Playing Along

Anna Martí Domingo on Boys

Now nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025, at the heart of Anna Martí Domingo’s Boys is the gradual construction of masculinity in its toxic iterations.

On the beach by the Balearic Sea, a group of boys are playing games—the game of pushing each other, to be more precise. This opening scene of Spanish filmmaker Anna Martí Domingo’s short film debut, Boys (2024), seems rather casual; it may just be an ordinary snapshot of a summertime familiar to many youngsters. Yet, by the end of the film’s fifteen-minute runtime, the naïve look of the games can no longer conceal their micro-violent nature. Underneath the boyish expressions and their frisky and innocent behaviours, lies an equally familiar trait: the gradual construction of masculinity in its toxic iterations.

Speaking about the impetus of her film, Domingo shares how important it was for her to represent violence that is small and subtle. “Nothing really extreme has to happen, yet, by accumulation, you get this feeling of anxiety,” she says. This iteration of uncomfortable subtleties is achieved through the script’s pulsating composition, where each little physical jest of the boys immediately cuts to a non-violent act, then folds into another game. After some raucous rounds of tussling, the boys are silently sunbathing in the sea. What follows the absurd still frame of them jamming up and napping in the courtyard, is when one of the boys, Teo, and his playmate, Oscar, bite into the other’s food and bump into each other, habitually. In tune with this rhythmic structure, this supposedly harmless everyday playfulness resonates with the film’s original Catalonian title, Nens, denoting “boys” or “kids.” The filmmaker explains it invites the association of, “‘Oh, they’re just boys and playing, they’re kids.’” Even when the situation becomes slightly violent, “to the point that maybe we should say something, the typical reaction would still be ‘no, it’s okay, they’re just kids, they’re playing,’” she describes. Besides, setting the story in summer means there are more narrative opportunities to explore further what may be simmering underneath the experience of seemingly carefree days. “Since these groups of eighteen-year-old boys may only meet in summer, it is the perfect environment to show these day-by-day dynamics because that’s when you can play all the time.”

In the short, the boys almost always move as a herd, making it tricky to tell them apart. This group portrait is central to the film, as it can most adequately “represent the hegemonic masculinity,” asserts Domingo. However, the filmmaker knew it was equally important to show how the group separates itself from the most toxic ways of masculinity. We see the boys take care of each other by hugging, kissing on the cheek—acts that the director describes as “a bit queer in some way.” Furthermore, they collectively bail on the familial gathering dinner, with their resignation exposing the cringeworthy absurdity of those middle-aged men at the table. Nonetheless, this distance from the hegemonic machismo fails to justify itself whenever the boys start to play among themselves. “In this group I constructed, it wouldn’t make sense if the boys hit each other without a reason.” Game and play, then, become the perfect excuse for the boys to be violent. When they’re jostling against each other, shooting the friend’s butt with fake pistols from afar, or slapping the opponent’s face when losing the move in chess—all rules are self-made; one grants a certain degree of impunity to these actions when describing them as game, leisure, or joke. These microaggressions take place in what Domingo describes as “the innocent space,” perpetuating the “depoliticisation” of everyday actions, even when they become critical and inappropriate.

This continuous exemption the boys receive is noticeable in all the male characters in the film. “The gradual process of these behavioural patterns building up to the construction of masculinity is everywhere, all the time,” Domingo stresses. From Teo and his group to Teo’s father and his male friends, to the old man Joan in the amusement park, who barely appears yet loudly and clearly remarks on the boys’ “girl-like” shooting skills—the different generations present in the story, are all in the same context, part of the cycle of the manly masculine behaviours built based on the binary heterosexual norms. In the film, as in life, men align themselves with those of a similar age; and inside their groups, “they are also building their identity, like masculinity in its microform.” This socially understood, accepted, and endorsed masculine trait is transversal throughout the generations, proving Domingo’s thesis that the impunity benefited from the colloquial use of the game is, in her words, “not age specific, but gender specific.”

When consequences of micro-violence can barely be immediately calculated during everyday gameplay, they are, nevertheless, not completely dismissed and would send out distressing signals. Perhaps one of the most contrasting sequences of the film is when Teo goes to the kitchen and meets his father alone there in the middle of the night, after a scene where Teo displays worrisome when the group jointly (and with the rest of them, jokingly) witnessing Mauri climbing up the rock for his sleepover. The economic exchange of lines between the father and the son—“What are you doing?” “I’m thirsty. And you?” “I can’t sleep,” “Good night.”—refutes any opportunity to communicate feelings or emotions, despite the undercurrent of mental struggles they might be experiencing. Domingo comments on this particular scene that “the fact that the characters are emotionally incompetent, because they haven’t been educated in being emotionally intelligent, makes them just so distant, even though they’re in such a small room.” The co-presence of Teo and his father in silence, says the director, “is perhaps one of the most obvious scenes demonstrating how hegemonic masculinity expresses itself in ways that aren’t talking about emotions.” As a result, the film suggests the reinforcement of machismo culture and the simultaneous widening of the generational gap due to the restrictive emotionality.

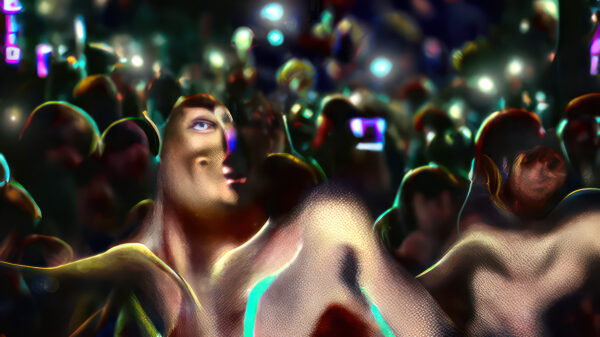

Boys (Anna Martí Domingo, 2024)

Scenes featuring female characters in-between Boys, according to the filmmaker, are another key to the short. Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, girls take up the main role of observing the everyday physically violent gestures shown in disguise of boys-having-fun. “If I have to name, not a point of view, not a protagonist, but a narrator of this specific part or expression of masculinity in this short, it would be the girls and women, no doubt,” she says. Female characters, as this collective narrator figure, do not neglect that bizarre something brewing in the innocent space of the boys’ games, even though the girls might not be able to comprehend exactly what is happening. Through the gaze of the female characters—from the little girl passing by the beach in the opening scene to the sister drying her laundry and later with her female friend unwillingly dragged into the chess game—we mostly get the sense of confusion and indifference towards the boy group. “Female characters always observe from this background—a space they are obliged to occupy, which is never the centre. I think by staying and observing in that space, it makes them intelligent, like ‘we are over it.’” Portraying these female characters in this particular way has to do with the director’s own experience. Domingo shares that she’s been “the girl who has always played among the boys, yet it was always very clear to me what space I should occupy.” From that periphery she was relegated to, the director had the chance to observe the played out physical acts, which she only understood later as a grown-up to be “the core element of violence in constructing this hegemonic male gender identity.”

Cinematically, the subtlety of Boys is achieved through its camerawork with selective yet poignant use of focus. When Domingo opens up about her stylistic reference being Beau Travail (1999) by Claire Denis, “in terms of the beauty in the movement of the body,” I recall the opening scene of the boys by the beach. That sequence embodies a queer choreography—not in the sense that it determines the characters’ sexuality, but that the way they experience proximity is dominantly channelled through bodily interactions. The director also mentions that her search for more references was rather in vain when it comes to the theme and the structure, as she realised that in most films addressing masculinity, especially the ones written by men, the sexual representation—often in queer sexualities—overtakes the spotlight, “I have only noticed very few that address masculinity because of masculinity, and that’s it.”

While threading her own path in terms of representation, the director has, however, left us a hint concerning the broader social-cultural landscape that shapes one’s routineised micro-violence. When I hastily throw out the assumption that the universality of the excessive masculinity seems to make it possible to name the locality in the story as any coastal town, Domingo points out that the decision of the location—Calella de Palafrugell—carries a deeper meaning. “The town is well-known in Catalonia; people living there can no longer pay rent because it’s full of tourists in summer,” Domingo says to me, “I wanted a place that’s very much gentrified because it’s part of the problem when talking about norms and hegemony.”

Approaching the end of the film, the boys return to the beach the following day and try to find Mauri, who is supposed to sleep overnight on the rock as his penalty. The audience stays with Teo, who is getting anxious when his friend’s phone number won’t dial through, “we could actually have been with anyone in the group, as they are all scared at that moment,” notes the director. Have the boys finally taken the game too far? We stay with Teo in that worried feeling; he seems to understand something, as we see traces of unease revealed through his eyes. But as Teo and the group (and we) are relieved to see Mauri reappear, teases and jokes fly around the boys; they get into the water and, one minute later, hop onto one another again, like from the start. When asked about the ending, Domingo says it was written as such very early on and never changed. “It was clear to me that I did not want a happy ending. In a fifteen-minute short, I won’t get a guy to understand his conditions and suddenly go, ‘guys, you have to stop!’,” she adds. Boys leaves us with the group in this “infinite loop” accumulating micro-violent masculine performances; as we see it all unfold from afar, the boys keep playing along.

Boys won the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025, after being nominated at Kortfilmfestival Leuven by Khushi Jain, Rafael Fonseca, Tianyu Jiang, Lina Heimann, Ilo Tuule Rajand, and Klara Jovanov, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #6.

The New Critics & New Audiences Award is a project by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END), hosted by Talking Shorts, and funded by the Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. With the support of This Is Short.