Grow Up and Return

Immigration, identity and the feeling of home in short films in this years Go Short’s competition.

“Grow up and return,” says the 11 year-old boy Adil to the audience, but even more to encourage himself, as he leaves Morocco for France with his father and older brother in Saïd Hamich Benlarbi’s The Departure, screening in Go Short’s European Competition. The 25-minute fiction film is the perfect point of, well, departure, for this text that looks at several titles across the two international competition sections of the festival that deal with leaving home and coming back to it. Reasons to leave are different, but the results and consequences of the return all have one thing in common: resurfacing of the strong emotional bond that connects the characters to the places they grew up in, even if those places, and people populating them, were not necessarily a positive influence. Sometimes, they are destructive, at other times they are warm and fuzzy, often they are frustrating, but in each and every case, they have shaped who the person that is coming back has become as much, or more, than the place that they went to. Some of the films described here touch upon this complex and never fully solvable, entangled cluster of emotional influences.

At the end of The Departure and the beginning of his new life, Adil is yet to become this person. He is living with his mother and hanging out with friends from the neighbourhood, a normal boy’s life. The economic reasons that made his father and brother leave may be somewhat abstract for a small kid, but he feels the pain of his mother who has been left for another country and another person. When she gives advice to her youngest, she tells him her husband is now living with another woman, and that he has to pay respect to her. This scene lights up an early one, when the two men and the young woman arrive, and Adil’s mother and father act cold, almost as acquaintances rather than a married couple. What will the kid pick up from this, and how will it affect his future self and his relationships as an adult?

Thanks to Benlarbi’s precise script and controlled directing, we have the chance to picture the man Adil will return as. We can see his brother proud of his French wife that he undoubtedly sees as a trophy and confirmation of his status in Europe, and we understand the main conventions of North African culture and Islamic religion. We also learn that Adil is a big fan of Moroccan middle-distance runner Hicham El Guerrou who competes at his last Olympics, in 2004 when the film takes place. In his opening voice over narration, Adil tells us that “people have started leaving”. It’s not difficult to connect the dots, this comes instinctively as we are in the midst of a refugee crisis that the seeds of have been planted back then.

When Adil tells his friends that he will be coming back twice a year, one of the boys is surprised: “I don’t know any migrants that come back twice a year. They only come once, or once in two years,” to which Adil replies, “But I am not a migrant, I am a Moroccan.” We are aware that such purity can only be found in children and we are already lamenting all the things Adil will lose by the time he comes back. When one leaves their country as a young child, they are stripped of a strong, comfortable and comforting background to lean on, and only echoes of it remain — unless the person in question is part of a group that refuses to integrate, in which case they effectively lose their future. But Adil’s father says it clearly: “Your future is in France.”

Leaving one’s roots

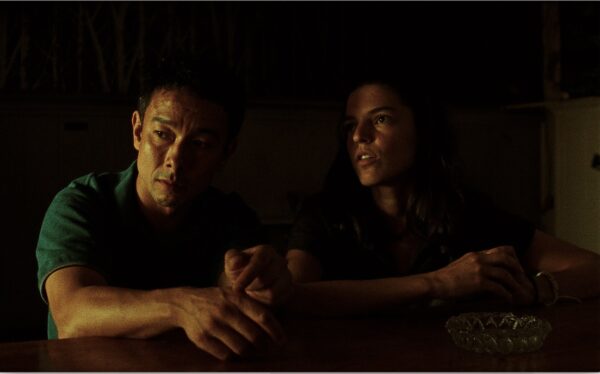

This background is what we commonly call roots, and some films in the programme take this in a very literal way. In Nha Mila by the Portuguese director Denise Fernandes, also screening in the European Competition, middle-aged Cape Verdean Salomé is on her way back home to visit her sick brother, for the first time in 14 years. At the Lisbon airport, she runs into Águeda who works there as a cleaning lady. She recognises the passive hero of the film from their childhood, but Salomé does not remember her. Still, she convinces her to come visit her, and one of the women in the house is just about to take a plant from a jar into a pot. “My little plant has taken root,” she says.

These characters have taken roots in Portugal themselves: a young woman is looking at photos from her childhood and not recognizing herself. They talk about how it took them time to adapt to the society, dressing in a bright, colourful style, not understanding the European way of putting clothes together. Throughout this scene that takes place around a table, in an apartment that’s as tasteful as their experience and means will allow, but in a neighbourhood that’s anything but, Salomé looks simultaneously happy and sad. The incredible actress who plays her, Yaya Correira, singlehandedly manages to encapsulate this bittersweet melancholy in which emotions constantly switch places and transform, creating new ones that we struggle to come up with words for. This is the default emotional state of an immigrant that they can try to supress, or mask, or replace with another, but which always stays as the fundament.

This tumultuous, never fully resolved state is what prevents people from leaving home in the first place. The truth is, no one wants to leave their town or country unless they have to: the narrative in which masses of people come from the East to Europe in order to reap the social benefits and steal jobs is just a right-wing, populistic spin with no basis in psychology or reality.

The Departure

But those lucky ones who do not have to leave and for whom this is a matter of choice are shown in Elsa Rosengren’s I Want to Return Return Return, produced at the Film and Television Academy Berlin and screening in Go Short’s Student Competition. One line from the film clearly shows the difference. Sitting in a bar, an old man tells his friend that his partner lives in Vienna, and he loves Vienna, but he cannot leave Berlin as his roots are there, even though Kreuzberg is not “his Kreuzberg” anymore.

This film, which feels like a docufiction hybrid, or at least has scenes with “real people”, like the one described above (even if this is actually a perfectly created “fake reality”), follows a Greek girl living in Berlin, and hanging out with other immigrants—who, in case of citizens of First World countries, are always called expats. In other sequences set in bars or beer gardens, three African men talk about languages, a man tells someone sitting across from him about happiness (we assume the person he is talking to is the hero of the film) and another guy translates it for her, to make sure she got everything… Rosengren creatively describes the immigrant experience in a non-direct, subtle way.

This method includes the visual style of the short as well. Even if it was not shot on film, it definitely looks like it, with the yellows, browns and greys of the neighbourhood, along with occasional patches of bright colours, standing out. One really feels as if they were in Kreuzberg thanks to the film’s inherent depth of field, implying that new impressions can shed a different light on old memories and transform them.

In the all-digital world that we live in, old technologies can be applied to evoke a feeling of times past. Until recently, we considered VHS footage to be the “new Super” in this sense, conveying nostalgia and reality in equal measure, just like home videos do. It seems that is time for 35mm film to take this place, in a new context and with new implications that we are yet to learn to employ and recognize: it will never be perceived as amateurish, which lent the aforementioned qualities to other formats, but it already feels like a movie shot on film has more to say, or that the director knows what they are doing and are using it with a particular purpose.

Home is people

Another short shot on film with a definite purpose, Still Life from the Academy of Media Arts Cologne, seems like it has been made by a master filmmaker and not a student. Latvia’s Anna Ansone evokes Tarkovsky in her visual style, and delivers a clear nod to Nostalgia in the story of Elina, a girl in her early twenties who returns to the family’s summer house after her grandmother has died. She is supposed to pack things up while she shows the place to prospective buyers.

The forest-set house is bucolic but also threatening, with echoes of horror tropes in the way that it is treated by the camera. At one point it takes the POV angle from outside at night, as Elina sits inside. It zooms in like in a slasher film, accompanied by the organ-driven music score, and when the very physical ghost of grandmother simply appears, Elina acts as if it’s just normal. And the viewer does not take this as implausible; in addition to Tarkovsky’s influence, Ansone has borrowed Bergman’s ease of introducing genre into poetic or philosophical cinema.

This is preceded by a call Elina has with her mother, where we understand that the dynamics between mother and daughter hail from the relationship mom had with grandma. Even though there are scenes that scream nostalgia, such as the time she spends in her old room with typical teenage posters, Still Life deals with family trauma and unresolved interpersonal issues, a huge psychological obstacle in the life of every person who grows up and leaves their home. Even if Elina lives in the same country, this temporal and physical break-up from a location that she ties memories and emotions to, makes it a lot harder to face these issues later on, quite possibly to never be dealt with. These matters poison the lives of everyone involved, with the heaviest toll on the youngest person.

Still Life

One filmmaker who has returned to face an old wound is Moldova’s Olga Lucovnicova in My Uncle Tudor. This almost unbelievably brave student documentary was produced through Doc Nomads and won the Golden Bear for best short film at the Berlinale. Olga comes back to the sun-bathed village house of her childhood, where her grandmother, while cleaning cherries in the lush, green garden, talks about how nature flourishes nowhere as it does in Moldova. This is another aspect of leaving—a different place may be richer or better to live in or even more beautiful, but we convince ourselves that nothing tastes and feels like home, often at our own expense. Again a matter of nostalgia, but in this case it also implies a dark side, and difficult and painful experiences from childhood are those that never truly leave us.

Olga has come back to deal with one such, devastating thing. The film opens in an idyllic key, with camera trained on memorable details that just become more beautiful in one’s memory as time passes, like a colourful caterpillar slowly making its way over the couch, but as the director suddenly sneaks her uncle Tudor into the film, these shots are replaced by more intimidating and symbolic ones. As she starts talking to him about what he did to her when she was nine years old, we already recognize where the story is heading, and we do not see any of the characters, but rather a succession of slightly disturbing images, such as a torn black plastic bag or a spider spinning its web around a fly.

The truth of the childhood trauma that Lucovnicova delivers calmly but with a trembling voice to her unphased uncle, who frankly seems to believe it wasn’t a big deal, is all the more devastating for the way it is introduced, and mixed with her positive memories of the place and the time. The way Olga’s grandmother and her sister (the uncle’s wife) act, as well as the man who looks like he could be his son, is additionally painful: it’s all joy and good memories and pride of the successful member of the family, becoming a true filmmaker out there in the big world. Of course, there is no secret buried as deeply as a family one that everyone is aware of but no one ever mentions.

In another brave and painful autobiographical documentary, but very different from Lucovnicova’s perfectly executed concept, This Day Won’t Last, screening in Go Short’s European Competition, Tunisian filmmaker Mouaad El Salem uses a collage of visual techniques to relate the experience of a gay man in the society in which homosexuality is banned by law. The filmmaker combines a digital camera and a smartphone, black-and-white photographs, some shots that are reminiscent of VHS, and even some underwater footage, and a voice over into a cry for help for the LGBTQ community in the country, but even more for himself. He relates the story of an old fig tree in his town that was uprooted from its original place to make way for a construction site, and moved to the garden of a luxury hotel. After a month, the tree died. This is what he is afraid will happen to him if he leaves his country, where in 25 years of his life he has not managed to achieve anything and where he often feels lonely and always oppressed.

This is the key to the immigration question. Many people leave their homes for more opportunities and promise of a better life, and this man is fighting to keep his very identity. Usually, it is exactly our identity that is endangered by such a move, but El Salem does not see a way to keep his by staying. The way such a situation tears a person apart is felt viscerally in this raw, technically bare-bone but thematically complex film.

With his painfully honest approach, the Tunisian director turns upside down the conventions of cinema, a perfect medium to describe emotions and states that cannot be put into words. Other filmmakers mentioned in this article use more orthodox methods to achieve the same goal, but all of them are scarred by their experiences or inspired by the scars of others, creating works that take them and the audiences through a cathartic process, which in turn explains these issues in a non-rational, instinctive way. The only way it can be done, really.

Mentioned Films

The Departure

Saïd Hamich Benlarbi, France, Morocco, 2020, 25’

Morocco, 2004. Adil, aged 11, spends the summer playing with his friends and waiting for his idol, Olympic runner Hicham El Guerrouj, to compete in his last Games. The arrival of his father and older brother from France for a few days will mark him forever.

Nha Mila

Denise Fernandes, Portugal, Switzerland, 2020, 18’

After 14 years away from her homeland, Salomé is forced to return to Cape Verde to see her dying brother. During her stopover at Lisbon airport, Águeda a cleaning lady recognizes Salomé as “Mila”, her childhood friend. Águeda invites Salomé to leave the airport and spend the stopover at her home, with the women of her family. The neighborhood transports her on a spiritual journey, whose destination unfurls a painful bond with her homeland.

I Want to Return Return Return

Elsa Rosengren, Germany, 2020, 32’

One late-summer morning in Wrangelkiez, Berlin, Elpi, a young Greek woman, receives a phone call from a long-lost friend. As the day progresses, Elpi’s apprehensive wait for their reunion interweaves with the lives of other local residents.

Still Life

Anna Ansone, Germany, Latvia, 2020, 22’

After her grandmother’s passing, Elina returns to the summer house of her childhood to show it to potential buyers and deal with all that is left behind. The visceral presence of the ghost of her grandmother forces her to reflect on the legacy of failing familial relations.

My Uncle Tudor

Olga Lucovnicova, Belgium, Portugal, 2021, 20’

After 20 years of silence, the filmmaker travels back to the home of her great-grandparents in Moldova, where she suffered a deep-rooted trauma.

This Day Won’t Last

Mouaad el Salem, Belgium, Tunisia, 2020, 25’

In this urgent diary film about longing for freedom and community, the filmmaker reflects on the individual yet collective experience of growing up queer in Tunisia today. Through personal videos and photographs, the film draws attention to the still-existing Article 230 brought by the French colonisers to criminalise homosexuality.