Inside My Head

Mohamed Bourouissa’s Genealogy of Violence

Now nominated for Talking Shorts’ New Critics & New Audiences Award 2026, Mohamed Bourouissa’s compelling Genealogy of Violence visualises everyday racism.

Genealogy of Violence, awarded the Grand Prize at Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur, opens on the aerial view of a suburb late at night. It is immediately disarming: we (the camera and the audience) are very, very far above the ground; there is a budding feeling, something we cannot place yet. Up here, the candor of the short’s opening narration startles us: “When I met her, I was an intern at GDF Suisse. Basically, I’d go to Paris to pick up equipment and install smoke detectors”—it begins like this. The voice (which we later learn belongs to the protagonist) goes on to describe a first encounter with the girl who would later become his partner. The specificity that is invoked suggests real memory: this will be confirmed to us in the closing credits when we see that director Mohamed Bourouissa based this film on the personal story of a friend.

There’s that uncanny feeling again as the shot changes to one of an impossibly moonlit city sky. We realise what we’re looking at might not be simple drone shots but perhaps digitally modified versions of all above and below (landscape/nightscape/cityscape). Another shot: now we’re on the road level, observing a street laden with houses on both sides: the perfectly identical street lamps, the half-invisible, wire-framed cars not fully rendered. A digital plateau: we understand these landscapes to be some kind of diorama. Why? The music presses down hard, a warning of metallic, foreboding beauty as the off-screen story continues: the boy asks for the girl’s number, she jokingly refuses, then passes with him through the subway gate, skipping the fare. “A fare skipper and you won’t even give me your number?”, he jokes. They laugh together. With her, he will come to feel like he can be himself, seen as the person he aspires to be, the voice tells us. It is a sweet story, and yet we are now in a CG-enhanced square, a single car planted under a purple-lit tree. There is a strange dissonance between these things. The narrator finishes up: “I’d just gotten my licence. I was 21, happy. I was a free man.” A hand lowers the volume of the radio, pushing the very audible soundtrack underground, priming it to return with a vengeance soon enough: something is going to happen.

Genealogy of Violence is about a police search. This is what happens to our protagonist, interrupting an intimate moment. Until then, the couple share a gentle dialogue that owes its beauty to the sincere, understated performances of Bilel Chegrani and Nina Zem. Their tranquil treatment of each other and kind smiles form a dome inside the car, a safe place: notice how the filmed image is, for the first time, real, unaltered. The subject of having kids comes up, and our protagonist gushes about it, proclaiming the paramount importance of love when raising a child. If they had one, would he move to the US with her? “If we ever had a kid, I’d run a really tight ship,” he tells her, the 21-year-old dreaming of responsibility. They share liquid, bubbly laughs. God’s will also comes up in the conversation. And then, a bright white light flashes through the window.

Everything seems to slow to a crawl; the music ramps up, sinister, and the world goes into slow-motion. “At that point, I stopped listening. I switched to autopilot like my body was no longer mine”. Genealogy of Violence, we understand finally, is about a dissociation, an escape of the mind when it is not possible to escape with the body, to do so into unreality if need be. The voice quietens, giving way to the soundtrack as Chegrani hands his ID to the officers—and we are taken by the camera into his coat, flying into the ridges of the material, and then to the bloodstream inside of his arm. Nina is watching from the passenger seat as her boyfriend is asked to lean against the hood and is patted down: as if he himself, at least psychologically, is no longer present.

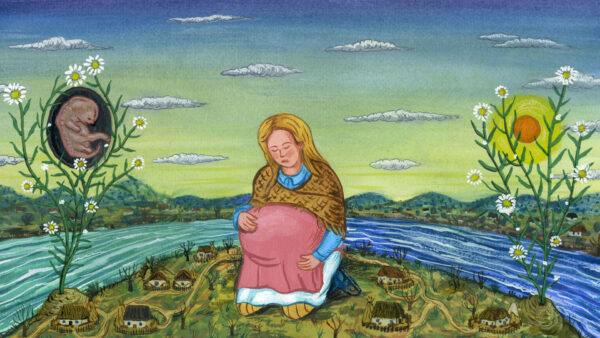

Généalogie de la Violence (Mohamed Bourouissa, 2024)

What follows in the film is a moment of pure thought, an instant stretched into eternity: the protagonist starts telling us about a nightmare he had as a child, of a pit bull that was always watching from an unbridgeable distance. The camera shows us an impossible thing to behold: the neurons firing inside his brain, transforming into burning nebulas, galaxies shaped like a dog’s head, landscapes, blazing canyons: a topography of the mind. At the end of the dream—the narration continues—the dog was now a swirling, blinding sun that the remembered child could no longer stare at. Bourouissa shows us all of this through 3D art, generated video, spatial scans, and other kinds of special effects: we travel up Chegrani’s body, around and inside his face, back into the cosmos. At a point before the end, in the diorama of the suburban square, frozen in time, the film shows us a figure watching from a window, and then another figure resting in the bed of that house. It is a moment from the very eye of God—the watcher that is watching the person watching: vectors, gazes, all in a single instant. Some kind of God could see all of this take place at the same time, every atom at once: Chegrani’s tracksuit coat, his girlfriend’s fingernails, the armor on the policemen’s chest. A God like that could perhaps decide their fate.

Bourouissa’s aesthetic thesis is very strong: the unjust, racially motivated search is a literal interruption of our protagonist’s life, a gap in time, at their mercy, a dissociation. Just as much as the real image, the “real life” of the film dissociates from the fabricated, digital world of conscience that we now understand is the camera that first saw it all from the sky: the bird’s eye view, the mind’s eye, the total conscience, water droplets on the car, erythrocytes in the artery… There is thankfully the understanding mercy of her eyes. The search is humiliating and emasculating: remember how he was just talking about being a rock-solid provider for their family (“A bit of bragging?” Nina then asked, smiling). She moves her legs away from the glove compartment, rigid, as the policeman gets the documents for the vehicle, then moves them back and closes the door. There is nothing to do except wait for it to end. After everything checks out, the two policemen leave, and the anonymous spectator at the window of the nearest house, presumably, returns to bed, the possibilities suspended, the dog’s gaping maw dormant once more. Life seems to resume. “Are you alright?” Nina asks. We don’t get a clear answer. Like Radiohead once said, from inside a car not much unlike this one—for a moment there, we lost ourselves.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #6—a tandem workshop held at Kortfilmfestival Leuven and the Vilnius Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

Genealogy of Violence was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2026 at Filmfest Dresden by Ana Jiménez, Lan Mi Lê, Marian Freistühler, Regina Campos Ccarhuarupay, Sadaf Biglari, and Sara Simic, the participants of the European Workshop for New Curators #1.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism, the European Workshop for New Curators, and the New Critics & New Audiences Award are projects co-produced by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme, and in collaboration with This Is Short.

Image Credits: Mohamed Bourouissa, Généalogie de la Violence [Still], Vidéo (couleur, son), 15’, 2024 © Mohamed Bourouissa ADAGP, DIVISION. Production : DIVISION et Studio Mohamed Bourouissa. Avec le soutien du CNC, de ARTE France, de Mennour, Paris, BLUM Los Angeles et du Palais de Tokyo.