Putting The Sex Back In Homosexuality

Bruce LaBruce On “Queering” Art As A Political Act

Canadian artist, writer, photographer, and filmmaker Bruce LaBruce has been trailblasing sexually explicit queer cinema for decades. From his catapulting debut in 1991, No Skin Off My Ass, over the darkly satirical sex comedy Hustler White (1996) and hardcore gay porn The Raspberry Reich (2004) to horny zombies roaming the streets of Los Angeles for dead bodies to fuck back to life in L.A. Zombie (2010): LaBruce is a cult sensation.

“I remember when I saw Robert Altman’s That Cold Day in the Park on TV late one night. I was really stunned by it, and I thought to myself, “Is this what pornography is?”. The relationship in the film between the middle-aged spinster and the hustler, whom she meets in the park and ends up locking up in her bedroom in a kind of twisted psychosexual fantasy scenario, really stimulated my budding sexual imagination,” tells the artist, generously sharing insights from his extensive artistic career on a Zoom call from his home and writing retreat in Toronto.

Like the sexual representations in his films, LaBruce places no limits on form, moving fluidly across different media, genres, and formats. The 27th edition of Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur screened a selection of short films from different periods of his career, highlighting the filmmaker’s incendiary push against sexual norms. His resistance to aesthetic conventions and general mainstream respectability throughout his expansive line of work is, of course, decidedly queer.

LaBruce started making sexually explicit queer punk films with his Super 8 camera in the mid-1980s during his years as a graduate student at York University. Around the same time, he co-instigated the underground fanzine J.D.s with fellow Torontonian artist, filmmaker, and musician G. B. Jones. The zine ran for eight issues between 1985 and 1991. “J.D.s was kind of the original Queercore fanzine. It spearheaded the queercore movement,” says LaBruce. The zine provided an aesthetic outlet and meeting place for unassimilated queer punk rockers with a shared distaste for mainstream culture and liberal gay politics of social integration.

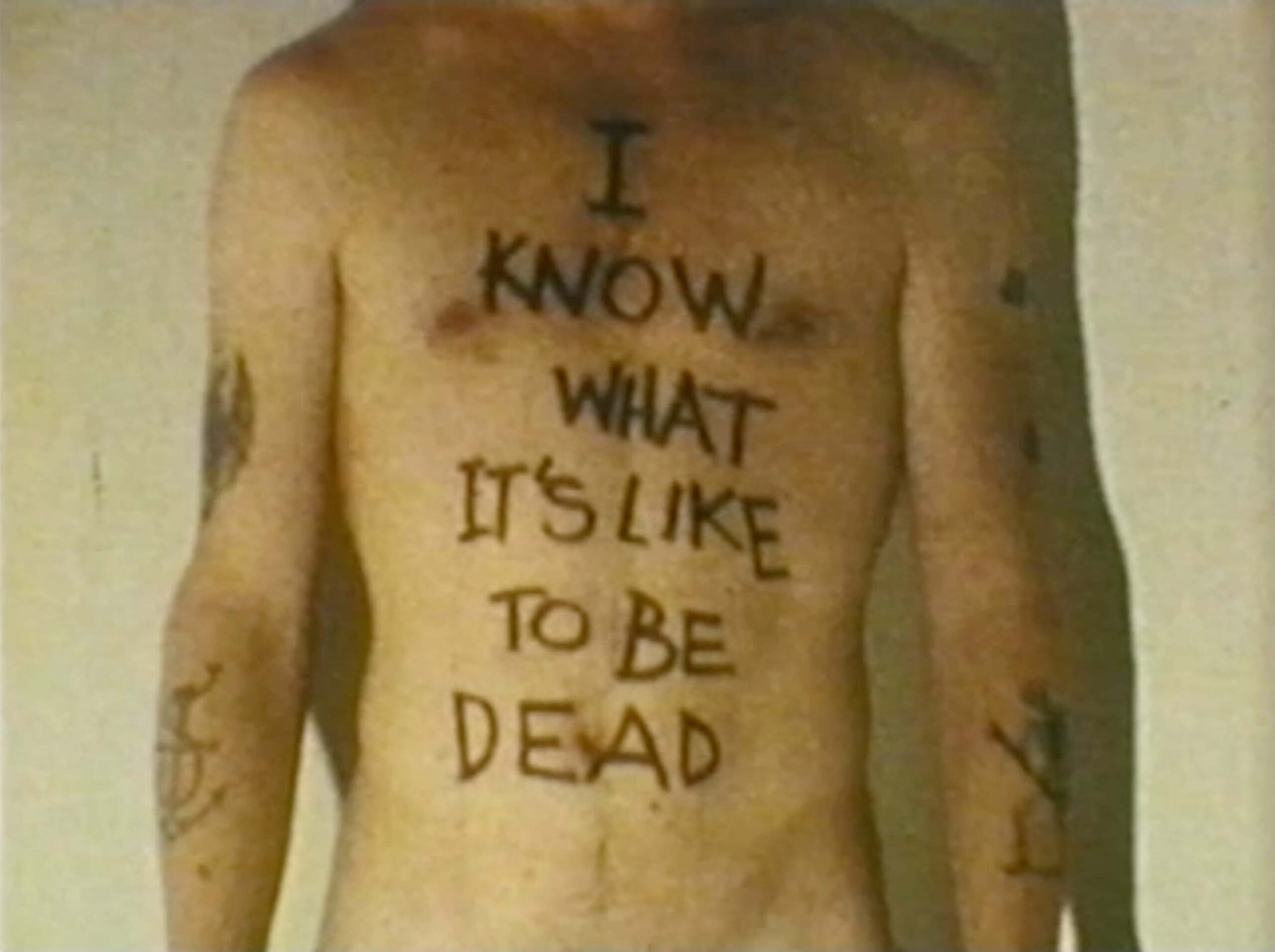

One of the early Super 8 short films, I Know What It’s Like to Be Dead (1987), which was part of the Winterthur selection, utilises a similar collage aesthetic to the slapdash, cut-and-paste style of J.D.s. “It really comes out of the same fanzine process,” LaBruce says. “Part of [it] was just to document all the crazy things that our friends were doing. If they were going to get pierced or get drunk, eat dog food out of the bowl, or shoplift, we would document it. So, it’s partly like a documentation of a scene. But then I started constructing narratives from this personal footage and the found footage taken off the TV. I had a job at a late-night restaurant called Just Desserts, and I would get home super late, and there would be a marathon of Here’s Lucy11 A popular American sitcom starring actress and comedienne Lucille Ball, which originally aired on US television from 1968 to 1974. ↩︎ on television and I couldn’t get to sleep. I would just shoot it off the TV with my Super 8 camera.”

I Know What It’s Like To Be Dead

I Know What It’s Like to Be Dead amplifies some of the trademark aesthetics of the early films, being at once very personal with a documentary aspect, as well as formalistically experimental in that it plays with disjunctions between sound and image. In the film, LaBruce is dragging himself like a zombie throughthe tunnels, trains, and escalators of Toronto’s subway system. In some ways, the film can be seen as a precursor to his trilogy of Zombie-porn movies, which to date includes Otto; Or Up with Dead People (2008) and L.A. Zombie, but it is also a melancholic response to the HIV/AIDS crises of the time, dealing with the affective entanglements of fear, paranoia, grief, and sadness in a characteristically punk camp manner. “This is the mid-to-late 80s, and we were living with this threat of annihilation, being stalked by this fatal disease. It was terrifying watching people around you die. In the film, I deal with it in a kind of lighthearted way. I go to the hospital and have this dream while I am being operated on, and in my dream, I see the Rock Hudson-Linda Evans famous kiss from Dynasty, which at the time was extremely scandalous. There was a lot of fear and paranoia. People thought you could contract AIDS just by touching a gay person. That scene was like a horror movie.”

The infamous scene between Evans and Hudson, in which they kiss with mouths closed following the public disclosure of Hudson’s diagnosis of AIDS, is repeated several times during the film. Its inclusion exemplifies the filmmaker’s preferred methodology when working with existing source material, whether it is incorporation of found footage or remakes, like his recent feature Saint-Narcisse (2020) or the upcoming The Visitor, a loose reimagining of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Teorema from 1968. “It’s a process of queering. If the source material isn’t overly queer, then I queer it, which is a political act in itself.”

At the end of I Know What It’s Like to Be Dead, LaBruce is seen performing a striptease to the sound of Nancy Sinatra singing, “And love is a stranger who’ll beckon you on / Don’t think of the danger, or the stranger is gone” in You Only Live Twice (1967). The act of striptease, at once youthfully naïve and sexualised in its expression, embraces queer sexuality and becomes a way of shedding not only inhibition but also the fear and paranoia about HIV/AIDS. LaBruce explains, “The scene is kind of the typical dream or trip where you die, and then you are resurrected at the end. Striptease became a way of embodying my homosexuality, which I repressed for so many years.”

This liberation aligned with the declared ambitions of LaBruce, and the Queercore movement at large, to “put the sex back in homosexuality.” The film was made during a time when sexual repression was being unprecedentedly embraced by both the conservative right and the anti-porn feminists on the left, who stood united in their attacks on what they perceived as sexual perversions, which generally meant anything other than genital (p-in-v) heterosexual intercourse.

However, the sense of political potential in liberating repressed queer sexuality doesn’t just reveal the film’s socio-historical context, but also the influence of progressive thinkers like Wilhelm Reich and Herbert Marcuse, whose work LaBruce encountered as a grad student. Originally planning to be a film critic, LaBruce studied under gay film studies pioneer and film critic Robin Wood whose teaching and writing were highly influenced by the psychoanalytic theory of Freud, Marcuse, and Reich. “I remember taking a grad course on psychoanalysis and feminism; I was the only male in the class.”

Reich was especially important to Wood. Contrary to his teacher Freud, who saw sexual energies as destructive forces that needed to be bridled through sublimation to keep society well-adjusted, Reich advocated for the liberation of all consensual sexual expression. And like Marcuse, he saw the politicisation of erotic desire as the best defense against social suppression: a notion that has been continuously reflected in LaBruce’s work. In Raspberry Reich from 2004, he quotes both Marcuse and Reich directly, in addition to naming the film after the latter. As it irreverently toys with Reich’s view of sexual oppression as a dangerous instigator of fascist behavior, the film frequently intercuts its plentiful pornographic representations with tongue-in-cheek militant slogans like, “Heterosexuality is the opiate of the masses!”

A similar queer play with psychoanalytic thinking also shapes The Bad Breast (2010). Here, however, it is another pioneer of psychoanalysis that informs the narrative: Melanie Klein, who rose to prominence with her interpretations of Freud’s work after his death. The film was originally part of the 2009 theatre project The Bad Breast, or The Strange Case of Theda Lange, about Klein’s life and theoretical writings and was performed at the HAU in Berlin and subsequently in Vienna. The film is composed of visual material shot for the theatre piece, which was later edited into a stand-alone piece.

In a campy, subversive spin on conversion therapy and in the formal guise of a lo-fi underground version of a Hollywood maternal melodrama, The Bad Breast centers on a neurotic mother who enlists the help of her repressed Kleinian psychoanalyst in hopes of turning her straight son homosexual. “We shot with a tiny Japanese toy camera with a plastic lens,” LaBruce explains. Admitting the process was “just really fun,” he continues: “The costumes were from the play. The idea was to make a Hollywood female melodrama but to make it on a very small, modest scale with this camera that created gorgeous images that look like Super 8.”

The Raspberry Reich

While most of the filmmaker’s feature-length work has found its audience in art house cinemas and in the film festival circuit, as well as in visual arts contexts (such as the 2015 career retrospective at MoMA), LaBruce has frequently come under fire for what he himself terms “working too much within the porn idiom.” In the Winterthur programme, Purple Army Faction (2018) represents his long-standing interest in using pornography for political purposes. The film, which was made for New York-based porn studio CockyBoys as part of an omnibus project of four thematically linked films called It Is Not the Pornographer That Is Perverse…, centers on a homosexual terrorist gang, committed to reducing the world’s dangerous overpopulation. Seeking to stop people from reproducing, the gang kidnaps unsuspecting heterosexual men and attempts to sway them into joining the homosexual cause by having sex with them. For LaBruce, “the film has the same spirit as my early Super 8 films. It’s a kind of cheeky allegory that is also politically charged. There is one scene where the actors are having sex at a remaining section of the Berlin Wall. It was very guerilla.”

Like in Raspberry Reich and the forthcoming The Visitor, Purple Army Faction repeatedly flashes parodically political slogans demanding queer sexual liberation, such as “Save the Planet. Go Gay!”, “Think Globally. Fuck Locally”, and “Make Gay Great Again”, over the screen during hardcore sex scenes. The effect is jolting: it undercuts sexual arousal through distraction and confoundment to detach one from pleasures of the flesh by engaging the intellect.

The use of distancing effects in pornographic scenes serves several political functions in LaBruce’s work, challenging both the propriety of professional filmmaking and the repression of explicit sex in mainstream media. He knows it is an unpopular choice to mix porn with politics, but maintains that this is precisely why it needs to be done: “Most people see pornography or explicit sex as something banal or a distraction, or something to be used to jerk off to. They don’t take it seriously. When you interfere with that by asking them to be intellectually engaged at the same time, they will get angry.”

By making the audience self-conscious about their own spectatorship and drawing attention to the mechanics of his sexual representations, LaBruce accentuates how we as viewers perceive sex: “I am pointing to the awkwardness and artificiality of it, or this idea that porn is supposed to be this fantasy of perfect sex, and kind of undercutting that. But also, how we can be seduced by it, and how it can be used as propaganda. Because it really works on the subconscious. I see porn as a collective subconscious.”