Home is Where it Hurts

Testimonies from Today’s War Zones at Vienna Shorts

Through the symbol of home, Vienna Shorts’ programme “When Will They Ever Learn? Testimonies from Today’s War Zones” ruminated on the scars of war trauma.

War erases the notion of home as much as its destruction obliterates the actual buildings housing residents, families, and strangers. Its blind cruelty takes lives away and dismantles relationships, leaving only the rubble of past safety behind: this is an everyday reality for people today with more than one hundred armed conflicts taking place around the world, according to the Geneva Academy of International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights. Because of or despite its proliferation, ‘war’ remains a catch-all term, and so does ‘war zone’; words we resort to in order to simplify and grasp the incommensurable pain of millions. Making (and screening) films of war is a necessity and a duty, despite the potential confines of language and empathy, as mediated through the screen.

This year’s Vienna Shorts embraced this limitation full-heartedly and proposed a set of five short films from Kosovo, Palestine, Lebanon, Ukraine, and Bosnia and Herzegovina, curated by Doris Bauer. A moral undertone was already embedded in the programme’s title, asking the rhetorical question (borrowing from Pete Seeger) of “When Will They Ever Learn?” to these film-testimonies. “When Will They Ever Learn? Testimonies from Today’s War Zones” ruminates on the scars of war trauma and survival—the two faces of one’s personal heavy load, the psychological burden of staying alive. But more importantly, the shorts chosen by Bauer speak about trauma through the symbol of home—be it a family house far enough from Beirut to hear, but not see the bombs, aerial footage of Palestinian lands that no longer exist, or a floor endlessly scrubbed by a woman whose PTSD manifests as compulsive cleaning.

Home is not only contested, it’s a source of hurt, a safe unity beyond reach. In trying to map a way back ‘home’, the films show that dislocation can be many different things, and so can a homecoming. Firstly, in I believe the portrait saved me (2025), Kosovan director Alban Muja films a testament masked as a story: the narrator and protagonist of that story being his own father, Skender. “Twenty-five years ago, when the war in Kosovo was raging…” is the film’s opening line, chewed and slowly spelled out with a couple of small pauses over the black screen. Then the first, rather peculiar image confronts us—a group of maybe thirty men occupy three rows of classroom desks, some are standing in the back of the room, but all are gazing ahead, to the storyteller we can’t yet see. But the counter-shot to that of the classroom audience is not of a person at all, it’s of a blackboard. On it, the film’s title, written in chalk.

Skender Muja was captured in Mitrovica while attempting to flee Kosovo in 1999, together with many other locals who were Albanian citizens, but what singled him out was his ability to read and write in Cyrillic. He himself narrates the story in the past tense, explaining how he was a painter and a school teacher before becoming a war captive. How his profession and, most of all, his dexterity, aided in his survival. How he managed to save his life by following an order: the order to draw a Serbian commander’s portrait.

I believe the portrait saved me is a reflective documentary with one major reenactment: the drawing of the portrait we witness in almost real time, while Skender recounts the experience as it happened. Trauma seeps through his hoarse voice, but his simple sentences are upheld by a narrative logic, as natural as the flick of his hand sketching the portrait. But before chalk lines even begin to resemble the face of a man, they screech. Skender’s chalk piece thuds and shrieks when marking the blackboard, yet the echo of it all is resoundingly calm. Whenever the short cuts to the other side of the room, the frame shows men his age and what we presume are their sons and grandsons, listening as his story unfolds. Unnatural stillness has gripped their faces, quite the opposite of what one associates with classroom chaos, as their witnessing doubles that of the audience, enlarging the film’s ethical scope. With this in mind, the still takes and careful framing of I believe the portrait saved me imply more than just preparation and staging, but in this case, it probably served as safeguarding. Like Abraham Bomba in Claude Lanzmann’s Holocaust epic Shoah, who found the memories of being a barber in the Treblinka camp coming back to him while cutting hair many years later—the body remembers.

I believe the portrait saved me (Alban Muja, 2025)

Kamal Aljafari proposes a more direct way of remembering with UNDR (2024), a film made up of archival material and mesmerising aerial footage of a people-less Palestine from up high, occasionally interrupted by ticking and explosions. The most experimental short of the five, UNDR comes (perhaps surprisingly) second after I believe the portrait saved me, to mark a shift as it counters the human narrator of Muja’s film. Aljafari, whose decade-long filmic practice upholds found footage as a (metaphorical) negative of the present, lets the helicopter-shot images speak for themselves. Deserts and ancient tombs are difficult to discern from war ruins and human intervention, but when the film cuts to people—be it farmers at work or children playing—the eeriness of that juxtaposition already singles them out as ghosts. That they are: ghosts in the machine of cinema, just as much as the caverns forever altered by dynamite and bombs.

Aerial shots are a way for cinema to assert its mechanical supremacy over life; it’s no surprise CCTV and satellite surveillance serve their masters thanks to the same principle of ‘looking down’ at the disadvantaged, the weak, the expendable. In UNDR’s aerial images, we see the violence that often accompanies the act of mapping, alluding to the grabby gaze of the occupier, the coloniser, the perpetrator. To that gaze, the ‘where’ and ‘what’ are not important, and in fact UNDR refuses to geographically locate its images—an act of defiance that can be read as a protective measure against further claims on the wartorn Palestinian land.

The festival website uses two tags to describe the “When Will They Ever Learn?” programme: “tough” and “touching”—words that seem rather vague, but when taken as sort of content warnings, they distill the conflicted sentiment arising in a viewer when they’re made witness to a personal story of war. As the only fiction short in the programme, 2006 (2024) by Gabriella Choueifaty invites a measured amount of suspicion as to how the realities of war might be filtered through the conventions of fiction filmmaking. Even when one clocks that 2006 reimagines a few days in the life of a family during the 34-day war between Israel and Lebanon and therefore links to UNDR both geographically and ideologically, it is a bit of an ask for a viewer to retreat into the (relative) comfort of narrative fiction. However, isn’t that what we—those living outside of war zones—are doing anyway? The jolt one feels when thrust back into the familiar realm of fiction can also be beneficial.

Choueifaty’s debut short itself doesn’t warrant such considerations; it is thoughtful and considerate in the ways it fictionalises a past personal to the Lebanese director. Somewhere in the mountains overlooking Beirut, birds chirp and pink roses bloom, while bombing sounds echo in the distance. On the TV, the news shows footage of the bombardments again and again, even though the programme detailing the war between Hezbollah and Israel is muted—silence hangs in the air as mother and daughter sit on the couch. Lebanon is under fire, and while their house is secluded, far enough from the city, the fragile notion of home is splitting with cracks. 2006 snapshots the moment right before it all falls to pieces, a summer forever marked by war.

Confined to their mountain home, 13-year-old Sariah, her older sister Nayla, and their mother try to go on as usual. Three women who reject the safety of home have no other choice but to be there for each other day after day, and they all have their own way of attempting an escape. The mother removes herself, unaccounted for, and drives out to the sea—naturally, this is seen as an act of betrayal, to which Nayla revolts and Sariah keeps quiet. A counterpoint to her explosive sister, Sariah remains unreadable for the whole of the film thanks to the actress’ excellent command of her body, causing her face to appear almost expressionless, so blank with fear that it hurts to look too closely. Her piercing green eyes are wide open, scanning for emotional shifts and physical cues of distress while the bombings echo in the distance. Like a blanket, silence sooner or later envelops every scene with a dual effect: on the one hand, it marks a temporary relief—the lack of bombs—but on the other hand, it weighs it down with the obvious lack of speech, of comforting words. What 2006 distills is an image of a family in pieces, but most importantly, it does it without showing (or even hinting at) a prior state of homeostasis. We’re left to wonder whether there ever was a ‘one big happy family’ home to begin with, but what’s certain is that after July 2006, there never will be.

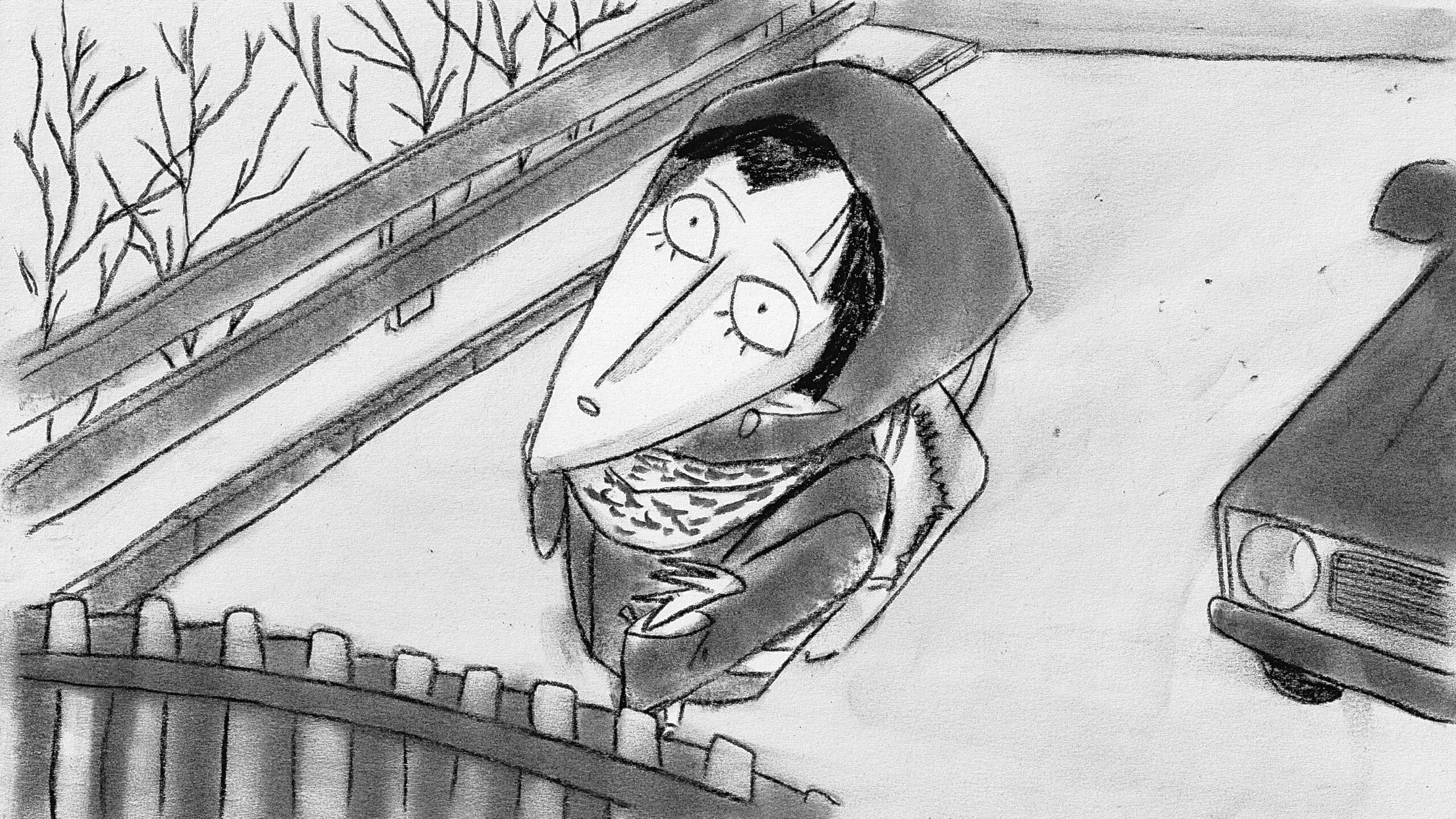

On 24 February 2022, like many others, Anastasiia Falileieva and her boyfriend left Kyiv for Irpin, believing that the house of his parents would provide more safety than the capital. With black and white sketches and shadows hanging above everything and everyone like toxic grey clouds, Falileiva’s animated short lays out the grim confession that lends the film its title, I Died in Irpin (2024). The first-person account colours the disturbing animation and the characters’ angular faces with dread and brutal honesty—beginning a story of survival with an admission of metaphorical death, conveys the depth of the wound.

I Died in Irpin (Anastasiia Falileieva, 2024)

I Died in Irpin carries the pains of a war refugee with a broken heart, outlining a strong bond that under pressure transforms into stifling codependency. In her narration, she admits the memories are distorted, and we see this in the parents’ portrayal—the mother’s head ballooning over her body and the father’s head the rectangular shape of a radio as they preside over the couple’s so-called safe harbour. Phlegmatic characters appear on a screen that pulsates with the hand-drawn shadows, detailing the cognitive dissonance at play. Even without the narration, the short would feel equally heavy as the animation is stripped from its beautifying elements—the rounder forms are rare and unstable, moulding into shapes and dissolving shortly after, while the human figures are sharply drawn: their hands are claw-like grasping at the little sanity they can find in days of incessant bombing and growing uncertainty.

For Falileieva, the significant other’s childhood house feels like an anti-home. A shrinking, suffocating place where someone else makes the rules, and she is forced to comply. Such confessions are only possible in hindsight, and the film’s present perspective oozes with pain and confusion over the past. People on the front line, she says in a low voice, don’t want to abandon their homes, regardless of the danger. Irpin, being one of the most intense frontline spots, exemplifies that dual nature of home—as both a sanctuary and a prison—even when it’s not your own.

At the beginning of Ceasefire (2025), its protagonist Hazira recalls being forced to leave her home behind and move to a refugee camp in Tuzla Canton, northeast Bosnia, nearly thirty years ago. Now, still in the Ježevac refugee camp, she has built a life around the idea that maybe she will never be able to return to her home village. We see her in the garden, overgrown with weeds that frustrate her, overpowering her attempts to look after the onion crop. In her demeanour, she’s open, talking to the camera as if it were a long-time friend. With striking ease, she switches from the topic of vegetable growth to swearing at her father, Ratko Mladić, and Radovan Karadžić—three men who, in different ways, have ruined her life. “Film all you want,” she says, obviously addressing director Jakob Krese, who also mans the camera, and asking after his wife and daughter. “A small circus,” is how Hazira describes her living situation, but nothing in the short film strikes us as worthy of such flamboyant description. If anything, the woman lives mostly alone, occasionally mentioning her son who lives abroad, and she spends her time doing chores and cleaning. The latter she does obsessively during many long takes, which she also talks over incessantly.

Hazira is a survivor of the Srebrenica massacre, and to this day, her home village falls under the jurisdiction of Republika Srpska, the Serbian part of Bosnia and Herzegovina. For political reasons, the return to a coveted home (and a state of purity) seems highly improbable. What Ceasefire shows is not a straightforward testimony—instead, the film makes space for the doubts, hesitant pauses, and non-linear ways traumatic memory works. Though fragmented, Hazira’s account of the Srebrenica massacre remains central to the film, and to her splintered character, visible in the admission that since the war ended, she can’t “sit still.” In her own way, without the crutches of a calm, intellectualised self-reflection some viewers may have learned to expect from such documentaries, Hazira manages to speak of a life in the tight grip of PTSD and emotional flashbacks, naming trauma as trauma. Krese is nothing but a supporting observer in the intimate (yet isolated) world of a survivor. That said, Hazira is a beguiling subject to behold and a draw for the camera, her rare charm exemplified in the flippant way she jumps from confessing “It’s strange that I’m still alive” to the triumphant cheer of “I’ll survive anything,” disregarding the worries for her being an ageing widow in a refugee settlement for twenty-nine years.

Hope shines through Hazira’s ironic optimism, and the same hope can be found in all five films in this programme. However, this is not the hope of someone projecting futures onto a better world. Losing one’s home is not the same as losing one’s life, but when identity, freedom, and independence are being stripped away from you, home becomes an impossible place. For many, this is a sordid reality, yet as these shorts show, home still somehow persists as an idea, even when the world crumbles. One could say it’s a necessary one to keep living. That is why all the films in the Vienna Shorts programme have one foot in the past and one foot in the present, whether it’s by way of reenactments, found footage, or recollections. War, like the trauma it incurs, is a split chronotope and a sudden eradication of safety, but one’s memories of it, however deep they rest under the debris, are those most valuable remains that can, perhaps, rebuild a home.