Machinic Visions

Their Eyes

In Their Eyes, screen recordings testify to the experience of online micro-workers from the ‘Global South’: their job is to train AI for self-driving cars to navigate the streets of the ‘Global North’—a labour process that, by design, steers towards a real abstraction, and a looping nightmare.

In his analysis of the division of labour in the manufacturing workshop, Marx describes how the worker becomes a “fragment of his own body”. With the transformation of the workshop into the machinic factory, this process intensifies. The machine becomes a “dead mechanism” which rules over workers just as they “are incorporated into it as living appendages”. As workers become a “mere accessory” of the machine and, by extension, capital, which serves as the real unity and consciousness of the concrete labour process, this process “suppresses the many-sided play of a person’s muscles and makes all free activity—physical and mental— impossible”. Ultimately, this destructive fragmentation is only a moment that moves beyond itself, towards a real abstraction: the production of surplus value and the latter’s realisation in terms of profits, all put back towards never-ceasing accumulation, a looping nightmare that continually reproduces the fragmented, dislocated worker and their unhappy partner, capital.

What happens, in our deindustrialised world, when this logic of fragmentation and division encounters the arena of digital work? What if the machine is no longer immediately present as spluttering, smoking mass on the shopfloor but instead takes the opaque sheen of a future technology in a faraway land? Nicolas Gourault’s Their Eyes (2025) allows us to glimpse the digital intensification of machinic fragmentation. Gourault’s film investigates the labour of ‘click workers’ from the ‘Global South’ who label and categorise images of traffic in order to teach the AI of self-driving vehicles to read and navigate the world. By situating the viewer in the digital, labouring space of these workers, the film traces how such work reduces them to machinic (eye) organ and mere appendage to the cars. However, in contrasting recordings of workers’ categorising street images with workers’ self-shot imagery of their homes, the film longs for a way out of this fragmentation, to wrestle a moment of negation from this all-consuming vision and see the world afresh.

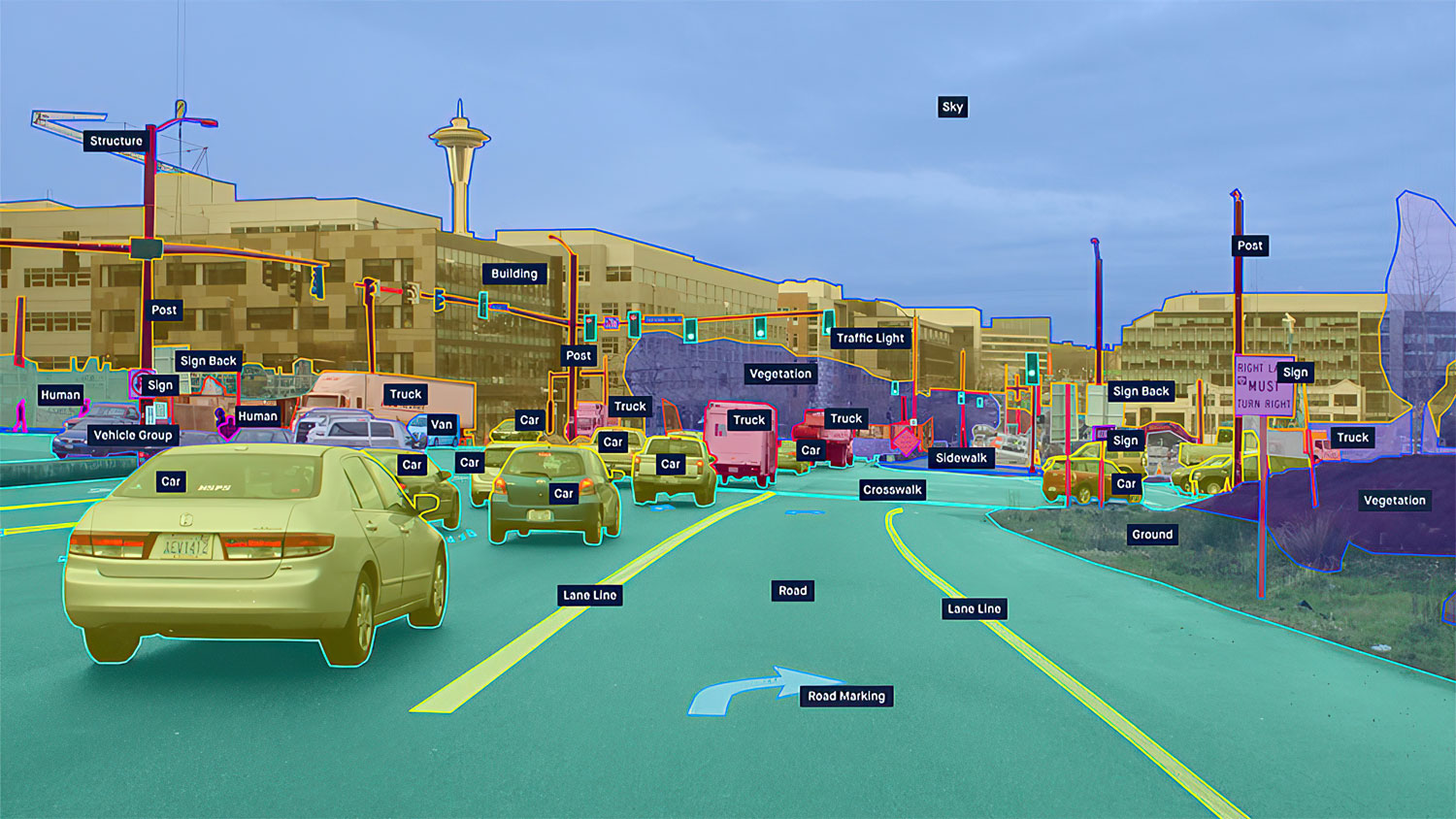

The film is composed in two sections (with anonymous workers’ voice-overs continuous throughout). The first section is made up of a slow montage of screen recordings taken from workers’ laptops. Over Google-Earth-like still-images of roads, workers “segment” objects, people and buildings and attach anonymous labels to them (‘vehicle’, ‘person’, ‘shrubbery’). Such workers must trace the shape of each roadside feature with their cursors, creating a cut out of the object which they then mark over with translucent colours, as if carefully using scissors and a highlighting pen to divide and blot the image. We initially see close-ups of the workers tracing the minutiae of this segmentation before moving to still-images of completely segmented streets. In these finished images, highlighted segments consume the image with purples, blues and yellows so that “no space is left unlabelled”, as one worker puts it. As the section develops, fully labelled images give way to an abstract collage of overlapping highlighted objects, arrows, markings and labelling. Disconnected digital cut-outs of highlighted people, bikes, trees and traffic cones begin to consume the frame. Finally, we cut to the moving view of the car as it drives through the street and ‘reads’ the, now squirming, highlighted segments of its objects and surrounding, as if autonomously.

Beginning as it does with the laborious task of annotation, our initial section might at first appear to insist upon the, by now, well-stated invisibility of (digital) labour: “it’s as if we don’t exist”, a worker insists. The floating automaton of AI and its seemingly autonomous vision enables us to forget that it is truly artificial, that it relies upon enormous swathes of exploited labour, a global infrastructure, whether in data centres, cobalt mines or the aged laptops of the digital underclass. The first section, in foregrounding workers’ voices and their workstations prior to images of the car’s ‘autonomous’ vision, makes such work visible as work. At its most didactic, the sequence also reminds us of the global unequal wage distribution, as workers recount their use of VPNs to get higher wages, or the ever-present threat of their eventual replacement by a self-mapping AI.

One worker likens his task to “painting”. This carries both a false ring and an aesthetic longing as the mechanical cursor movements and their attended highlighted blobs absorb the screen. How close to free expression of painting can the repetition of cutting, splicing and categorising images of the world on behalf of an AI really be? Instead of an aesthetic practice, the section presents the totalised vision of a world divided and divisible, containable and amendable to the self-driving machine. In the repetitive force of the sequence’s machinic vision, whether in showing us isolated segmented objects or collaged highlighting, we begin to see as “living appendage”, as a fragmented body, severed by the valorisation process from its boundless physical and creative faculties.

What we see then is not simply that labour is performed and hidden. Rather, in positioning us inside a dissociated, machinic vision, any lingering sense of this labour’s concrete usefulness recedes in the shadow of its increasingly abstracted functionality. At the section’s end, we cut to a birds-eye-view of a gridded, digital map. This shot zooms out from the now familiar segmented, highlighted shapes into an ever-widening, already-mapped digital space: from workers’ minute tasks to an uncapturable, global infrastructure of AI mapping that escapes its discardable labour inputs. This scalar movement grasps after a moment of greater abstraction. Amongst the pixelating expansion, we are made to ask: what is all this for? It is in offering us this discombobulating vision mediated by capital that Gourault’s film locates the abstraction of an abstraction of an abstraction; real space becomes blotted image, workers become fragmented appendages incorporated into capital and the particular becomes increasingly conditional to same greater mass, all so that value might be realised.

Their Eyes (Nicolas Gourault, 2025)

However, in the film’s second section, we are freed from this alienating vision. This section consists of self-shot, shaky footage of streets in workers’ home countries. In one extended, high-angle image, a worker shoots a street in Nairobi from his phone camera. The return of sound and unhighlighted vision, with people and objects no longer obscured by segmentation, offers a noisy excess compared with perfectly categorised vision of the self-driving car. The “chaotic” Nairobi street would “take a lot of time to annotate”, a worker explains.

Contra fragmentation, the workers’ control of the camera and the returned sensual domain of colour and sound offers their “many-sided play” of “free activity” back to us. In one shot, a worker moves her camera around her small garden finding cacti, cats and grass as she does so. Against the prior section’s cold digital space, there is a sensory force to this shot, both in its material and embodied, shaky shooting quality. The worker pretends to annotate and segment this real space, as if she were at work, but this attempt rings false. In partially returning this preponderant world back to us, there is an excess of non-identity with the preceding, alienating imagery of segmentation and categorisation, or the machinic vision of capital.

There is an extended tracking shot in Jean-Luc Godard’s British Sounds (1969) through a car factory in which, atop its screeching sounds and moving bodies, a voice-over speaks of capital’s domination over workers—their ultimate reduction to “congealed quantities” of abstract labour as Marx puts it elsewhere. The factory and workers escape the operative falseness of the voice-over’s analysis, their particularity impossible to capture in the abstractions of capitalism, and yet are ultimately reduced as such by them. The worker’s garden functions much the same here. In falsely repeating the task of segmentation, she reveals how much her own vision both escapes and is reduced by her everyday reduction to mere labour input.

What remains from this excess is the potential of a world no longer disfigured by the capital relation. Such a potential is repeatedly figured here in the aforementioned aesthetic longing. This desire is captured in workers’ self-directed imagery and the analogy of their labour to a more creative practice clearly lacking in the segmentation task itself. “I like to draw”, as someone puts it. It is a longing to be reunited with those creative and physical faculties absolutely delimited by their compulsion to work. The partial performance of those faculties here throws the poverty of labouring as capital’s organs, its digital infrastructure and the AI vision it entails into sharp relief. Indeed, Marx’s critique of the capitalist labour process also contained an aesthetic dimension. Freedom from abstract labour and its fragmentations might mean instead the possibility of a “free play of his physical and mental powers”.

At the end of her garden shot, the worker walks away from the garden towards the dying light of a sunset. “I don’t know if you can see the sky, how it looks, with its different tones”, she says. Such tones, and their useless beauty, sharply differentiate from the functional colours that segment the self-driving vehicle’s visions. This attention to the aesthetic wanes after what Theodor Adorno called the potential for works of art that are “plenipotentiaries of things that are no longer distorted by exchange, profit, and the false needs of a degraded humanity”. Their Eyes hinges on this opposition between value’s abstracted vision and the latent possibility of an exuberant world without its distorting mediations. Each falsifies its other. With our worker’s tonal sunset, we glimpse the falseness of the world captured by capital and the possibility of non-identity with it. With our machinic visions, we glimpse how far we are from this possibility and how much is left to be done.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #8—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Michaël Van Remoortere.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!