Mirror Muscles

On Cinema’s Ideal(s) of Masculinity

Expectations of masculinity permeate today’s visual culture, creating pressure and exclusion for all, as illustrated in Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur’s short film programme “He’s Got the Look”.

The body is a temple, but temples are places of worship: we look at bodies, we desire bodies, we celebrate bodies, be it our own or those of others. All we’ve ever wanted is to look good naked, hope that someone can take it. God save me rejection from my reflection, I want perfection, sings the poet (Robbie Williams) about our innermost aspirations, in his fittingly titled “Bodies”.

If in her seminal work Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Laura Mulvey talked about “to-be-looked-at-ness” as a designated voyeuristic function for women on screen, the “He’s Got the Look” programme at last year’s Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur, curated by its festival director John Canciani, reverses the gaze to investigate the many ways in which we cast eyes on male bodies. Ranging from personal stories of sexual and queer awakening to comical yet poignant takes, the shorts in this programme frame the male body as a canvas for projection and objectification, but also as an instrument of labour—for the bodybuilding artist as much as for the sex worker.

For a long time, all throughout classical antiquity up to the Renaissance, from your Greek gods to your Davids, the (naked) male body has been a most common image in art, often associated with a notion of idealised athleticism. A plethora of sculptures and paintings have been sought to revere form and muscle, be it, say, the athletic body of the Discobolus or the enduring, martyred physique of Saint Sebastian. More recently, however, cinema has proven to be a more prudish medium—or, rather, one of sexual imbalance: how many naked male bodies do we see on film, really? It’s always been somewhat bitterly amusing just how often we’ll see a nude woman on screen, and how rarely you’ll find a scene depicting even the vaguest reference to full-frontal male nudity. The naked male body will only seldomly pop up on the screen, because to be gazed upon means to be vulnerable and exposed, and that might just upset the unwritten rules of power. To put it differently, being gazed upon is simply not “masculine”, because, to return to Mulvey’s observations, in cinema, men do the looking, not the “being looked at”.

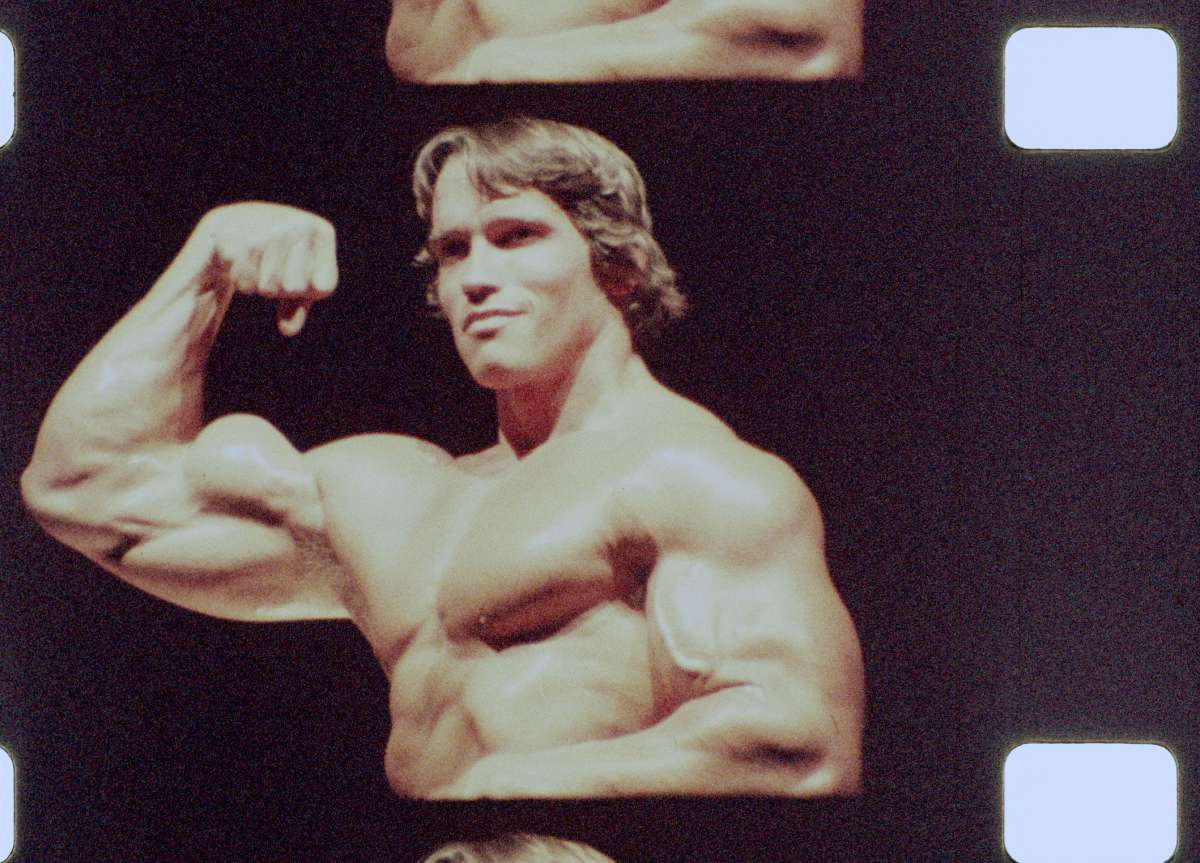

Picking up on these classical understandings of the male body throughout history, Babeth M. VanLoo’s Arnold Schwarzenegger – The Art of Bodybuilding (2020) offers an insightful account straight from the horse’s mouth, the horse in point being perhaps the most recognisable “peak male form” in recent history. The footage that VanLoo shot during the 1970s at the Mr. Olympia Bodybuilding Contest ends up being an unexpectedly theoretical report about bodybuilding as art. With a few references to Ancient Greek athleticism, Socrates’ Phaedrus, and Leni Riefenstahl’s renderings of Olympian bodies, Schwarzenegger comments on sport as an artistic pursuit, but more importantly, on the body as a form of art.

What the bodybuilder rightly points out is how, oftentimes, the obsession with one’s body is associated with vanity or with queerness. It’s a taboo to take the time to appreciate the male form, and demeaning or unserious for a man to work on his body, most often out of the irrational and toxic fear that the action might connote homosexuality. In turn, countering this narrative, Schwarzenegger argues for physical beauty as a vehicle that allows one to realise pure beauty. The soon-to-become Terminator actor pleads here for a destigmatisation of his art, suggesting that you can admire the male body without a sexual connotation. Instead, muscles and nakedness are to be understood as forms of artistic expression—in the gymnasiums of Ancient Greece, to be nude (gymnos) was simply what befitted the athlete.

The sound in VanLoo’s Schwarzeneggerian treatise on body and mind is, however, out of sync, with the bodybuilders’ musings also presented as text on screen. While this enhances the essayistic “serious text” quality of Schwarzenegger’s considerations, it also allows for a more comical interpretation. Of course, the footage could have very simply been recorded as such, with sound and image on separate tracks. Yet, at times, it feels like the bodybuilder might have been dubbed over, with the filmmaker planting these grand, philosophical references herself. This funny impression might only reveal our bias: if we do not expect the Austrian talent to be speaking with such a level of perception, then it would be because we have been preconditioned to look at bodybuilding as a form of brain-dead and steroid-fuelled pageantry. Whether parody or an actual piece of archival footage (as it is described in the Winterthur programme notes), VanLoo’s film is particularly enlightening in that it goes against what has been the common image of Schwarzenegger in popular culture as the mere “I’ll be back” muscled himbo.

Arnold Schwarzenegger – The Art of Bodybuilding (Babeth M. VanLoo, 2020)

If Schwarzenegger attempts to refute a perceived fear that looking at male bodies is synonymous with queerness, Gods of the Supermarket (2022) takes this queerness further, only to reclaim it from a personal viewpoint. From banal adverts and pictures of male models to internet media and gay porn, Alberto Gonzales Morales goes deep into the mainstream visual constructs and projections of hypermasculinity that one interacts with daily.

Part a self-aware reference poking fun at the film’s DIY, terminally-online style and part a critical take on consumer culture, the title of this meme-filled endeavour is telling of its cheeky mundanity; the video essay draws its juice from outside of cinema, from the insidious oversaturation of our everyday “supermarket” lives with images of hot male naked bodies. From the randomest stock photo on an underwear package to pervasive images of pornography, Gonzales Morales investigates these icons of virility as they seek not only to entice the consumer but to create certain visual narratives that dictate which bodies are the desirable ones. The stock images for these products—seas of hairless athletic bodies—automatically invalidate otherness and difference and impose themselves as the definition of masculinity that one should aspire to.

Commenting on the ensuing unrealistic standards and body-dysphoric anxieties that they create, Gonzales Morales brings his film into autobiographical territory as he reflects on his personal relationship with the male body as a gay man. Gods of the Supermarket frames the male body as a forbidden fruit when the director reminisces about these trivial images as proxies for his own sexual awakening. The trivial or the pornographical serves this function because the mainstream will not allow it—not only are queer sexual representations so often absent from it, but cinema generally quakes at the thought of subjecting the male body to projections of desire and pleasure.

Lovisa Sirén’s Audition also looks broadly at gender dynamics, but focuses on a more specific situation. As a director is looking for male actors to star in her film, the roles are reversed. If the film industry is filled with intrusive directors and exploitative casting stories, in Sirén’s film, it is a woman who asks the pushy personal questions and oversteps her actors’ boundaries by asking them to take their shirts off. At the other end, however, the actors themselves are very conscious about the kind of masculinity they are projecting, and get upset if not aggressive when that is potentially being challenged with intimate interjections.

As much as the director in Audition is being forceful and inappropriate in her questioning and demands, the actors’ reactions also point towards a form of the same machismo that encourages men not to speak about their feelings on and off screen, especially not in front of women. In the actors’ visible discomfort, one can perhaps spot a trace of their disrespect towards the female director in front of them. More than a study of audition-powerplay, Sirén’s film goes to show how women in the industry may still face distrust even when in positions of more apparent power, like that of the director.

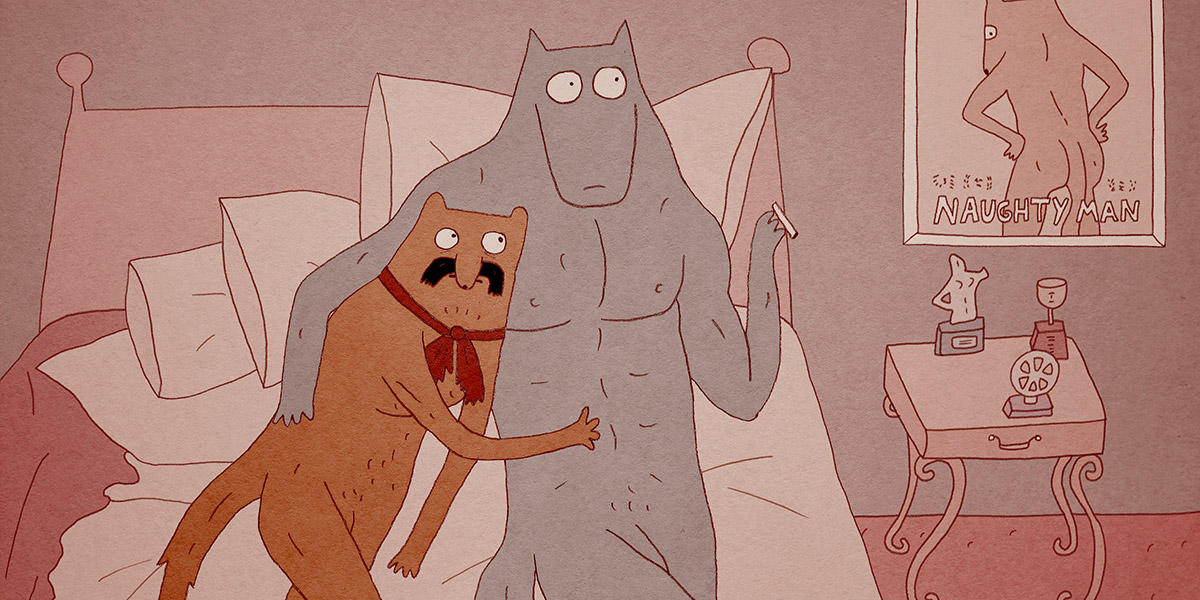

Industry and labour are also key themes for the last two entries in the programme: Chintis Lundgren’s Toomas Beneath The Valley Of The Wild Wolves (2019) and Enrique Pedráza-Botero and Faye Tsakas’s Alpha Kings (2023), a thematic pair brought together by their shared interest in masculinity and stereotypes in relation to sex work. For a start, it’s worth noting how crucially different these films are from the often extra-fetishistic depictions of women’s sex work in cinema, even from the more “I’m on their side”, pretend-nuanced ones like Sean Baker’s Anora (2024). From tongue-in-cheek animation to observational documentary, both question stereotypes rather than perpetuate them.

Toomas Beneath The Valley Of The Wild Wolves (Chintis Lundgren, 2019)

Lundgren’s animation looks at a wolf plumber stumbling into sex work as all his clients keep suggesting that they need a fix more urgently than their sinks. Blessed with a six pack and other drool-worthy qualities, Toomas’s increasing objectification—mostly from women—is explored with humour, poking fun at the idea of conventional hunk masculinity, but also deconstructing certain expectations about a “gigolo’s” life. Toomas has a family, and his new line of work comes out of necessity to support them. Crucially, his wife Vivi, who has her own arc of sexual revelations as she discovers her dominatrix side, is very accepting, despite all the shame her hot wolf husband is carrying. With sex work often being coded as a female activity, Toomas Beneath The Valley Of The Wild Wolves reverses the roles and points out the discrepancies in bias and stigma, while never really losing sight of the damage caused by reducing someone (some wolf) to a sexual object. Underneath Lundgren’s absurdist tone lies the commentary that men are not expected to be subjected to oversexualisation, so their problems in this matter are often easily dismissed or overlooked.

At the other end, Alpha Kings looks at the more recent contexts of internet sex work, as it follows a group of young men popular on OnlyFans and similar streaming websites. What the documentary observes is just how much the definition of sex work has changed today, and how these platforms and screens mediate power, play, and sexuality when the client never has to even show themselves. At night, these men perform the roles of alpha kings, prompted by their fans and users to act domineering in exchange for money. During the day, they are your usual 20-year-olds, mostly talking about the economic aspect of their work and how it has become a more viable option than college. The film doesn’t comment on these motivations or their practice, and it doesn’t kinkshame either. It highlights, instead, the stark difference between an offline life and an online life—here also a work life.

Notably, their work doesn’t include any kind of nudity, but rather a performance. Their roleplaying, therefore, illuminates a particular definition of “alphaness”—they are paid to project an enhanced and aggressive version of masculinity that seems desirable, but that contrasts profusely with real life and real expectations. Masculinity is here an idea or a stereotype, a blown-out fantasy and projection.

In contrast with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s pure aspirations about his art, these later approaches to the body and sex seem dirtier and less permissible, specifically because they deal more readily with desire embedded in the looks. Cinema mostly shies away from presenting men as the objects of desire because that would redistribute the power already in place: if to film means to shoot, to be gazed upon means to be preyed upon.

Despite this apparent shield, these shorts show that men are never spared from processes of projection and objectification. Expectations of masculinity and “looking good” permeate the visual culture of today in many ways—men are not safe from it and the unwillingness to recognise the damage caused by unrealistic, one-dimensional and heteronormative definitions of masculinity causes harm to all, men, women and other folk alike. To insist on a standardised image of masculinity, or femininity, for that matter, means to create pressure and exclusion, especially when that image is but an unreachable ideal sold as an imperative.