I’ve Found Myself: I Am Another

The Nostalgia Found In Archival Footage

Concorto Film Festival’s MNEMOSYNE cycle aptly summarised contemporary trends in found footage filmmaking. Shorts from different cultural contexts incited viewers to wonder which spaces have been allowed to become subjects for nostalgia and which have not.

Archival footage is most often an invitation to project. Stripped bare from a context, dislocated from its historical space, found footage tells us less about its own past than about our current times and own subjective truths. “That my voice is the adult voice of this child, should not stop you from imagining these subjects as blank images for you to project your values to,” claims a narrator in Clemens Poole’s Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro. Glory to the Heroes. Forgotten histories, escaped meanings, and shy hints of something that once used to exist all turn us into eager private investigators trying to fill in the pieces of a story we don’t know. Found footage is yet another canvas for us to lay our fantasies onto. But in all of it, there’s an inescapable sense of nostalgia. We try to connect with these images of the past as if they were of people we know, we search for kinship, we so very often see ourselves.

Once, the use of archives in a film might have denoted some illustration of scientific credibility or proof of historical existence. Although, it begs the question of whether a film like Esfir Shub’s The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty, one of the first-ever examples of found-footage practice, wasn’t also a display of subjectivity. The way archival footage is used in current filmmaking usually subscribes more to an emotional space, with the idea of ‘found footage’ stretching to include personal or amateur archives as essential sources and modes of filmmaking. Take a film like Agustina Comedi’s Silence Is A Falling Body, where a daughter tries to understand or, rather, discover her father’s life through the videotapes he’s left behind.

Because they deal with memory and affect rather than with fact and history, one of the main tendencies in found footage films recently has been to articulate a portrait or a self-portrait; aside from personal archives, images of others are also commonly used to talk about a self, be it a real one, a (self)fictionalised one or that of someone close to a certain “narrator” or “I”. If there is something that ties together most of the audiovisual objects in Concorto Film Festival’s MNEMOSYNE cycle, it is an inner voice that meditates, remembers, longs for something now lost, or outright invents new histories and realities.

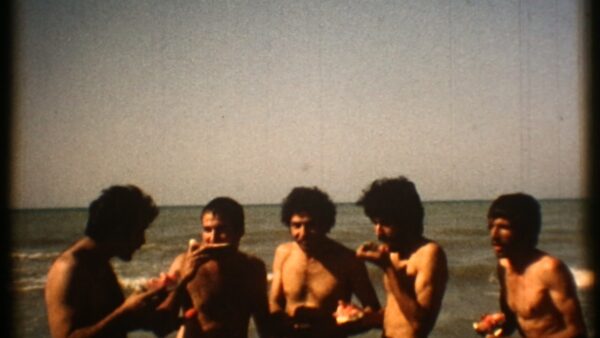

Inspired by a 1989 short story of the same title by Gregory Burnham and by Édouard Levé’s “Autoportrait”, Mohammadreza Farzad’s Subtotals is one very apt example of this strategy of reappropriation, by reworking 8mm home movies from Iran into an account of someone’s life laid out as a poetic sum of statistics. The effect is profound, but the technique simple. The film searches for nostalgic similarities, common realities, or clues in these found images that might be further extrapolated into a personal story. Yet, is the voice talking to us that of a real person? Does a first-person narration mean we’re dealing with something autobiographical? Or, rather, is this a genie of collective memory?

Subtotals speculates on the universalities of human life—birth, childhood, failed relationships, grey hairs, number of dogs owned, and so on—evoking a sense of kindred reality that we’ve all gone through, one that has changed little over the ages, and a past we’d all, bittersweetly, like to return to. That is, in a way, the beauty of the home movie, which is most often appropriated by the found footage film: a nuance of familiarity that transcends the individual destiny recorded by the film camera. In other words, the banalities of personal archives bring us together because we can recognise in them the banalities of our own lives.

Subtotals (Mohammadreza Farzad, 2022)

However, with found footage, beyond an emotional link, this act of projection can also be one of subversion. Sometimes, it is political, as Akosua Adoma Owusu’s White Afro shows by recontextualising images from an educational film on how to style an afro on white women. At other times, this subversion takes on a simpler, comical effect. Almost in the style of a detournement, Isabelle Prim’s Condition d’élévation constructs a story from the archives of the French National Centre for Space Studies that is hilarious simply because the narrative has nothing to do with the intended meaning of the images. In Prim’s film, utilitarian footage becomes fiction, and scientific research becomes a visual aesthetic. This trend in found footage filmmaking almost acts like a commentary on the ease with which an image can change meaning—something both funny and potentially dangerous.

In a similar absurd fashion, Eugenia Bakurin’s Long Time No Techno extracts fragments from the archive of the Odessa Film Studio and adds a soundtrack that mixes techno beats and oriental influences. What we expect these images to mean and what they’ve come to seem like two such different notions that the incompatibility becomes funny. There is also an underlying contradiction to this video essay: something feels suspicious about this montage of happy people engaged in a perpetual dance. Surely, things couldn’t have been as cheery back then. This is a past as an illusion, an inflated image of the past that is over-romanticised and over-nostalgic.

While Long Time No Techno goes beyond a simple glueing together of music and images, it is worth noting that found footage has become a favourite and trendy illustration for music videos nowadays. In the Concorto programme, Stefano P. Testa’s Persiamia verges on this territory of aesthetic illustration, engaging with its archival material mainly formally by re-editing the images to fit the song While rhythmic and spectacular (it shows an old circus performance), the archive here is primarily used as a novelty backdrop for the music. Found footage is, indeed, the perfect blank canvas, the new ready-made.

When operating dialectically with the music, it can be used to create comical effects, or, if needed, it can further sustain or enhance the nostalgic tone already present in the music. Recently, this has gone beyond the appropriation of pre-existing material; it is becoming very common for music videos to try and emulate a found footage aesthetic, to incite the same feelings that something from the past might induce. The ‘video’ in ‘music video’ also goes very well with the idea of the video camera, which makes this kind of footage even more appealing in a context of retro and technology fetishes that have recently become very fashionable.

Today, technology and nostalgia are inherently tied together. What we look for in images of the past are not only sentiments that we recognise but also the markers of different media that we once used to interact with: we are nostalgic for aspect ratios, image quality, or interfaces. The Super 8 aesthetic or that of a VHS cassette have now become time capsules, instantly transporting back to a certain period in the past by recreating media-specific characteristics that we’ll remember from our youth. But these technological characteristics don’t always have much to do with the physical media. There’s a filter for everything you can now just slap onto an image to make it “look cool”. Nostalgia is, often, just a look.

As much as nostalgia may be a perfectly human inclination, it’s also a constructed product appealing to our need to reconnect with and dream about the past. Nostalgia is a malleable idea that reacts differently in various economic, political, and cultural contexts. It also changes with geographical space, as we can extrapolate from Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro. Glory to the Heroes’ and Long Time No Techno. Both films use found footage from Eastern Europe, namely footage from Ukrainian archives that belong to two profoundly different times.

Indeed, cinema has cast a nostalgic gaze on some geographies more than on others. The self-reflexive narrator in Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro. Glory to the Heroes remarks that the film’s story is actually one that an American filmmaker has projected onto footage of his childhood: “Western values that favour a certain vision of what my culture should be”. In this confrontation between the East and the West, nostalgia operates in two very different modes: the East is a space that hasn’t been allowed much self-romanticisation, whereas the West—even more so the West understood as a space dominated by America’s cultural exports—has built a culture of nostalgia. From the period drama to the biopic or the coming-of-age film, nostalgia is the great selling point of Hollywood genre filmmaking.

Long Time No Techno (Eugenia Bakurin, 2022)

The visual landscape in Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro is one that generally hasn’t incited romanticisation or emotional appropriation—what could be romantic about brutalist state-built apartments is an idea that many Eastern European children of my generation were brought up thinking. Born in 90s Romania, I’ve often found that our post-socialist desire to celebrate the past was minimal, mainly out of some hatred for the ‘local’ and an avid hunger for everything that was ‘Western’, which we’ve previously been deprived of. My generation, and the previous one, grew up on a blind consumption dominated by US blockbuster films and reruns of ‘Dallas’, which may have got us accustomed to dreaming and reminiscing about the geographical spaces of Western media and rarely about our own. We were all more enamoured with the picket fences and prairies of ‘Lassie’ than with what our own relatives in the countryside could offer. In turn, Western media never really had the proper tools —or the desire—to accurately represent the spaces of Eastern Europe as anything other than the “politically complex cold place”. Even if, at both ends, perceptions are now changing, Eastern Europe, romance and nostalgia have been very rarely perceived as compatible notions—perhaps only Jonas Mekas may have given us a well-sought-after glimpse through his images of his native Lithuania (see Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania, 1972).

This geographical space, both urban and rural, is currently being reclaimed, however, and not only through regional filmmakers who employ personal archives and discuss personal histories (see a film like Karla Crnčević’s Wild Flowers or Andra Tarara’s Us Against Us). Mainstream means like TikTok montages of found pictures are also nostalgic for a #EasternEuropeanChildhood as something pure and beautiful for all its lack and paucity. This mode of nostalgia contrasts with what would generally be described as a mainstream Western mode, where what is celebrated about the past is rarely hardship and, most commonly, the sweeter, more innocent moments in life. Most of these recent Eastern European acts of reclaiming, however, tend to refer to a post-socialist context, characterised, especially in the 90s, by the proliferated use of video cameras, and rarely go back to a time during socialism, possibly because of a conundrum that is hard to answer—to what extent can you afford to be nostalgic for the past of a totalitarian regime?

The two vastly different time frames put forward by the footage from Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro (the transition period) and Long Time No Techno (the socialist period) also underline a difference between the private and the public. Long Time No Tehcno’s images come from a film studio, which, as within most of the Eastern Bloc, fell under the jurisdiction of the state. This means these images validate an official aesthetic, an inflated and carefully curated representation of society. The aesthetics of socialist realism, in this context, usually never had anything to do with a past, nor with an actual present, but rather with an idealised future where communism would have been fully accomplished. It could be said that socialist realism was, in a way, nostalgic for the future—an existing tone that resonates with Eugenia Bakurin’s decision to, fittingly, add techno music over the images she uses. In contrast, Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro’s footage consists of images that were once private. Most importantly, they are private images from the 90s, when the idea of ‘private’, in an anthropological, political, and economic sense, became a concrete reality after the regime change.

The private, the public, and nostalgia are also essential notions that engage with the home movie as a prime material of the found footage film. The home video is generally understood as a leisure activity—an amateur endeavour as opposed to a professional one. That has made it a very fertile ground for evoking nostalgia. Anybody, so to speak, can be an amateur, a circumstance which breeds the kind of familiarity mentioned above with Subtotals. But, just like nostalgia, leisure is also a mutable concept. In Eastern socialist regimes, leisure was seen as an extension of labour. Even if certain states of the Bloc encouraged workers to join filmmaking clubs (see perhaps Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Camera Buff, 1979), whatever was filmed was understood as an appendage to their status as workers and citizens. In (Western) capitalism, leisure has been understood as a reward or escape from labour, a time dedicated to privacy, where an individual more or less retreats from the public and spends time at home, with the family. Leisure is time for the self.

There is one specific scene in Mad Men that I’ve always found to be the greatest illustration of Western capitalism’s relationship with nostalgia. Somewhere in the first season, advertising genius Don Draper is asked to sell a Kodak carousel to an audience. Bringing together some personal pictures of his family’s major life events, what he sells is exactly nostalgia, and the idea of it as an essential component of the American dream and the Western way of life. I personally never cared for that scene as a moving moment where Draper reflects on his life but as a transparent observation of nostalgia as a construct and a keyword of consumerism.

Nostalgia can also be a commodity, sold to us via tools, via aesthetics, reeling us in with the fuzzy feelings of familiarity and the promise to reminisce about the past. In current times, when the obsession for the retro has become rampant, we must ask ourselves when is nostalgia a pretty aesthetic we’re happy to consume and when is it a connection between humans that transcends time?

Mentioned Films

Subtotals

Mohammadreza Farza, Poland, Germany, 2022, 15’

An essay film compiled from Iranian 8mm home movies. A meditation on the uncertainties of a life that doesn’t hand you any bills.

Long Time No Techno

Eugenia Bakurin, Germany, Ukraine, 2022, 4’

The video features dancing moments from children’s films of the 70s and 80s, which provide a glimpse into a carefree time of adventure, fantasy trips, and freedom. These scenes serve as illusions of a time that has since passed.

Dima, Dmitry, Dmytro. Glory to the Heroes

Clemens Poole, Ukraine, 2021, 23’

Using a home video cassette that was shot during the nineties in Lugansk, a city now under Russian occupation, Clemens Poole creates a fictional protagonist onto which he projects an idealized narrative – but his character resists it and fights back.