Renouncing Meanings

Basim Magdy’s Time Paintings

Rethinking, regrouping, and remixing are at the core of Egyptian artist Basim Magdy’s artistic thrust, always looking for new logics of his textural and aural references.

In this year’s London Short Film Festival special retrospective, “How to Look For a Future That Does Not Exist: The Films of Basim Magdy”, each short is its own small and fragmented world. In it, time, memory, science, and folk tales all blend into each other, looking to reconcile with amorphous splinters of truths. Through five of the Egyptian artist’s films ranging almost a decade of work, his deeply idiosyncratic formal sensibilities and thematic preoccupations transfixed viewers with hypnotic forays into the unknown. Talking Shorts had a chance to speak with Magdy about his multidisciplinary cinematic approach and being at peace with asking questions that’ll never be answered.

Experimental film as a label tends to be associated with formally innovative and disruptive expressions that expand one’s preconceptions of moving images beyond what narrative and industrial cinema position. However, the term’s etymology often doesn’t get the attention it deserves. The “experiment” at the core implies somewhat of a shot in the dark, toying with possibilities, sensations, and impulses, and engaging them without a set outcome. Embracing the spontaneous and unpredictable is the ethos of the truly experimental, just like in the films of Egyptian filmmaker Basim Magdy.

Nevertheless, a question arises when considering the medium at hand. Is this a fruitful aspiration for perhaps the most linear of arts, one constructed from the literal sequence of 24 frames? Is the inherent correlation of images something that can be retooled to capture the spark of unpremeditated creation? From the surrealists and dadaists playing with free association in the 1920s to the structuralists seeking to alter sensory states through expressionistic patterns and rhythms, these set of questions have always been present in avant-garde cinema’s histories, every artist embarking on their pursuit from a place of playful novelty.

In the case of Magdy, everything starts from what seems like a point, counterintuitive to the experimental: certainty. “When I talk about futility, it’s about very specific things. There are things I can control and things I can’t. The things I can control, I’m happy to explore further, to try to change. But the things I cannot, I accept, but that acceptance doesn’t mean the end. We can talk about them in different ways. It’s not going to change the way whether we can control them or not. But it might change the way we see them or the way we understand them, the way we question them,” as he puts it.

The fact that there’s no hope of ever understanding things such as time and death forces the filmmaker to engage art as open exploration, ready to make contingencies part of the work. Throughout his career, his approach to time emphasises the tension with official histories in an array of expressive forms, ranging from painting and photography to film.“I like to think of [time] as cyclical, but then all these changes happen. History repeats itself, but it doesn’t repeat itself in the same exact way because the circumstances change. For me, that’s what makes it a spiral.”

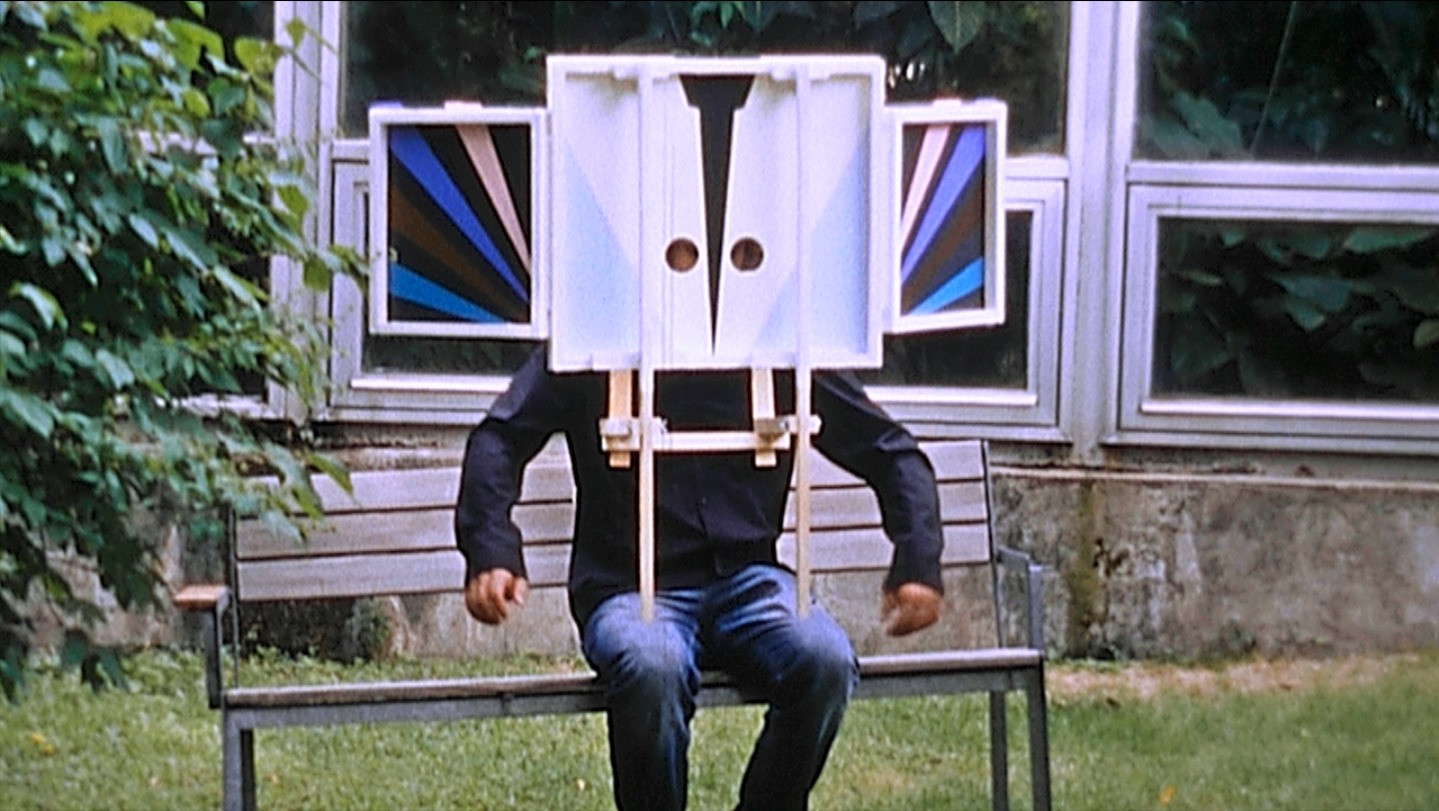

Time Laughs Back at You Like a Sunken Ship (Basim Magdy, 2012)

In each discipline, Magdy seizes its intrinsic possibilities, never translating the same logic between them, as the specificity of each of them guides his efforts to dislocate their causality. Poetry in his earlier shorts, the artisanship of his collage work, and the adventurous experimentation with developing techniques from his photography all make their way into his ever-evolving audiovisual corpus. Rethinking, regrouping, and remixing visual, textural, and aural references, no matter how obscure or how canonical, is what guides his artistic thrust at the end of the day. His oeuvre aims for new meanings and logics, like that of collage practice. Moving images, landscapes, and sounds are figments of places and times that were once recognisable, but they’re twisted and cut up so that they no longer adhere to those iterations—they’re now fragments of something bigger and new.

The tactility of Magdy’s works, all shot on film and emphasising the erratic nature of celluloid’s chemical processing and ever-degrading lifespan, reinforces the parallels with the visual arts. However, despite many experimental works originating from an expansion of modernist sculptural practice, Magdy sees his films as more akin to the painterly, “time-based paintings,” in his own words. “I pickle film in acid, and I paint on the film. Even when I structure the film, it’s very experimental. One thing I really like about painting is that when you make a painting, it doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad, or if you’re a professional painter or not. You’re creating something that no one on this planet has ever seen, regardless of its quality, and you didn’t even know what it was going to look like.”

His “acidic films”, as he calls them, seize accidents and open the doors for the unforeseen in a holistic manner. Close-up details of enthralling surface textures and flora are abstracted by how they are framed and intercut with wide compositions of ancient buildings and timeless cities, and occasionally, obtuse rituals and ceremonies experienced in medias res. They are never established geographically or culturally since that would ground them in the Earthly logic and the sociopolitical preconceptions one might have. Their ecosystem builds organically and in an emergent way, strictly in a dialectical relationship between present images and sounds and the ones that precede, succeed, and overlay them.

In A Film About The Way Things Are (2010), one of his early shorts, grain distortion and the disorienting sensory effect of double exposure are components of his symphonic storytelling, where the veneer of a futuristic scientific method, poetry, and architectural geometries, are all on equal standing when it comes to making a nebulous place and time palpable. 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World (2011) is more playful in its tone, juxtaposing authoritative, retrofuturistic voice-over with handcrafted gestures that once again manage to feel like evasive mythology.

In Magdy’s universes, there’s no hand-holding. The audience isn’t thought of as voyeuristic onlookers of worlds of wonder. They have to rewire their senses in real-time to the kaleidoscopic refractions of reality that inhabit the Egyptian artist’s imagination. Whatever might seem familiar is rapidly put on its head. The semantics of a place are purposely removed via confounding angles, soundscapes, or montages. The sequential nature of film-watching helps Magdy’s dislocation, as the natural impulse to correlate frames asserts his intended search for new contexts and meanings. “I gradually became aware that images and languages have meanings. And every choice you make has a preconceived meaning. If you track these, you will find they have colonialist or colonial roots. I became very aware of the stereotypes attached to these things,” as he positions.

In The Dent (2014), the visual plays on double exposition, text on screen, and flares of colour that the filmmaker had explored in his earlier moving image work take a step further in their role as tools for purely instinctive and sensory-focused storytelling. An erratic narrative composed of non-sequiturs creates a cryptic and vivid history for a town hit with apparently never-ending cycles of natural disasters. Time Laughs Back at You Like a Sunken Ship (2012) presents a type of contraposition where Magdy’s process of recollecting asymmetric textures and soundscapes manages to evoke a different kind of fragmented reality. In this case, the integration of botanical settings with vestiges of technology presents something akin to a solar-punk aesthetic, the closest to a tonal shift towards a wholesome oneiric landscape the “How to Look For a Future That Does Not Exist” programme ever comes to.

13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World (Basim Magdy, 2011)

The artist’s hypnotic and free-flowing sequences create a stream of consciousness drifting in and out of temporalities, geographies, languages, and even forms. However, if there is a constant amidst all these portraits of possible futures, dreamed pasts, and parallel presents, there is the lurking spectre of corroding effigies of progress. Particularly when Magdy’s audiovisual work is seen in succession, industrial carcasses become a motif, the tombstones for dreams long buried and left behind. This dialogue with Western historicity isn’t explicitly exalted at any point. As he’s expressed in public forums, his narrative interest isn’t in “fables”: “When I was much younger, before even making films, there were assumptions of context that I kept getting requests for my work to be presented in. So when I started making films, this was in the back of my mind, and a part of it was trying to create a different reality or a different understanding of reality, or maybe creating different meanings that are not attached to these preconceived ideas.”

The additive nature of his films’ ability to make settings and cosmogenies palpable is not unlike the spirality of oral history. There’s collision, repetition, and even contradiction within the same story, and because of that, it feels authentic. It’s never too pristine or calculated. It’s always about the specific way in which each film communicates. 13 Essential Rules for Understanding the World is experienced through a manifesto. Time Laughs Back at You Like a Sunken Ship is experienced as a ritual, with deliberate movements and iconographies that come into play rhythmically, creating an ambiance of perennial spirituality. The Dent flows as a visual folk tale. M.A.G.N.E.T. (2019) is ancient archaeology, field notes open to interpretation and revisited to the point where clear-cut representation is fully abstracted. “If I can express it with just words, I’d just make a book,” says Magdy, and his body of work takes that statement as its core pillar.

“I always think of the way I approach time and the past, and the present, and the future as putting them in a locked room where they play musical chairs: there are only two chairs, and they’re constantly playing. At any given point, you have two of them together, but you don’t know which two it will be. They’re all referencing each other. Time is not linear. I’m very aware of the fact that film is a linear medium, but I’m also trying, with the way I make films, to break this down and take this linearity and rearrange it.”

From Weird Fiction writers to decolonial artists, different traditions have sought to fill in the gaps in official history, renounce its rigid structures, and propose new forms of understanding. Basim Magdy takes this impulse a step further, adopting the undecipherable as his ontology, compressing and reshuffling textures, images, sounds, and sensations, and engaging the audience in a live experiment he’s also participating in, where it’s all about the primal impulse to “see what happens”.