Media Revisited

The Politics and Poetics of Desktop Documentaries

Championing the legacy of filmmakers like Harun Farocki and Chris Marker, contemporary filmmakers reclaim the computer screen as a site of reflection and resistance in a time when algorithmic culture and censorship define our mediatised society.

Some films ask us not just to look, but to look again. Made entirely from screen recordings, desktop documentaries revisit media as both method and meaning. It is ultimately a gesture of return shaped by navigating the screen. Such films are not interested in merely showing media, but in re-seeing and reinterpreting it, through a process filtered by the computer interface.

In the programme “Screening the Screen: Desktop Documentary”, curated by Aylin Kuryel for Go Short – International Short Film Festival in Nijmegen, the films selected repurpose other work, turning research into narrative, browsing into rhythm, and the act of watching into an excavation—a digital media archeology if you will. I first encountered Kuryel in her capacity as a filmmaker through her documentary Translating Ulysses (2023), a portrait of a Kurdish translator’s endeavours to bring James Joyce’s labyrinthine text to their native language, co-directed with Fırat Yücel, whose most recent short, Doubts (2020), is part of Kuryel’s Go Short programme. Like in her film, Kuryel pays close attention to the politics of translation, be it linguistic or visual, revealing how acts of interpretation and mediation shape what we come to know and feel.

The desktop documentary transforms the computer screen into both a workspace and a stage. The screen is no longer a flat surface but a layered terrain, where the archival dust is removed by RGB luminescence that revives the past through new means of interaction. Emerging from the traditions of screencasting and essay film, it blends creation and reflection in real time, revealing a mind at work through the rhythm of clicking, scrolling, browsing, typing, highlighting, downloading, zooming in, replaying, and so on. These films invite one to pause, look again, and reconsider. In doing so, they dissolve the line between analysis and storytelling, turning the desktop into a shared site for observation and narrative where showing something becomes indistinguishable from thinking through it. Revisiting media here means re-seeing not for clarity but for complexity.

The programme opens with Kevin B. Lee’s Transformers: The Premake (2014), a landmark desktop documentary that defined the form as we know it today. Through the screen-recorded navigation of his own computer desktop, Lee turns 355 user-uploaded YouTube videos of the making of the blockbuster Transformers: Age of Extinction into a layered investigation of global filmmaking, digital spectatorship, and media economics. Clicking, dragging, resizing, and sequencing all become a digital choreography that unveils how Hollywood operates not just as a cultural engine, but as a parasitic presence feeding off unpaid fan labour and viral promotion. This database of existing media content forms the foundation of the film’s interrogative nature. It’s easy to spot on the screen the external hard drive that stores them all, poignantly named after Harun Farocki, the master film essayist to whom The Premake clearly pays tribute, placing Lee within a lineage of critical media practitioners who turn the archive into an engine of and for reflection.

Transformers: The Premake (Kevin B. Lee, 2014)

What makes The Premake compelling is how it repurposes fragments of spectacle to reveal the machinery behind said spectacle. From production shoots in Detroit to viral YouTube uploads later taken down by Paramount, Lee maps the cinematic industrial complex, exposing the blurred boundaries between promotion, surveillance, and participation. The desktop becomes a site of inquiry where media is not consumed but dissected, a space for critical proximity. Lee’s work establishes the principles of the desktop documentary: the screen as canvas, interface as narrative, and media as both material and critique. There is nothing nostalgic about revisiting media here. It is rather a way of peeling back layers of cultural production to expose its economic and ideological undercurrents. The Premake invites us to rethink what we can do with media objects and what they can do to us.

Like The Premake, Tang Han’s Pink Mao (2020) belongs to a lineage of essayistic cinema that questions how we see. Pink Mao launches with a radical proposition: the Chinese 100-Yuan banknote, declared red by the Chinese central bank, is, in reality, pink. Tang shares with Farocki a forensic sensibility, a commitment to analysing the political life of images. Yet, where Farocki’s focus often fell on systems of surveillance and control, Tang dwells in the nuances of perception and symbolic drift. Her desktop is a site of inquiry for her gentle provocation that arranges visual evidence not to argue, but to wonder. The casual observation on colour perception unfurls into a critique of collective memory and state symbolism, where femininity, monetary value, and political iconography collide. The .jpg image of the 100-Yuan banknote takes the form of a media object ripe for digital image analysis. The extracted information reveals more than its exact colour hue—it points to the cultural assumptions, like ideas of national identity, gender, and political authority, that saturate its meaning.

Pink Mao operates on two desktop levels. While the computer screen mediates much of the film’s archival inquiry, the original “desktop”, the physical surface of the working table, emerges as a crucial visual stage. It is on this surface that the banknotes are placed, examined, and framed with care. Tang’s hands enter the shot delicately, nails painted a matching shade of pink, blurring the boundary between analysis and embodiment. Her holding, turning, and lighting the banknotes become tactile acts of inspecting that make what might otherwise remain a disembodied critique, intimate. This second desktop offers a physical counterpoint to the screen, rooting abstract discourse in the materiality of colour, currency, and the feminine body. As a result, Pink Mao reveals how even the most symbolic forms of power, such as money, masculinity, and Mao, can be touched, folded, and re-seen.

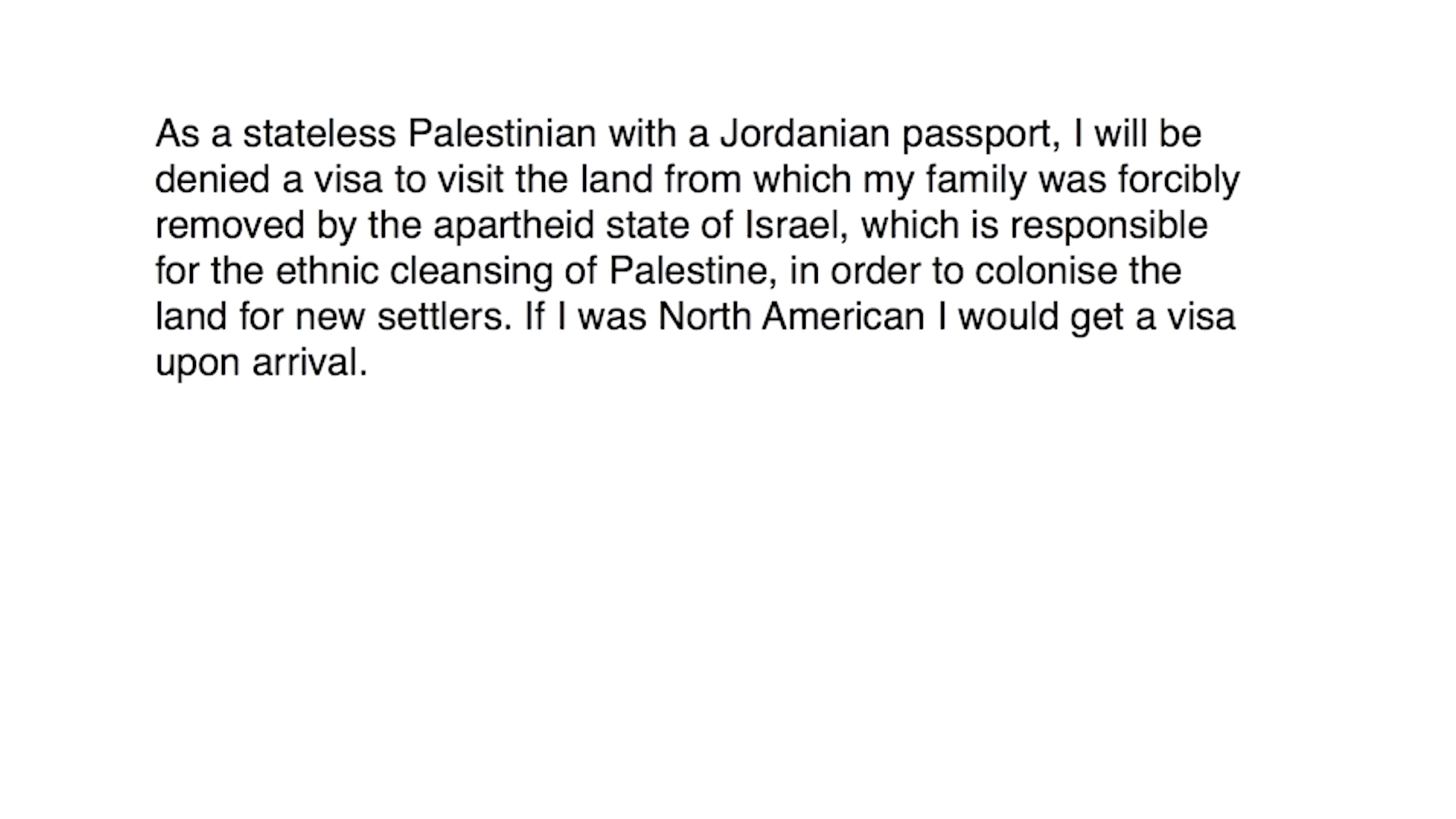

If Pink Mao grounds critique in touch and tactility, Muhammad Nour Elkhairy’s I Would Like To Visit (2025) turns to the desktop as a space for voicing the desire for liberation through language. Typing and retyping a deceptively simple wish to travel, the film unspools entirely through the visible act of text composition on a word processor. What begins as a sentence soon folds into itself, revised, reworded, and burdened with the weight of history, identity, and exclusion. Elkhairy’s Palestinian-Jordanian identity anchors the piece in lived experience as the film silently documents the impossibility of mobility for a people rendered stateless by the colonial regime of Israel. Each textual edit seems to evoke the presence of a wall, of settler colonialism, of dispossession, of ethnic erasure. The sonic backdrop of white noise and ambient anxiety underscores the tension of being continually denied existence. In that mirroring of words and silence, visibility and erasure, I Would Like To Visit becomes political witnessing in which the desktop is transformed into something between a courtroom and a confessional, where language is endlessly negotiated.

I Would Like to Visit (Muhammad Nour Elkhairy, 2017)

I Would Like to Visit echoes the tradition of avant-garde structuralist cinema that sought to strip language down to its elemental, visual, and rhythmic core. Like Michael Snow’s So Is This (1982), which turns individual words into singular frames of film, Elkhairy’s desktop essay makes each sentence a site of tension and an object to be read and experienced in time. In Hollis Frampton’s Zorns Lemma (1970), the substitution of letters for images reflects a movement from symbolic meaning to sensory engagement; similarly, Elkhairy replaces uninterrupted narration with revision, hesitation, erasure, and rewriting—a rhythm imposed by colonial power that limits self-expression and, by extension, freedom. And like Su Friedrich’s Sink or Swim (1990), which uses text as a tool to address personal history and patriarchal language, I Would Like to Visit becomes an unsent letter to power, both personal and political. Typing and deleting mirror a psychological negotiation as much as a narrative one. In each case, language is not a given but a structure to be wrestled with, to be dismantled and reassembled as a way of confronting one’s position in the world.

Charlie Shackleton’s Lasting Marks (2023) turns the desktop into a radical judicial site, reassembling archival evidence into a layered, reflexive mode of storytelling that critiques institutional power. Revisiting the 1980s Operation Spanner trial, a case marked by institutional homophobia and the criminalisation of consensual gay sex, the film draws on documents once used to police pleasure. Court reports, police records, media clippings, and floorplans of prisons appear on screen in their full bureaucratic absurdity, while Roland Jaggard’s voice-over testimony offers a human counterpoint. Jaggard is one of the sixteen men prosecuted in the Spanner case. As a desktop documentary, Lasting Marks places the archive in dialogue with affect, asking us to read and listen at once. The screen becomes a space to reencounter these documents as media artifacts carrying emotional weight, prejudice, and power. The film’s subjectivity forms not through personal memory, but through mediated engagement with the traces of others’ lives. Revisiting media here means reclaiming such a subjectivity.

In an essayistic fashion, the film places critical attention on the ways media mediates meaning. Shackleton’s refusal to excerpt “key” lines from the documents, instead allowing full texts to linger on screen, functions as a powerful counter to conventional documentary practices. Viewers are invited to scan the images, search, and reread, to enact their own meaning-making against the grain of the official narrative of police, state, and traditional media. As an act of media archaeology, Lasting Marks unearths not just what was said or done, but how power was maintained and manifested through language, form, and silence. Shackleton does this with the minimal imagery of just paperwork and a single voice accompanied by clicks of a mechanical slide projector, emphasising the violence of erasure these men endured, and the ongoing labour of giving that history back its texture. The desktop, in this case, becomes both an archive and a legal battleground.

Lasting Marks (Charlie Shackleton, 2018)

In Yücel’s Doubts, on the other hand, the screen becomes a palimpsest of digital labour: scrolling spreadsheets, categorising protest clips, hovering over frames as political stakes are debated, blurring faces. The film emerges as a piercing self-reflexive desktop documentary that lays bare the haunted terrain of post-production under censorship. Positioned as a ‘desktop thriller’ by the author, the film dramatises an imaginary text exchange between two filmmakers revisiting the 2013 Gezi Park Resistance through the mediated distance that time brings when revisiting archived footage. The tension does not lie in the footage itself, but in the pause before inclusion: What can be shown? What can be said? What is too dangerous to document, let alone screen? This is cinema composed not of action, but of the hesitation that comes after action that seeks to hold power responsible for injustice. Through its fragmented, fictional conversation, Doubts exposes the dread that pervades creative processes in politically repressive contexts, where self-censorship becomes indistinguishable from survival.

Within the desktop documentary form, Doubts performs an act of resistance by foregrounding the doubt itself in the refusal to finalise, the deferral of voice. Its interface, filled with banal admin tasks, chats, and metadata, transforms into a psychological landscape of suppression and fear. Yücel echoes his previous works, some in collaboration with Kuryel, this programme’s curator, in speaking up against censorship and authoritarian control. Doubts is an extension of his long-standing engagement with political filmmaking and activism in Turkey, where, through platforms like Altyazı Fasikül: Free Cinema, he has supported filmmakers at risk and foregrounded resistance through collective, essayistic forms. The film reclaims media not by completing it, but by circling around its silences and its buried potentialities. The very impossibility of representation becomes the subject, and the screen, usually a tool of expression, now discloses creative paralysis. Doubts does not just revisit the Gezi archive; it becomes a living document of creative and political suppression, where editorial work is both a risk and a radical gesture.

These works capture a moment in the evolution of the film essay, championing the legacy of filmmakers like Farocki and Chris Marker, while opening new avenues through novel cinematic devices that are more accessible. In a time when surveillance, censorship, and algorithmic culture define the visual world, these filmmakers reclaim the screen as a site of reflection and resistance, demystifying the politics of the screen.