Second Chances

Loading Love

In this Finnish sci-fi love story, Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage meets Philip K. Dick’s philosophies on the existence of android souls.

Count to three, take a deep breath, and think about all of your relationships. Let the past, present-time and imaginary future swirl: the moments you treasure and those you don’t hold on to so fiercely. One, two, three… Breathe in and wait. Is there a sudden fear you feel? Is it peacefulness that embraces you? Or, perhaps, it’s a feeling of gratitude for people who are no longer in your life. It’s not a common practice, is it? Yet, it helps to restore the bigger picture and to bring emotional balance. We all need these kinds of exercises to straddle our lost thoughts back in order. Otherwise, we might search for contentment in external sources.

Imagine a man and a woman finding such fulfilment in a romantic VR affair; this unusual situation is at the heart of Loading Love, a Finnish sci-fi love story. The director, Viktor Granö, explores a moment when a couple finds themselves in an in-between situation. Although Henrik, a synth composer, and Kira, a software engineer, have had enough of their current situation—no sexual closeness, a lack of ability to talk to each other—they don’t want to separate. What transpires is their need to find pleasure and comfort somewhere else. As a result, Kira invents a virtual (and supposedly perfect) clone of Henrik’s in VR. The replica does everything better: he composes mesmerising tunes and is also a great lover-listener, while the real Henrik is somewhat off the right track. Upon learning Kira’s secret, her husband decides to sneak into her fictional world. And, so, this finer version impresses him. A domino effect transpires as they share the same lover–Henrik is also enamoured by his artificial doppelgänger in a virtual space.

In Loading Love, Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage meets Philip K. Dick’s philosophies on the existence of android souls. Here, we follow the couple’s search for emotional substitutes in artificial intelligence. It may not be the first on-screen disintegration of a couple that has forgotten what brought them together, but it’s one of the most nuanced out there. There are subtle sequences, like one when Henrik asks Kira why she fell in love with him in the first place. “It’s hard to tell,” she answers, but then suddenly goes on, beaming, to mention the tone of his voice, his smile, and musical spontaneity. Kira’s description is well-detailed and makes it clear: even if they drift apart, the couple still remember their starting point.

There is a paradox here: love is within reach, yet the two choose to meet with Henrik’s virtual equivalent instead. They are both harmed by their day-to-day apathy, and while they long for each other, neither of them says it out loud. And, when they decide to have an affair, it’s not with someone new. This mess is a result of them running—and tripping over— towards each other, and their dalliances have an anodyne value, like a medicine to ease your everyday back pain. It’s all unnerving to watch, as we know it’s just a matter of a silly miscommunication between two people.

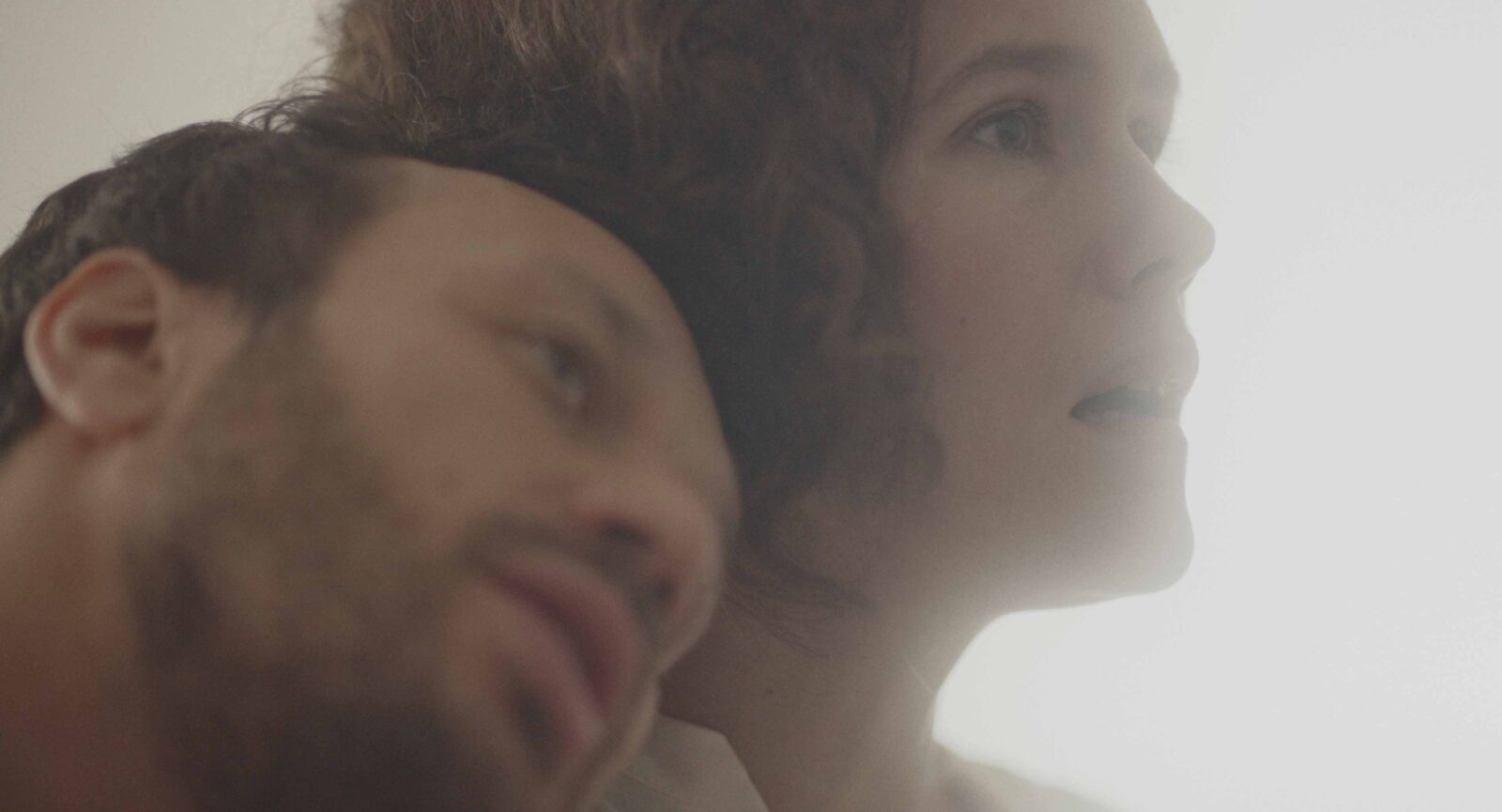

Besides, there are also visual subtleties that emphasise a growing distance. They appear ghostly in their own house, a picture imbued with emotional numbness–Henrik and Kira practically never share the same room; they often sleep separately. Lighting, too, plays a contrasting role: while reality feels bleak and desaturated, the VR radiates warmth. In Granö’s vision, VR is an idyll, an immaculate creation, the look of which easily surpasses the couple’s reality. But every paradise has a dark secret: even the most perfect likeness won’t be able to replace the real person. Granö is conscious of the fakeness that is deftly concealed in the alluring VR world. For example, when Henrik (as Kira) shares a kiss with his virtual look-alike, their intimate moment is locked in two different close-ups on each side of the kiss (he reveals each countenance without capturing the second one). Instead of opting for a single medium shot, the film hints that while VR might offer pleasure, it will never replace the synchronous intimacy of two lovers.

However, in a rather unfathomable way, a prospect for change arises. Opposite to complex and no-going-back situations, which affect many couples, in the case of Kira and Henrik, choice and hope have always been there. While Kira’s real and VR versions are played by the same actress, Jessica Grabowsky, they look different. The real Kira feels detached from her inner self: she’s no longer this energetic and always-eager-to-try-new-things kind of person, as the VR Kira is. In the real-life sequences, Grabowsky’s performance is “muted,” as if she gradually disappears. She can only be herself in VR, a magnetic and self-confident Kira. She’s the same, but unrecognisable (even her hair is different!). Henrik also wants to return to the man Kira fell in love with years ago. In their exchanges, we see a contrast between their differing personalities: between vivacity and surrender, confidence and distrust in your own skills, happiness and hopelessness. As Granö shows in Loading Love, the couple’s love is almost indomitable and has its own gravitational centre. It’s also an entrapment in which we are, evidently, our own worst enemies.

After technology has proven itself a tangible portent, in the film’s final scene, Henrik and Kira no longer use any words to discuss their relationship. Contrarily, in the very last shot we see Kira placing her hand over Henrik’s stiff palms in a medium close-up. It is the first time in Loading Love that they physically touch each other in real life. Perhaps, the ferocious and vivifying feelings are still somewhere there, waiting to be resurrected. Their intimacy only awaits to be re-discovered. We, as viewers, have seen all the signs: the couple only needs to notice them as well and, at last, stop being so blatantly passive.

How can we better understand this uncanny situation through the role of technology? Take, for example, Mark Fisher’s alarmingly close-to-the-film’s-topic deliberations. His hauntological ideas, strongly focused on the spectrum of lost futures that did not happen (but still haunt us), have led him to immensely dismal conclusions. “Haunting (…) can be construed as a failed mourning. It’s about refusing to give up the ghost or (…) the refusal of the ghost to give up on us,” 11 Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writing on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (UK: Zero Books), 22. ↩︎ he wrote. Fisher’s definition aptly fits Loading Love. In the film, a lost future haunts Henrik and Kira practically every day. This is why both of them—firstly, Kira, and then Henrik–decide even to pursue it, even if it seems unattainable. Henrik falls in love with an idealised version of himself as he longs to learn more. The ego is there, a dichotomic desire to be loved by someone but also to be “worthy” of bestowing someone with affection stripped of any fears, insecurities, and uncertainties.

Perhaps, new scenarios still await them, maybe now, more feasible than ever. As Loading Love suggests, to strive for second chances, we must come to terms with some old attritions. That’s the only way to retrieve the feelings we have once treasured the most. In the end, the spirit of emotional recovery is what’s most palpable in the film. It feels like Henrik and Kira will return to each other after the credits roll: the anticipation is there; they just don’t know when.

Similarly, if we look at the bigger picture and detach ourselves from the film’s galvanic sci-fi premise, we learn that there are much worse things than cheating, even if it is done with the (so-called) better version of your partner or even yourself. At the end of the day, the marriage in crisis, depicted in Loading Love, has everything served on a tray. Henrik and Kira just need to escape their callous lethargy, and that’s enough to make a difference.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #3—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!