Re-Framing the Family Archive

Using Home Videos in Documentary Filmmaking

Family archives are a fruitful resource for filmmakers, exemplified in this year’s International Documentary Festival Amsterdam (IDFA)’s short film competition.

Before social media, families would document their lives through the creation of photograph albums, updating them after each of life’s big milestones. Then came home videos, which complemented these albums with recordings of school plays and family vacations. The art of collating and curating these items might seem anachronistic in our digital age, but most families possess some form of archive—whether that be a dusty scrapbook, a shoe box full of faded photographs, or a collection of old Super 8 movies. Anything that links them to their ancestors and helps preserve their family’s history will do. Although designed to entertain intimate audiences of friends and family, these archives have increasingly been used by filmmakers as a narrative tool for historical storytelling; with their amateur aesthetic becoming a shorthand for factual accuracy. But how reliable are these archives? Do they tell the full story, and what about the traumas of the past that mark and shape our lives?

Family archives can be a fruitful resource for filmmakers, providing a glimpse into the lives of ordinary people and bridging the division between private and public. But look closely at these images and you’ll notice a sea of smiling faces, with most of these photos and videos taken during birthdays, weddings, or religious holidays. It could be argued that they provide a false and superficial image of the family, erasing almost any form of conflict. These archives’ reliability was a recurring theme at this year’s International Documentary Festival Amsterdam, where multiple filmmakers exhumed the traumas that are obscured through the performative act of recording family histories.

During reunions or on cold rainy days, families would occasionally retrieve their photo albums and flip through the stiff plastic pages to reminisce about specific moments in their shared history. For many, this became a ritualised way of remembering the past, yet recent academic studies of family archives, such as Marianne Hirsch’s “Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory” (1997), suggest these snapshots present a misleading portrait of harmony and obscure any form of discord. Şirin Bahar Demirel applies Hirsch’s ideas to her own family archive in the poetic documentary Between Delicate and Violent, in which the Turkish filmmaker scratches behind the surface of her grandparent’s photographs to unearth their lost memories.

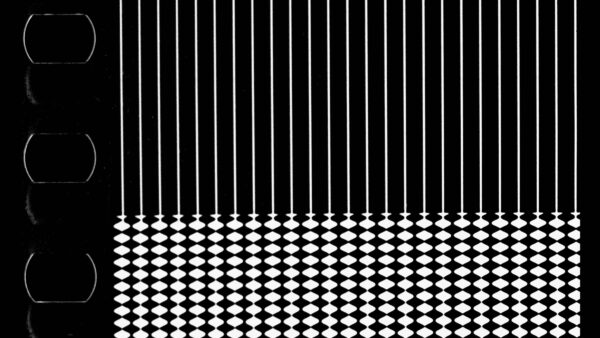

Similar to British artist Jo Spence’s Beyond the Family Album—a series of panels in which autobiographical texts, personal photographs, and press clippings combine to reconstruct the traumatic events often omitted from family photo albums—Between Delicate and Violent combines various techniques to explore what artists call “hand memory”: knowledge that isn’t stored in the brain but in the body, and is released when you start to paint, sculpt or draw. To this effect, Demirel starts the film by examining her grandfather’s paintings to see if she can ascertain anything from the brushstrokes that might explain his history of domestic abuse.

Like a box of photographs overturned, mixed around, and then tossed into the air, Demirel takes several images of her grandfather’s hands and magnifies them in an attempt to release the traumatic memories hidden within. She then goes about constructing her narrative like a police detective putting together an evidence board. Paintings are scratched, video clips manipulated and photos brought to life with animation as she attempts to recontextualise these artefacts to depict something closer to the lived reality of her grandparents’ lives. “I fill the ordinary photos of my grandfather with the emotions that I want to see in them,” she tells us through a voiceover. However, it’s unclear if it’s remorse she’s looking for or evidence of generational trauma that might explain his violent outbursts.

Demirel later applies the same approach to her grandmother’s embroidery to see if she can identify anything in her needlework that could pinpoint the moment late-onset schizophrenia took hold of her mind. The film’s difficult themes of domestic violence and mental illness are softened by Demirel’s playful use of animation. Drawings of hands appear against the sound of broken crockery, and in one moving scene, a hand-drawn version of Demirel’s grandmother walks across an embroidered tablecloth to illustrate her journey to the Bakirköy psychiatric hospital. These disruptions are like tears in the fabric of her family history, revealing new subversive meanings that weren’t visible in the original images. By actively shaping and contributing to these photos, Demirel demonstrates how the family archive is more than just a record of past events but a living, breathing object open to malleability.

Our Special Little Secret (Anna Hanslik, 2023)

The introduction of small-gauge film stock in 1923—often heralded as the unofficial birth of amateur filmmaking—facilitated the expansion of the family archive also to include moving images. However, it was the invention of more affordable video formats like VHS camcorders in the 1980s and MiniDV cameras in the 1990s that would lead to the widespread popularity of home movies, resulting in a generation of adults whose childhood memories are a pixelated blur.

Contrary to staged family photographs, these home videos present us with a succession of images and the opportunity for the idyllic image of the family to be ruptured, if only for the briefest moment. It could be someone turning away from the camera or refusing to be filmed. The camera still lies, but the spontaneous nature of these videos means that they can often provide a window into the tensions and conflicts that exist inside the family.

Families would occasionally organise screenings of these movies in their living rooms, huddling around a television to watch themselves take their first steps, get married, or celebrate the same birthday over and over again. But can these videos really resurrect the past? And how much past can a person bear? These are the questions proposed in Anna Hanslik’s darkly compelling Our Special Little Secret, which explores how home movies can obscure non-documented and often contradictory stories. An unsparing excavation of the traumatic childhood abuse that shaped her life, the film sees the French director—perhaps best known for her anthropological documentaries like The Hermit (2020)—delve into her own life story to examine the ways in which home movies can be both a source of memory and a way of forgetting.

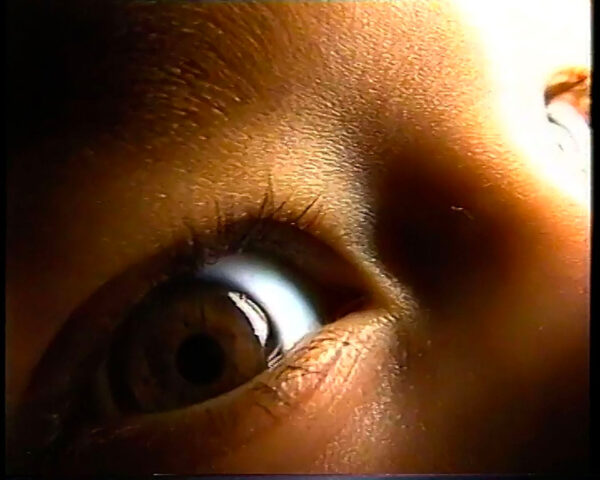

An unfathomably brave film about the internalisation of sexual trauma, Our Special Little Secret sees Hanslik review old camcorder footage from her youth in an attempt to make a connection between the frightened child of her past and the wounded adult of today. While this footage contains all the familiar accoutrements and markers of classic home movies— people acting silly in front of the camera, Christmas celebrations, and landmark occasions with family and friends—the result is a quietly devastating essay film that exposes how home videos like these can make memory formation problematic. As we observe footage of a family holiday Hanslik took with her parents when she was a baby, silent subtitles narrate her reasons for returning to these images and her desire to expose the emotions and incidents that videos like these systematically deny.

Home movies tend to have an affinity for children, and Our Special Little Secret is no different, with almost every shot featuring Hanslik as a child. From playing in the garden to bathing in a makeshift basin on the floor of her grandfather’s bathroom, there is rarely a moment when she isn’t the focus of attention. Like most family movies, the Hansliks’ ones are occasionally poignant and sweet but also full of clumsy closeups, laborious slow pans, and interminably dull shots of people doing nothing of interest. During these sequences, Hanslik’s narration fills in the gaps, explaining to us what was really going on in these moments. “I once asked my grandma, what are the secrets in our family?” she tells us. “It turns out I was the one with the secret!”

After this revelation, the film transports us to Thailand, where Hanslik and her mother moved during the late nineties to live with her grandfather. Illustrating how the process of investigating your past can be a trauma unto itself, Hanslik struggles to square her nightmares from this period with the smiling faces we see in these videos. It’s here that we learn that she was sexually abused by a member of her family. Scenes of Hanslik playing on a rowing machine whilst naked suddenly adopt a more sinister tone, whilst the film’s sparse sound design adds a further layer of unease. The scratched and faded audio of these decades-old tapes accentuates the disconnect between Hanslik’s recollection of these moments and the images of a happy family we see on the screen.

As is so often the case with home movies, it’s the man of the house (in this instance, Hanslik’s grandfather) who is normally handling the camera. As a result, he is almost entirely absent, except one scene where we see him lying on the sofa with Hanslik, tickling her under her pyjamas. We do, however, hear his voice off-screen. When Hanslik’s mother asks if she should undress and bathe with her daughter, he replies: “That would make Grandpa happy.” Moments like this make it difficult to understand how anyone could fail to spot these signs of abuse, but by reframing these videos, Our Special Little Secret demonstrates how the performative construct of the home movie, with its forced smiles and awkward jollity, allow abusers like her grandfather to operate in plain sight.

My Father (Pegah Ahangarani, 2023)

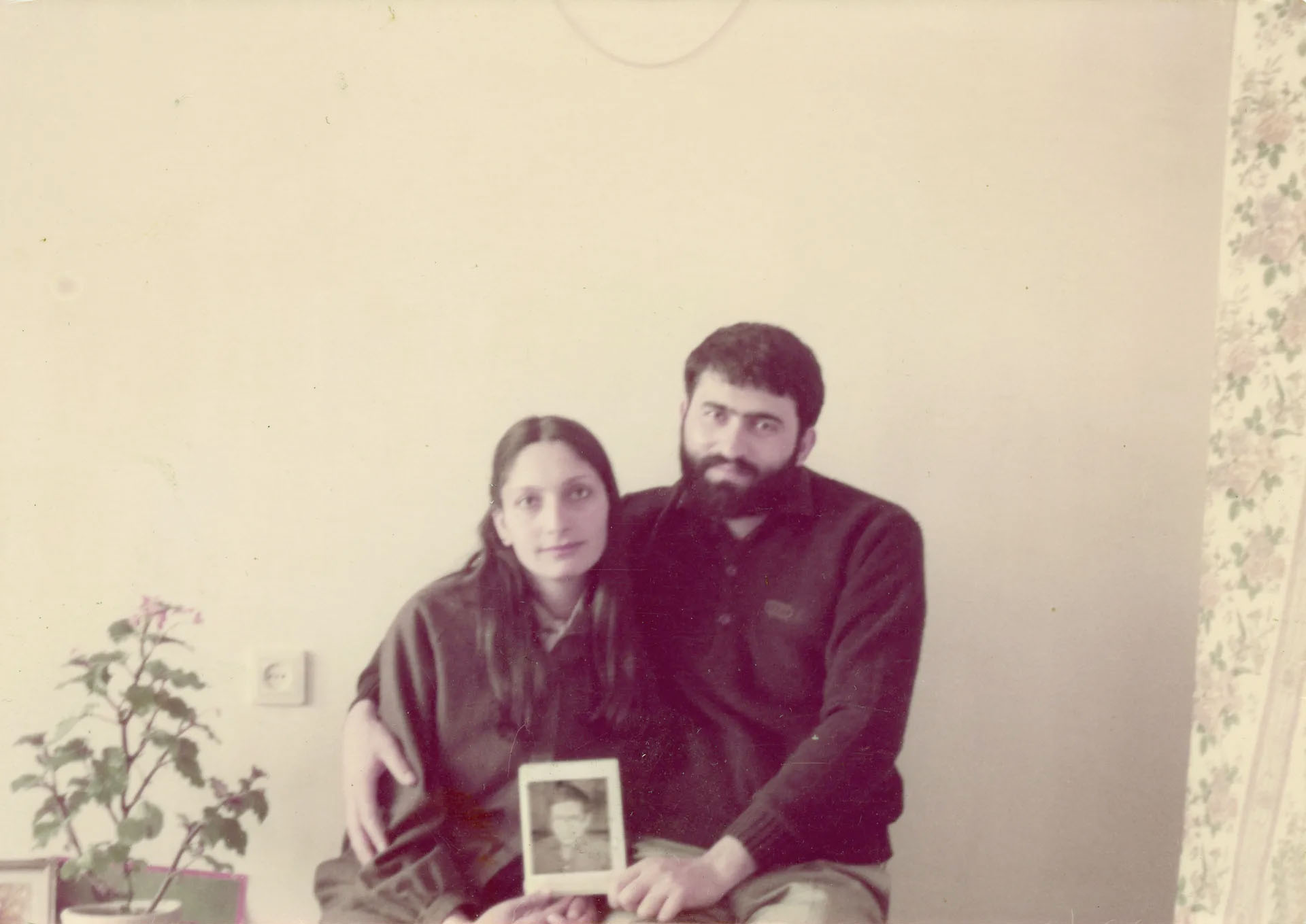

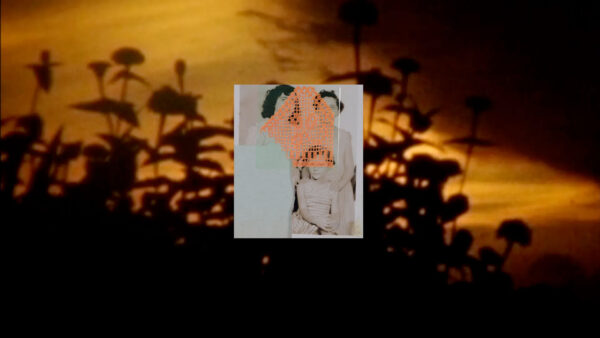

An equally personal response to archival materials can be found in Iranian actress, filmmaker, and activist Pegah Ahangarani’s My Father. A poetic documentary about the turbulent period that followed the Iranian Revolution, the film sees Ahangarani return to her childhood in an attempt to understand why the photo of the Ayatollah was replaced in the family’s Nowruz decorations by one of another man. A spiritual successor to her 2021 film I am Trying to Remember about a family friend who disappeared shortly after the Revolution, My Father sees Ahangarani once again combine photography, archival video, and childhood recollections to tell another story lost to history.

The film opens with a picture of Ahangarani’s father, Jamshid, a revolutionary filmmaker turned soldier, who she describes as a true warrior. She then tells us that when she was a child, she would be glued to the television, imagining that the soldiers she saw on news reports about the Iran-Iraq War were her father. She talks about how she pictured him as a man who could blow up tanks with his eyes closed or survive the harshest blizzard. Then one day at school, after being asked to write a news bulletin about the war, she stumbled across a photograph of another man, one she didn’t recognise.

That was Davood, an aspiring actor who used to star in the independent films Ahangarani’s father directed before the Revolution. However, when she asked her mother why she’d never met this man, she was told that he had “gone to Hollywood.” There is a compelling play with past and present tense in the film, with Ahangarani first narrating her story from the point of view of a child living in a world of make-believe, then as an adult whose experience of returning to these images feels like opening successive drawers in the archives of her memory. Switching between these two vantage points draws attention to how one’s perspective of family alters from childhood to adulthood and the sadness that can emerge when revisiting old family pictures.

A quietly moving tale about the way historical events can imprint themselves on family history, Ahangarani uses the contrast between the amateur aesthetic of her family’s home movies and the professional presentation of news footage to demonstrate the push-pull relationship between personal and cultural memory. It’s through this process that we eventually learn that Davood never went to Hollywood but rather was arrested for distributing anti-revolutionary pamphlets and later executed by a firing squad. A film about how forgetting the past can be seen as a means of survival and the recollection of memories as a political act, My Father shows how recontextualising the family archive can shed light on the travesties that are often marginalised in documented versions of history.

By adopting a micro-historical perspective of the Iranian Revolution, My Father captures the cognitive dissonance of a nation caught between optimism and disillusion, but it also highlights the unreliability of the family archive when it comes to depicting the interiority of a child. However, there was a film in this year’s programme that suggested a way that we might achieve a more accurate representation of childhood. Winner of the IDFA Award for Best Short Documentary, Rita Pauls and Federico Luis Tachella’s At That Very Moment takes the unconventional approach of placing the camera in the hands of Lisandro Díaz Deschamps, a young boy the pair discovered in the mountain town of San Javier in Argentina.

At That Very Moment (Rita Pauls & Federico Luis Tachella, 2023)

In the era of the smartphone, children enter adulthood with more documented evidence of their early years than any generation before. Is this hunger to capture every moment of our children’s lives restricting their ability to write their own life stories? With that in mind, At That Very Moment feels revolutionary: it’s not quite a documentary and not quite a biography but rather a curated catalogue of life seen through the eyes of a child. A Bildungsroman for the digital age.

The film opens abruptly, without any explanation about where we are or who we’re watching, thrusting us instantly into Lisandro’s point of view as he switches on the camera and proceeds to introduce us to his family. We meet his sister Kenza, his dog Manchita, and his father, who seems reluctant to be in front rather than behind the camera. Inquisitive, playful and sad, Lisandro is a captivating guide and far more like the complicated and unpredictable children you might meet on the street than the idyllic version you’d see in conventional home movies. “I always wonder, what if I’m the only one alive and making all this up,” he tells us as he roams around his garden at night. “What if none of this exists, not even myself?”

Films that focus on the psychological and moral growth of a child often do so to allow the viewer to see the world from a new perspective. However, the process often renders the child as a symbol rather than a complex individual trying to make sense of the world. In contrast, Lisandro’s voyage of self-discovery feels more organic and spontaneous, like watching his grasp of reality develop in real time as he reacts to the world around him. “There are things about my life I don’t even know, and I will never know,” he ponders whilst riding his bike, the camera shaking in his hand as he tries to catch up with his sister. The naivete and digressive nature of his footage underscore the richness of staying close to a child’s point of view, with Lisandro’s curious eye and sympathetic spirit offering a unique perspective of the world.

From here, the film jumps to perhaps its most poignant scene, in which Lisandro grabs the camera and takes it under his bed sheets to cry. Children cry in home movies for a variety of reasons: after hurting themselves in an accident, tiredness, or sometimes just through confusion. It’s rare to see this level of vulnerability, with Lisandro clearly a young man who feels everything intensely. He’s also not afraid to discuss his emotions, candidly revealing that he recently contemplated suicide. “I was overwhelmed,” he tells us, wandering around the garden at night as his family sleeps. “I didn’t know what would happen after I die, and I really wanted to know!” Offering images that are vulnerable, complex, direct and disconcertingly close to honest, At That Very Moment shows that if we want a more realistic representation of family life, we need to think twice about who’s behind the camera.

The films discussed above illustrate how the process of recalling your family’s past can sometimes be a painful process of selective remembering and selective forgetting. While it’s true that these photos and videos may not be a reliable record of family life, these filmmakers all demonstrate that by actively shaping and contributing to the family archive, we can forge new, more meaningful connections between the past and the present, the living and the dead.

Mentioned Films

Between Delicate and Violent

by Şirin Bahar Demirel, Turkey, 2023, 15’

Artists call it “hand memory,” knowledge that isn’t stored in the brain but in the body, and is activated when you start painting, sculpting or drawing. Şirin Bahar Demirel sets out to get an understanding of it. She wonders what memories are passed on through the hands, and whether we can read the aggressive nature of a painter from their brushwork, or the desires of a textile artist from their embroidery.

Our Special Little Secret

by Anna Hanslik, France, 2023, 16’

A smiling, naked toddler is encouraged to show off how strong she is. The same child plays in a basin in the shower and later dances naked around the room to music. Filmmaker Anna Hanslik was the child in question. In this autobiographical essay, she looks back with the knowledge that she was sexually abused at that age by a family member who also appears in these images.

My Father

by Pegah Ahangarani, Iran, Czech Republic, 2023, 19’

When Iranian actress and director Pegah Ahangarani was growing up, she thought every soldier she saw on television might have been her father. During her earliest years, he fought at the front, and a portrait of Khomeini hung in a prominent place in the house. In this personal essay, Ahangarani talks about how the Iranian Revolution and the turbulent times that ensued affected her and her family.

At That Very Moment

by Rita Pauls, Federico Luis Tachella, Argentina, Germany, 2023, 12’

A boy raised in the mountains films his home surroundings. He runs and cycles while holding the camera, creating choppy, chaotic images that match the energetic life of a child. Snippets of a young life pass by, but the result is by no means superficial. The boy’s flowing thoughts produce observations that suggest a strikingly philosophical nature. He thinks deeply about life and feels everything intensely, and that is evident when he talks candidly about his doubts and fears or disappears under the covers crying.