In the Dark Times, Will There Be Singing?

On Mourning Our Tomorrows

In Ren Scateni’s “Grieving Tomorrows” programme at this year’s Glasgow Short Film Festival, grief is framed as denied, fragmented, or fluid, and, most often, as a political act.

According to the recent World Happiness Report, Lithuanians are the happiest under-30s on the planet. However, there seems to be something rather peculiar about the supposed joy of Lithuania’s new generation. My hypothesis goes like this: our happiness can be best explained as a feeling of collapse in temporary suspension, ‘temporary’ being the key word here, meaning ‘enjoy it while it lasts’. And yet a sense of grief permeates our careless dolce vita: a grief for those already lost in Ukraine, a grief for our historically lost—or, rather, stolen by Russian imperialism—futures, a grief for the world we have built for ourselves since, and are now once again gradually losing.

In times like ours, cinema may become synonymous with blissful ignorance. So, here’s another theory: good curators are equally good listeners. To be more precise, good in a particular way that therapists are able to register not only what is being said but what remains hidden. Looking at this year’s Glasgow Short Film Festival’s programme from this angle raises little question as to why the festival’s newly appointed programmer Ren Scateni decided to dedicate three screening programmes to “Grieving Tomorrows”: when the news seem to be solely generating material for dystopian literature, we might prefer to take a detour—and yet the curator is here to remind us that the only way out is, unfortunately, through.

But is this supposed to mean that the cinema’s seat is simply an iteration of a psychoanalyst’s couch? While great at locating and addressing trauma within our individual histories, therapy more often than not becomes helpless when confronted with an existential angst stemming from history at large, be it the global rise of techno-fascism or a genocide unfolding in real time. In this case, depersonalised, collective forms of activism might seem like a more suitable ‘fix’—and yet, cinema hardly falls into that category either. The black box occupies an ambiguous space in-between: between the collective and the individual, the introspective and the outward-looking. So what exactly can moving images offer us in the dark times?

“As if to Die with No Name or Face”—part two of Scateni’s programme, framing mourning as a political and ethical act—includes Indonesian director Riar Rizaldi’s short Larung (2024), where fishermen perform a traditional sea burial for their dead comrade. The film is shot as a Malay-pop music video and exists in a strange, pastel-coloured limbo state between reality and afterlife, where its three ghost-like protagonists find themselves in complete possession of the fourth one’s body, engaging it in rituals so it can be transported to the other side. Similarly to the deceased fisherman, the moment we come to terms with the all-consuming inescapability of loss, our bodies become metaphorically possessed by grief—and in order to transcend it, we might need the helping hand of rituals, too.

The movie theatre began its life in times when the importance of rituals was gradually diminishing against the backdrop of modern urban life. And yet, perhaps precisely because of that, there seems to be something intuitive about using the cinema-going experience as a substitute for a practice that can hold our grief. If one looks long enough, the contours of their overlap begin to emerge: the relief of being allowed to cry in public, the experience of non-verbal togetherness, time emptied of productivity, the visual spectacle of the rite of passage. And, most of all, the promise of being changed, both by mourning and the moving images.

Larung (Riar Rizaldi, 2024)

While it can certainly feel privileged, indulgent even, to be experiencing grief in the context of the festival circuit, there is something quite radical about it too. As proposed by the curator in the programme’s introductory text, grieving can indeed become a form of resistance against the dominant narratives, as it goes on to teach us lessons about the beauty of sorrow in a culture of hyper-positivity, the value of processes that do not produce any tangible results and are impossible to ‘optimise’ or the trust in the journey and those we share it with, even when it seems like we will never reach our Ithaca.

In the early 1900s, French ethnographer Arnold van Gennep was researching rites of passage around the globe and came to the conclusion that all rituals seem to follow the same structure of death, followed by liminality, and then rebirth. “Grieving Tomorrows” could be seen as formally reflecting a similar arc, while thematically looking at such progression in relation to our connectedness to others. In moving from separation to oneness, it invites us to reframe loss not as something that creates a gap between us but rather as something that offers us a possibility for a different togetherness—after all, grief is love, inverted, and so the thing that made us ‘sick’ in the first place might be what can eventually heal us, too.

The first instalment of the series, “Discourses on Ontology, or Resisting Erasure”, stages a conversation between four films united by the feeling we plunge ourselves into at the earliest stages of grief: denial. The desire and impossibility to escape our circumstances, which permeate the shorts, are perhaps best encapsulated by a line from Angelo Madsen’s barraged tampon-inspired spiralling into trans mourning, The Source Is a Hole (2017). In it, the film’s narrator asks us if one should drink from the river of oblivion, so as to forget one’s past lives. Would we take a sip if it could at last calm down, in the words of Audre Lorde, “the entrails of Uranus, where the restless oceans pound”?

The feeling of searching for a way out while lost at inner sea seems to be a rather universal one, and yet the selection reminds us that there is something quite particular about it, too. Just as Esther Valiquettes’ portrait of an AIDS survivor Le recit d’a (1990) cuts from skin to the sandy emptiness of the Death Valley, the film exposes the isolation and, therefore, loneliness that sits at heart of the queer experience in a world that tries to erase its every trace. In the programme, even brief glimpses of connection feel restricted to the safe but secluded spaces the characters create for themselves. And yet, as in Sarnt Utamachote’s collective farewell to friends lost due to drug abuse in Berlin’s queer nightlife scene (I Don’t Want to Be Just a Memory (2024)), utopia might turn out to be just another dystopia in disguise.

“Grieving Tomorrows” then carries on with five films that dissolve the boundaries between the past and the present, between what is real and what is only imag(in)ed. In Chikako Yamashiro’s Your Voice Came Out Through My Throat (2009), a young woman lip-syncs the stories of men who survived the World War II Okinawa battle, her voice ‘hijacked’ by those who came before her, their pain now intertwined. By focusing on the body, the shorts propose to see it as a vessel that carries the ghostly presence of generational trauma. The lineage of ghosts we carry inside us makes our identities—and, equally, our grief—liminal, fluid, and fragmented, acting as a reminder that the one who is ‘possessed’ by history can never be truly alone.

I Don’t Want to Be Just a Memory (Sarnt Utamachote, 2024)

Lastly, the programme zooms out of the isolated mind and the possessed body to conclude with “Deep into the Ground, Our Roots”, an epilogue that walks us through the scarred, grieving landscapes of Beirut, Patagonia, and the Sahara. The films’ unhurried, dream-like feel appears like a fitting ending, both tonally and conceptually, that finishes the cycle of mourning at its last stop, acceptance. And yet acceptance does not denote resignation—while dissecting the ties between economic progress and the collapse of pretty much everything else, the films quietly reject the proposal to drink from the river of forgetting. Their landscapes are ripe with memory and suffering—not only that of humans who have inhabited it throughout the years, but of the land itself that still hurts and still remembers.

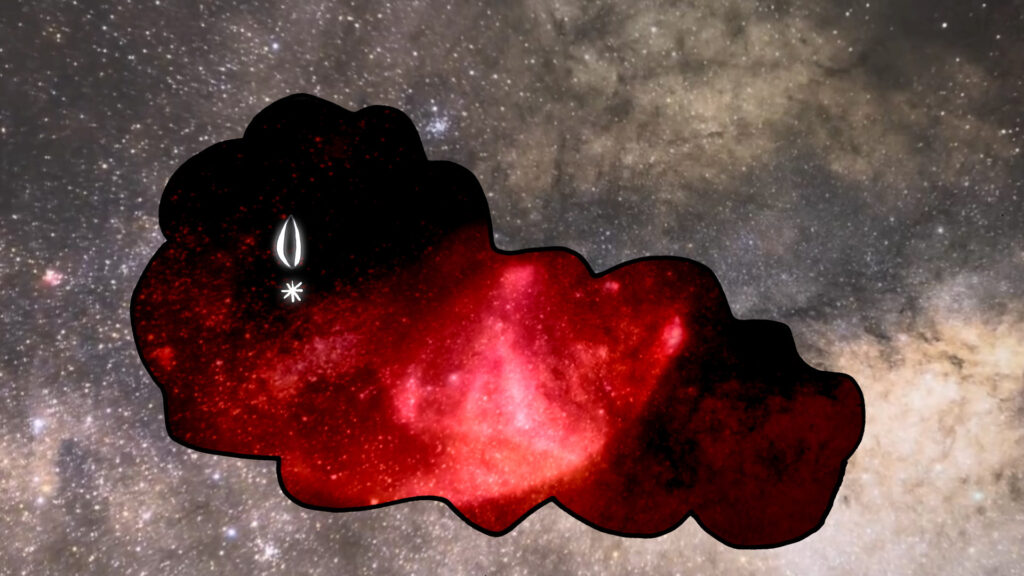

In the last film of the selection, Arwa Aburawa’s and Turab Shah’s And Still, It Remains (2023), the inhabitants of a village in Algeria’s Southern Sahara are reflecting on how their lives were affected by France’s nuclear missiles testing. Their home, which had survived a man-made apocalypse, however, is never framed as a dangerous, toxic wasteland. Visually, it is tenderness that permeates the frame instead: the land is sun-soaked and coloured in soft pastels, the people embraced and sheltered by it. Softness here becomes a form of resistance, telling us there are ties so strong even the colonial conquest cannot sever them; that, despite everything, the people will remain to both live and grieve for their land, and the land will carry on living and grieving for its people.

After completing the cycle of death, liminality and birth; after sitting in a dark room full of strangers; after engaging in a practice that slows down time by allowing us to sink deeper into our personal and collective mourning, one might feel propelled to return to the beginning in order to yet again ask: so what exactly is the purpose of grief—and, in turn, that of cinema? While the experience of loss can certainly feel like drowning in a restless, pounding ocean, perhaps grief invites us to take one last breath, reach the depths of our feelings, and come back to the surface, transformed. Come back—and then carry on living, even in the times that are getting dark. Or, in the words of Bertold Brecht, written around the time the anti-Nazi playwright was being exiled from his native Germany in 1939:

In the dark times

Will there be singing?

There will be singing

Of the dark times.