Keep Filming

Palestinian Short Films Towards Liberation

Palestinian filmmakers often not only put their work on the line, but also risk their lives, channeling grief and hope through moving images. Against an ideology of denial, each film becomes a valuable historical monument.

For its 17th edition, the Glasgow Short Film Festival connected diverse forms of resistance that currently shape our political landscape. Across the four-part programme “Towards Liberation”, cinematic styles and narratives from around the world found themselves in dialogue, but one resilient part seemed most urgent. “Weapons of Criticism and Dedicated Consciousness” featured six Palestinian short films addressing the systematic, historically rooted experiences of displacement and dispossession. Roaming through key themes and moments in national history, the programme bears witness to the lineage of violence perpetuated by the Israeli occupation to this day. Yet the very existence of these films demonstrates the belief, resistance, and determination with which Palestinians carry on battling for their identity, freedom, and, most importantly, their lives. Additionally, the festival donated 50% of the screening’s ticket sales to Medical Aid for Palestinians.

Against an ideology of denial, each film in this programme is a valuable historical monument. Forged with creative and challenging forms, they stand firm, facing past, future, and present, needing to be seen, heard, and preserved more than ever. Among them, Mahdi Fleifel’s I Signed the Petition arguably resonates the most with our current failures to actively engage with the Palestinian struggle and to halt an extreme level of destruction happening right before our eyes.

The film sees Fleifel himself call a fellow compatriot and plan to petition Radiohead against the band’s upcoming concert in Israel. With the camera pacing the room restlessly, we can sense an artist at a loss, stuck in the prison of his own mind. I Signed the Petition shows complex feelings: a degree of regret for signing the petition and fear of discrimination, yet even the mere idea of rejecting the act provokes guilt as though ignoring the Palestinian struggle itself. Given the prevailing sense of powerlessness within cultural and artistic institutions in their current state, the questions Fleifel asks in the film and how he asks them—with desperation in his voice and the uncertainty in his silence—feel all too familiar.

Since Israeli forces started a genocidal attack on Gaza in October 2023, online petitions have become symbols of our heartfelt yet vain attempts to denounce genocide and the silent political or cultural structures that are complicit. Far from being irrational, Fleifel exposes a very reasonable fear, considering the number of artists who have been targeted and subsequently censored. Yet at the same time, Fleifel challenges his own capacity for action and agency, and by extension, those of his art. In the film, Fleifel’s friend Faris eloquently analyses the mechanics of disempowerment: “The cultural power play that Israel has put forward and that most of the dominant Western societies have been fed with is so entrenched that it’s difficult for us to overturn.” Upon hearing his words, one can’t help but question why we keep signing petitions or making art if such efforts will never be enough to stop the genocide, let alone save a life. Or should we consider that our efforts are actually directed at ourselves, easing our conscience that we did the right thing?

The dialogue between the filmmaker and his friend alludes to a moral and political dilemma: there are many layers to the paradox Palestinian artists find themselves in regarding their identities. “You’re not some French guy who grew up in the south of France making films about sex in the lavender fields, who’s got the luxury of thinking about himself in the third person,” continues Faris. For Palestinian artists, national identity can be both the key and the prison itself. How can one tell a carefree coming-of-age story in a place where children are killed more than elsewhere in the world? How can one make slice-of-life dramas when people struggle to survive on a daily basis?

In this respect, Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind’s In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain is an unusual example, daring to explore imaginary futures that go beyond Palestine’s current political paradigms. Most documentaries about the region prioritise live footage, archival materials, and interviews that speak to the constant need to justify the legitimacy of their struggle. Sansour and Lind, on the other hand, filter their vision through the aesthetics and tropes of the science-fiction genre and analyse the underlying processes that shape history. Theirs is an epistemological quest for myth- and history-making.

The film imagines “a narrative resistance group” that seeks to manipulate history by hiding lavish porcelains underground for a future fictitious civilisation who, when the time comes, will be able to prove their ownership of the land. Here, Israel’s exploitation and appropriation of archaeology to lay claim to Palestinian lands become the key to understanding what this convoluted story really implies. Sansour and Lind largely rely on allusions in their storytelling, and on high-contrast, otherworldly, computer-generated images. The imaginary reversal in the historical narrative—making the Palestinians the “narrative terrorists” of the future—imbues a certain level of irony and humour. In the Future self-reflexively draws attention to how images and sounds can be manipulated through the lens of politico-religious ideologies such as Zionism, demystifying the cult of evidence and veracity in image-making processes.

In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain (Larissa Sansour, Søren Lind, 2015)

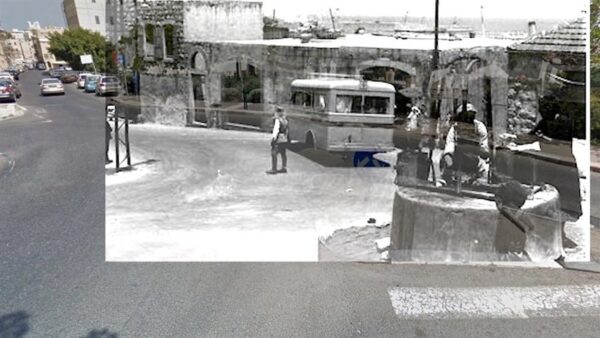

The shortcomings of archival material can also be traced in Razan AlSalah’s Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, And So Was The Nakba. If one has to deal with historical and cultural memory that is (to be) erased, it’s a common practice to convey archival material to virtually restitute what is lost. But within the Palestinian context, more than common is a kind of archive deprived of national histories prior to the Israeli occupation: an archive of dispossession where people were not only forced to abandon their lands but also robbed of their memories, identities, and even the language they spoke. It then begs the question: to what extent can we grasp the present condition if we take a broken or stolen past as our vantage point? AlSalah offers a unique understanding of this dilemma by positioning themselves in the present, where all traces of the Palestinian past—buildings, streets, and the people—are systematically being wiped out.

AlSalah reimagines the past through Google Street View when an old Palestinian woman virtually revisits the Haifa streets of her childhood. But the people and places from her memory are nowhere to be found, crushed under the rubble. On top of that, the landmarks of a brand-new settler colonial city rise high. Although Street View creates the illusion of looking through someone’s eyes, the first-person point-of-view doesn’t belong to anyone in particular but to many. A spectral entity, the bearer of Palestinian memory is an impersonal, collective revenant. And these memories are (paradoxically) full of absences, flaws, and wounds, like the distorted and imperfect images they are channeled through.

Mahdi Fleifel’s second film in the programme, 20 Handshakes for Peace, materialises that fragmented memory within the fabric of the image. Fleifel utilises footage of Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin and Bill Clinton during the signing of the Oslo Accords, a series of interim agreements that were supposed to bring peace to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but ended up worsening the situation. Accompanied by a recording of Edward Said’s audio commentary, the film reiterates the handshake between Arafat and Rabin twenty times, slower and slower. The traumatising impact of this historical moment is rendered through the act of forced repetition—not so different from a revenant in its own right, the haunting gesture keeps coming back, like a broken record. Said’s analysis of the unequal outcomes as well as the contrasting attitudes of Israeli and Palestinian officials, is underlined by Fleifel’s specific focus on the mechanics of the handshake. Arafat is the first to extend his hand. The slowed-down motion and gradual close-up zooming in on the handshake make the resentment and disappointment felt by the Palestinian people weigh more and more as if the images themselves exclaim, “How could they?”

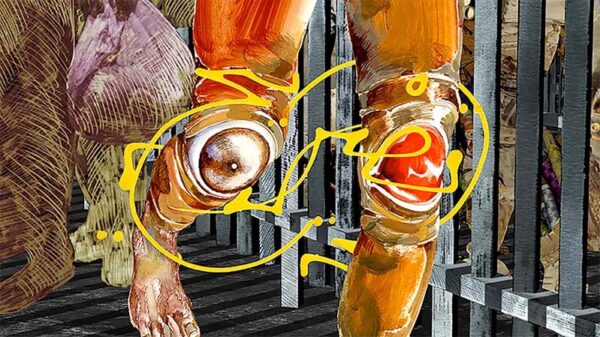

What Said qualifies as the “fundamental irreconcilable” between Israelis and Palestinians, namely the issue of land-claim, also stands out as a subject matter throughout the programme. According to Palestinians, the issue should be considered on three levels: through the land that belongs to them but has been taken away; the land they are imprisoned within; and for those in exile, the land to which they cannot return. Samira Badran’s Memory of the Land and Annemarie Jacir’s Like Twenty Impossibles address this through the checkpoint apparatus, a space of Israeli necropolitics par excellence. Badran’s approach is striking in the sense that she represents the extreme control, surveillance, and incarceration that Palestinians are subjected to as an embodied, physical experience. She visualises those sufferings through a dismembered animated figure. The depiction of a body with severed legs attempting to escape from the checkpoint renders the state of brokenness—and the broken state—shockingly visceral. While the image of one leg longing to leave and the other wanting to stay reflects the clashing sentiments towards the land, we’re urged to see it as more than a mere metonymic device. It is a reality for Palestinian people, and Badran manages to avoid any sort of generalisation that would make us forget that.

Memory of the Land (Samira Badran, 2017)

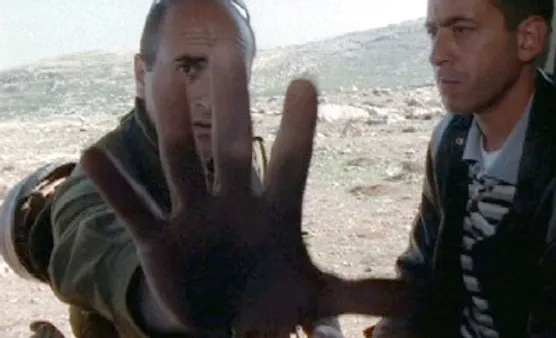

Where Memory of the Land illustrates Palestinians’ collective experience of confinement through dark and suffocating spaces, Jacir sets Like Twenty Impossibles in the vast, barren landscapes of occupied Palestine. The film sees a Palestinian film crew who, on their way to Jerusalem, decide to detour and avoid checkpoints. Subsequently, their unfortunate encounter with Israeli soldiers becomes emblematic of how arbitrary and cruel the Israeli politics of space are. Along the journey and during the passport-control scenes, the camera’s wandering gaze emphasises the wide expanse of the surrounding land. Images of roads stretching all the way to the horizon are usually associated with a sense of freedom and power over space, yet Jacir reminds us that this is exactly what Palestinians are deprived of; military violence has a drastic impact on people’s daily existence.

Similarly, the increasingly tense interactions between the film crew and the border patrol epitomise the arbitrary hierarchies that the Israeli state imposes to rob Palestinians of their fundamental human rights. Jacir paints each member of the crew as having a different administrative and social status according to IDF soldiers—the soundman, an Israeli citizen, and the actor, a Palestinian from Ramallah. The filmmaker-character with American citizenship, a fictionalised version of Jacir herself, holds a legally privileged position in comparison with her compatriots. No matter how much she claims to be Palestinian.

While relevant to the Palestinian people’s overall social, economic, and administrative conditions, the diversity of these experiences is reflected in the practices of their artists, who share common aspirations and goals, as evidenced by the films selected for the Glasgow Short Film Festival. Some put their work on the line, while others risk their lives—whether in Gaza, the West Bank, Israel, or abroad—channeling grief, anger, determination, and hope through their images. Despite facing sanctions and losses, they heed their small but resolute inner voice, much like the director in Jacir’s film who whispers to her cameraman, urging them to “keep filming”.

Mentioned Films

I Signed the Petition

by Mahdi Fleifel, Germany, Switzerland, United Kingdom, 2018, 11’

Immediately after a Palestinian man signs an online petition, he is thrown into a panic-inducing spiral of self-doubt. Over the course of a conversation with an understanding friend, he analyses, deconstructs, and interprets the meaning of his choice to publicly support the cultural boycott of Israel.

In the Future They Ate From the Finest Porcelain

by Larissa Sansour and Søren Lind, United Kingdom, Denmark, Qatar, 2015, 29’

A narrative resistance group makes underground deposits of elaborate porcelain—suggested to belong to an entirely fictional civilisation. Their aim is to influence history and support future claims to their vanishing lands.

Your Father Was Born 100 Years Old, And So Was The Nakba

by Razan AlSalah, Palestine, Lebanon, 2017, 7’

For someone who is not a digital native, the wonders of Google Street View can be overwhelming and discombobulating. When Oum Amin, an elderly Palestinian woman, is taken through the streets of her hometown of Haifa, she is immersed in vivid memories from her past.

20 Handshakes for Peace

by Mahdi Fleifel, Palestine, Germany, 2014, 5’

September 13, 1993: Two national leaders reach out and shake hands, while a third one watches. Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin, and Bill Clinton in the garden of the White House. A historic moment, repeated 20 times, tainted by countless shattered hopes. On the soundtrack Edward Said expresses his outrage at the Oslo Peace Accord which was settled by this handshake.

Memory of the Land

by Samira Badran, Spain, 2017, 12’

Palestine. A body is trapped at a checkpoint; an essential mechanism of the Israeli occupation. The body is pierced by structural and physical violence, which is aggressive and arbitrary and prevents and attacks its free movement and existence.

Like Twenty Impossibles

by Annemarie Jacir, Palestine, 2003, 17’

When a Palestinian film crew averts a closed checkpoint by taking a remote side road, the political landscape unravels, and the passengers are slowly taken apart by the mundane brutality of military occupation. Both a visual poem and a narrative, like Like Twenty Impossibles, wryly questions artistic responsibility and the politics of filmmaking.