and charismatic, and Dijkstra pulls us into the story through his trademark approach. The contrast of the playful process makes the calvary Abdi went through even starker. Racism in Dutch society is unavoidable for a Somalian immigrant, and it feels like one of the filmmaker’s goals is to highlight it. He does it in a cleverly conceived manner through the multi-layered style that always keeps the audience engaged.

Dijkstra’s films may seem like a combination of narrative simplicity and technical complexity, especially with his own presence in their worlds and on the screen, but they always resist classification. How do you decide if it’s a documentary, fiction, experimental, or animation film when it is made out of disparate and often contradictory elements? For programmers and critics, it’s a complicated and inspiring challenge, and for audiences, it’s an exhilarating and, in the filmmaker’s strongest moments, a fulfilling experience.

There are no comments yet, be the first!