Live It or Leave It

Living Reality

An exploration of the emotional divide between fiction and reality in the American sitcom, Philip Thomson’s Living Reality questions how we consume images at large.

I have never been a fan of Friends. I always found it difficult to relate to (or, to be honest, to tolerate) the show’s characters, much less laugh at their jokes. Growing up in an era in which the televised sitcom was gradually overtaken by made-for-streaming comedy series, the pre-recorded laughing track struck me as an outdated device that kept me at arm’s length. I became wary of the sitcom as a genre, skeptical of its attempts to take away my freedom to laugh at what I actually found funny. And yet, the very aspects I used to struggle with can sometimes be turned against themselves and push the genre towards new intriguing paths. So it is with Philip Thomson’s 2024 short, Living Reality.

Formally speaking, Living Reality unfurls and feels like a sitcom: from the grainy digital look harking back to a late 90s/early 00s aesthetic to all the different tropes of the genre: funny catchphrases, over-the-top performances, theme songs, and, of course, the laughing track (also known as canned laughter). The short’s setting might be the most familiar element of all: a huge living room, shot from one to three different perspectives at most, and inhabited by four friends/roommates chatting about their dating life and their daily struggles. Everyone always knows the right thing to say, an effortlessly witty repartee that never loses its comedic timing—everyone except Theo, the short’s main character, but arguably the sitcom’s most sidelined one. His presence feels off, and not in a scripted way. Of all the people dotting Living Reality, he might be too “real” for the TV show Thomson stages: he stammers, coughs, and sneezes, while the others stare at him in uncomfortable silence.

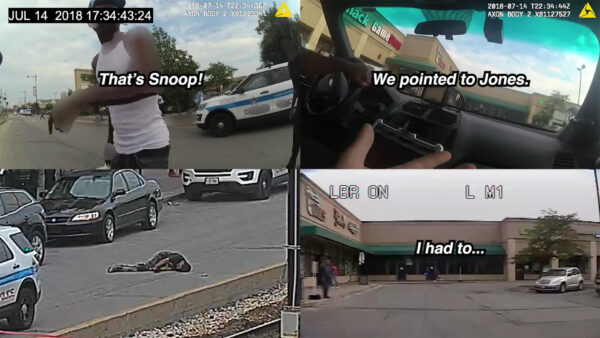

When Theo gets enough of them, he returns to his flat. Much emptier and messier than his friends’, the place is captured with the same overly artificial sitcom look: a flat and frontal point of view. To unwind, he turns on the TV; from that moment, both he and the viewer are presented with a very different set of images made out of scenes from everyday life, in which people seem unaware of the presence of a camera. Their conversations flow naturally, addressing random or sometimes very private topics (such as erectile dysfunction). The scenes are stitched together without an apparent order or overarching narrative: there is no build-up, no climactic payoff, and no clear time frame.

The film’s switch between Living Reality’s sitcom and the “actual” reality Theo watches on TV doesn’t just question the alleged dichotomy between fact and fiction, but also our broader attitudes towards the images we consume. The laughing track—or, rather, its absence after anything Theo says—is a starting point to warn the viewer against the medium.

In his 2003 essay “Will You Laugh For Me, Please”, Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek tries to interpret the phenomenon of canned laughter and its implications. According to Žižek, canned laughter represents a physical manifestation of the “return of the repressed”, through which our innermost emotions can be completely externalised. Although perceived as weird and “primitive” at first, the idea of “laughing and crying through another” has quickly become normalised in our culture. Challenging theorist Robert Pfaller’s concept of interpassivity—which states that in today’s mediatic landscape one cannot consume anything passively but must instead interact with everything they watch and experience—Žižek asserts that the issue with canned laughter is that it deprives us of our passivity: we are prevented from enjoying our own “passive satisfaction” since a machine is doing it for us.

Žižek’s theory of passive spectatorship could be one way of explaining my skepticism towards sitcoms at large. I am not the only one stripped of their right to passivity, though. Theo himself, both as a spectator and performer, is struggling to reclaim the same in a context in which everything demands to be performed for the viewer. And what could be more performative than the kind of approval one receives through laughter and applause? Theo is trapped in a box: the only way out is to give in, say the catchphrase, and let the laughs take over.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #5—a tandem workshop set during Lago Film Fest and FeKK Ljubljana International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Leonardo Goi.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!