Memory in Textures

Recalling Experiences Through Surfaces and Matter

Certain films call to action our entire sensory sytem: the moving image is not only seen but heard and felt too. In shorts by Neritan Zinxhiria, Slava Doytcheva, Norika Sefa and Ana Hušman, layered textures of memory are tactically explored.

Images alone can no longer be the subjects of memory. That is too big a responsibility. Several experimental Balkan entries at this edition of the FeKK Short Film Festival in Ljubljana understand this and exceed the optics, offering instead acts of remembrance as sensory experiences.

In today’s image-saturated visual culture, we’ve moved beyond the idea that the cinematic experience depends mainly on sight. The moving image is not only seen, but it is heard and felt too, combining multiple sense organs that become means of perception orienting both body and mind in the formation of the filmic reality. Certain films, especially those that neglect established formulas of narration, call to action our entire sensory system, which can surprise us by its inherent ability to detect different intensities and textures of cinematic signification. From how we feel and perceive a movie to how it touches our unconscious mind, film and spectator are like parasite and host, film scholar Thomas Elsaesser tells us in his introduction to film theory through the senses, taking turns occupying each other to let the cinematic reality unfold.

What about the cinema of memories? What layers of reminiscence does a film have to offer? A cinema of the senses does not understand memories as inner-psychic phenomena alone. Instead, it considers them processes that awaken our perceptual apparatus in its entirety, much like how we perceive and register the outside world through our body as a whole. Memory events can be relived through cinema as mediated experiences that connect us with our internal past.

Similarly, a number of experimental documentaries from the 2024 FeKK BAL: International Competition programme invite us to engage senses beyond sight and to immerse ourselves deeper into someone else’s past that feels almost as tangible as the original memories themselves. These films use a variety of media to evoke a rich sensory experience that both transcends traditional narrative and expands on the personal documentary genre. The textured nuances of analogue media, full of imperfections and organic qualities, draw attention to the surfaces of their images, creating a visceral connection to the memories they embody.

This is most evident in Neritan Zinxhiria’s Light of Light, an experimental piece that seeks to uncover new dimensions of memory through its textures. The film is centered around glass plate photographs created by a monk in the early 20th century using his handmade camera to capture the remote monastic state of Mount Athos, a place largely untouched since Byzantine times. Ninety years later, the filmmaker reconstructs and reinterprets these images, intertwining them with his surviving Super 8 footage captured over the years. The result is a mystic, meditative work where time appears frozen and unfrozen at will, evoking a haunting sense of a world long past—deep time, if you will. The grainy, black-and-white contemporary images of monks moving about their daily routines feel as if they come from another realm. The filmmaker’s attempt to “meet” the monk through film, as suggested by the opening text, creates a ghostly dialogue across time that goes beyond mere historical documentation—an embodied experience that evokes the spiritual and the ephemeral.

Light of Light opens with a striking scene in which a monk, shrouded in soft focus, approaches the camera set at a low angle, forming an aura made of film grain and raindrops—an elemental chemistry—that coalesce into a larger, almost iconographic form. As he draws nearer, he quietly whispers a prayer and, in reverence, kisses the camera, treating it as if it were a religious object—perhaps akin to a Bible or an icon, much like the glass plates that echo Byzantine iconography. The contact of his palm and lips against the lens leaves ephemeral imprints that slowly fade away, evaporating into the air—continuing on the elemental breath of the scene—a poetic metaphor for the transient nature of both memory and the moments captured on film.

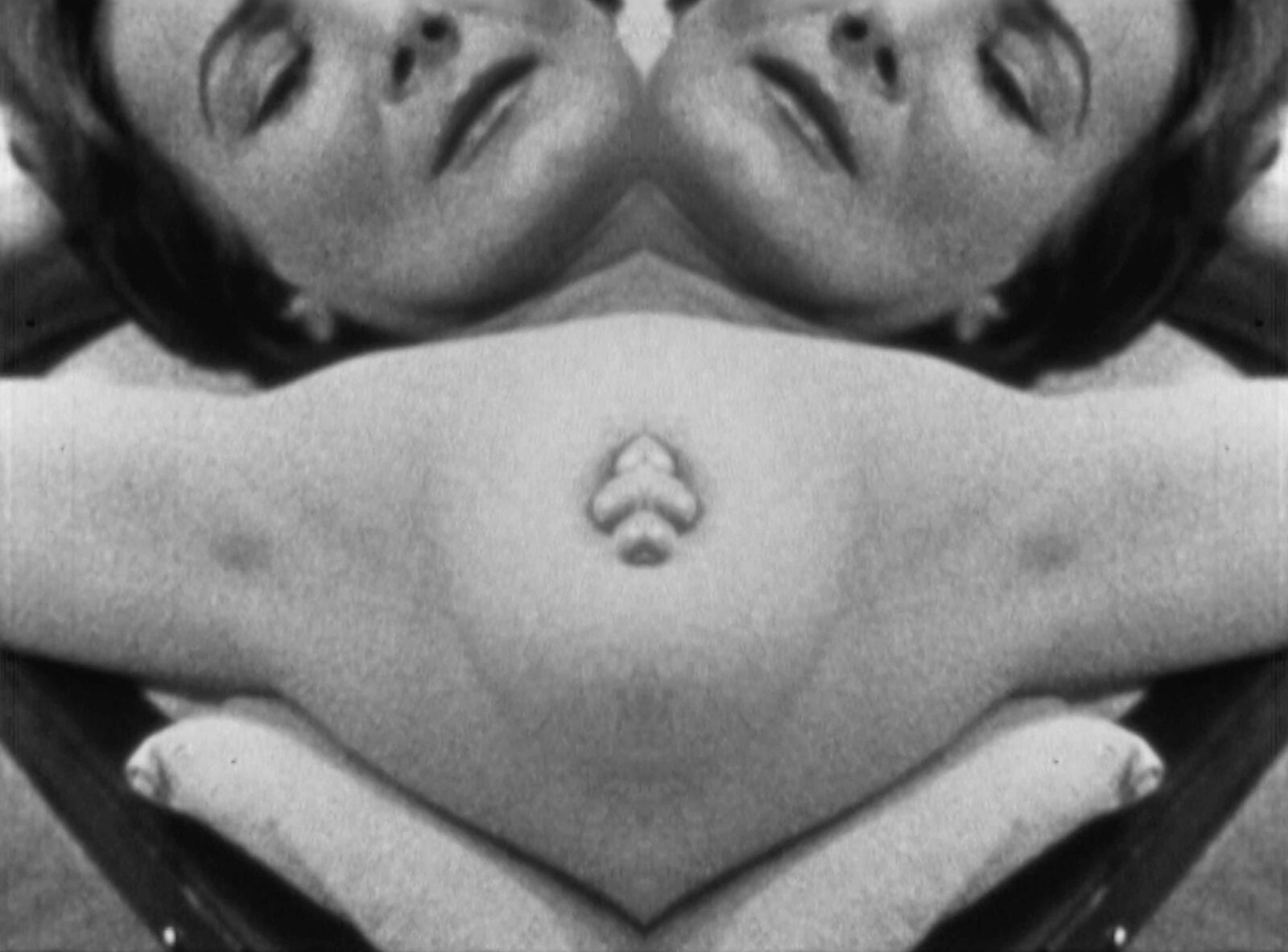

© Like A Sick Yellow (Norika Sefa, 2024)

Our gaze turns to surfaces and matter, becoming what film theorist Laura Marks calls “haptic perception”—the eye functioning as the touch organ eliciting a sensuous response coming to contact with a sensuous (filmic) object. The opening serves not only as a beautiful blessing but also evokes perhaps the most famous opening in cinema history: Ingmar Bergman’s Persona (1966), in which a child reaches out to touch the screen, creating a visceral connection between the eye and the hand. Similarly, in Light of Light, the monk’s gesture reinforces the idea that the act of seeing and touching are intricately linked.

The glass on a camera’s lens is not so different from the glass-plate-photographs that carry the physical scars of time—cracks, fading, and chemical deterioration—turning images into tangible relics and haptic memories. Zinxhiria curates the plates with great care, often in pairs, mimicking the arrangement of Byzantine icons and forming an architectural structure that mirrors the spiritual spaces of Greek Orthodox churches, imbuing the film with sacredness and deep resonance. The filmmaker’s physical and emotional encounter with the monk’s memories through his photographs incarnates the act of remembrance through media materiality.

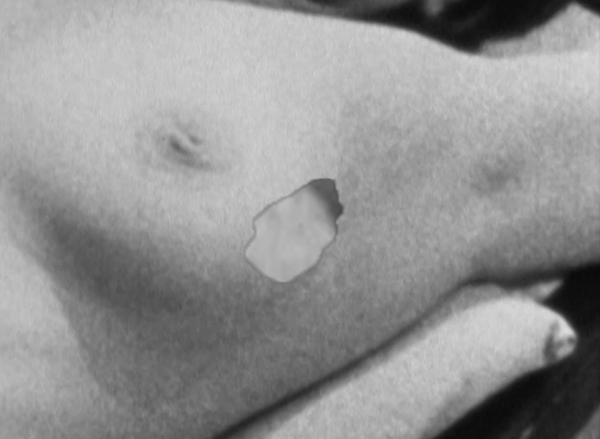

Slava Doytcheva’s Quadrant presents a poetic yet clinical examination of touch, memory, and imagery, employing the textures of film and tactile encounters to explore the deeply personal experience of living with a recent cancer diagnosis. Divided into four segments, the film dissects a found educational footage reel from 1971 featuring a Swiss Italian TV programme on breast cancer prevention. This archival footage of a doctor examining a woman’s breast for signs of cancer becomes a foundational image that Doytcheva re-engages with, layering it with her own experience. The film progresses as a meditation on touch—both physical and metaphorical—as the filmmaker comes to terms with her diagnosis and attempts to process the profound changes to her body and identity.

In the second segment, “Discharge Summary”, she mirrors the image, reflecting the clinical doubling of cells while reading her diagnosis in a raw, unfiltered voiceover. The third section slows the footage down to a frame-by-frame examination, accompanied by a reading from Getting Well Again, a book that calls for a meditative confrontation with illness. This repetitive looping mimics the persistence of memory and illness, which can never fully be escaped, even when healed, as if asking how we can heal from memories.

The final quadrant introduces a crack in the image, symbolising the filmmaker’s fractured sense of self, as the cancer diagnosis strips away layers of identity that her emotional voiceover enumerates: “feminist, activist, daughter, sister, lover, cutie… take it all off,” the disease seems to order. We’re faced with a film and a filmmaker equally exposed and vulnerable while the images on screen, despite their repeated usage, continue to evolve with each viewing. Through these textures found both in image and voice, Doytcheva perhaps suggests that the process of confronting cancer, like the process of filmmaking itself, involves a reordering of time and space, a reimagining of the body’s relationship to illness, and an embrace of corporeal memory.

© Light of Light (Neritan Zinxhiria, 2023)

Much like Doytcheva’s Quadrant, Norika Sefa’s Like a Sick Yellow uses repetition, fragmentation, and texture to evoke a haunting sense of memory—one that is at once deeply personal and collective, fragile, and enduring. The film, constructed from timeworn VHS footage from the mid-to-late 1990s, captures pre-wedding family rituals in Kosovo. Family gatherings culminate with an evening feast where a man burns his handkerchief, a custom that steps him to married life. Celebratory fireworks accompany the soundscape. Or are they gunfire and bombardment from a not-so-distant future? The looming presence of war subtly infiltrates these intimate moments. The yellowish tint of the footage, a testament to the passage of time that marks the tapes, echoes the creamy yellow paint of the filmmaker’s parents’ house. This color, at first a marker of familial happiness and stability, gradually takes on a more ominous tone, hinting at the foreboding tragedy to come.

Sefa’s film explores the textures of memory through the archive, repeating and reconfiguring fragmented voiceovers. Refrains like “She was so happy that they married her here, in this house” and “He wanted to be a hero” return repeatedly, laying new meaning in each repetition. Repetition, Jacques Derrida says, lies at the heart of the archival process, but it is also its fever and destruction. Here, repetition is a double-edged sword: it allows memories to persist and be revisited, yet it also highlights their gradual disintegration and need for revisiting and reinterpretation. The film never explicitly reveals the catastrophe that followed these family celebrations, the war with the Serbian troops that took the lives of thousands. However, the constant, rhythmic return to such phrases, disembodied voices, incomplete sentences, and misremembered events imply a trauma that can neither be entirely forgotten, even when recalling the happy days. The decaying tapes, much like the memories they contain, are fragile and distorted, yet they persist, stubbornly resisting oblivion. With its hypnotic approach, Like a Sick Yellow invites the viewer to engage not just with the content of those memories but with their form—how they are constructed, deconstructed, and wrinkled by the passage of time.

In Tell Me a Poem, directors Elena Chirila and Ana Gurdiș craft a visual and poetic narrative of Chirila’s journey to freedom from a psychologically abusive relationship through the use of fragmented memories and associative imagery. The video poem weaves together elements of a personal diary with the fluidity of poetry, tracing the filmmaker’s evolution from childhood innocence to the uncertainty and the pain of a repressive relationship and finally to the strength found in reclaiming her voice.

Early scenes of VHS tapes from the protagonist’s childhood are abruptly halted as the abuse begins. The final shot of Chirila as a little girl performing for the camera is tilted sideways, disorienting the viewer and symbolising the significant rupture in her life. This visual disruption not only reflects the chaos of her experiences but also serves as a poignant reminder of how childhood innocence can be shattered in an instant. How do you remember that which you want to forget? Or how can you forget that which you no longer wish to remember? The only visual representation of trauma relies on metaphor, employing images of dark, cloudy skies and deep, flowing waters to reflect the protagonist’s turbulent inner world—dark, viscous river currents swirling in an almost hypnotic rhythm, occasionally punctuated by flashes of light on the surface, all evoke the emotional turmoil of her youth.

The room with a view of the river, possibly shot during the ECHO III residency in Bucharest where this film was conceived, allows for a metaphorical dive into deep waters, or “heavy waters” even, as French philosopher Gaston Bachelard calls them in Water and Dreams. He refers to Edgar Allan Poe’s poetry, where water suggests transformation and a passage through uncertainty. In the film, the river’s constant flux invokes the filmmaker’s attempt to navigate her memories. Its elemental texture, seen in lengthy closeup sequences one can almost touch, ties the protagonist’s healing to the larger, universal flow of life’s cycles—pain, repression, and eventual liberation. In this sense, the river becomes a cinematic embodiment of time where memory flows, waiting for a poet to interpret its meaning. This layered use of water imagery in free associations elevates Tell Me a Poem beyond the personal narrative, turning it into a meditation on the collective experience of repression, domestic abuse, and healing.

© Tell Me A Poem (Elena Chirila, Ana Gurdiș, 2023)

Collective memory matters to Ana Hušman in her EFA-nominated experimental short I Would Rather Be a Stone, which explores the interplay between landscape, memory, and the invisible yet powerful forces of time that shape both. In it, a calm voiceover often refers to “Little Jela”, who embodies the women in Hušman’s family and whose beliefs and words become a meditation on the experiences and stories embedded in the neglected Lika region of Croatia. The harsh living conditions, shaped by the barren land, the aftereffects of World War II, and the present human exploitation are mirrored in the sparse, textural force of the images. The mixture of 16mm and digital footage immerses the viewer in the region’s rugged terrain, its rocks and quarries standing in for the endurance and perseverance of its people like Little Jela and Manda in the face of the unforgiving passing of time.

The slow-moving imagery of lichen-covered stones, rocks, and minerals suggests a deep, geological time that outlives human narratives. The camera lingers on macro shots of earthly surfaces—stones, dried leaves, flowers, grass, and fruits hanging heavy from branches, rain droplets suspended from twigs—each detail captured with textural intimacy. They are interwoven with closeups of family photographs, layered through multiple exposures, creating a palimpsest of personal and geological memories. Little Jela’s quiet wish, “I want my soul to go into the stone when I pass,” fuses the human with the nonhuman, as if memory itself is as ancient and resilient as the rocks. Maybe memories are elemental, too.

The film culminates in a powerful long take of melting rocks, a chemical reaction that slowly disintegrates the stones, echoed later when a rocky hillside is blown apart with dynamite, filling the screen with clouds of smoke. They seem to signal a disappearing landscape that parallels the fragility of human recollection. In Hušman’s film, the earth itself is as alive with memory as the human stories it holds, where both personal histories and natural forms meld, fade, and reemerge in new configurations.

In such a complex multisensory cinema, the spectator exists as a bodily being, invested optically but also acoustically, senso-motorically, spatially, and affectively in the textures of memories. The camera is more than a passive observer; it becomes a participant in the sacred exchange, a conduit through which the viewer experiences the layered depths of time, remembrance, and spirituality.

Mentioned Films

Light of Light

by Neritan Zinxhiria, Greece, 2023, 12’

The hermetic landscape of the untouched monastic state of Mount Athos has remained unchanged since Byzantine times. Neritan Zinxhiria uses some of the 3000 preserved photographic plates made by one of the monks 90 years ago and his new Super 8 recordings to bring the past back to ghostly, languid, and intangible life—a meditative journey through space and time, all in stunning black-and-white.

Quadrant

by Slava Doycheva, Switzerland, 2023, 8’

Four quadrants: four attempts to dissect a found footage and lay bare a recent cancer diagnosis.

Like a Sick Yellow

by Norika Sefa, Kosovo, 2024, 23’

We’re observing prenuptial family rituals on degraded VHS somewhere in suburban Kosovo, as a woman’s voice repeats: “She was so happy that they married her here, in this house”. A heavy cloud of war looms in the near distance.

Tell Me a Poem

by Elena Chirila & Ana Gurdiș, Romania, 2023, 11’

The sequences of a personal diary, highlighting the child-adult evolution, accompany the viewer on a journey marked by uncertainty, helplessness, and self-doubt, which eventually leads to escape. The video poem oscillates between poetry and documentary, emphasizing a woman’s struggle to free herself from repression and regain her voice and strength.

I Would Rather Be a Stone

by Ana Hušman, Croatia, 2024, 24’

Through observing the landscape and models of cohabitation between living and non-living entities, Croatian experimental filmmaker Ana Hušman, examines the ways in which memories are built and narratives formed. And also how they disappear and fragment. A caring cinematic homage to female members of Hušman’s family, as well as to Lika, a neglected, sparsely populated region from where they originate.