Staging Tulips

Agrilogistics

Gerard Ortín Castellví mixes his anthropological interests with his creative curiosities and turns his camera towards automated greenhouses in Agrilogistics.

Filmmaker and researcher Gerard Ortín Castellví stays true to his usual interests: the food chain, agricultural production and food regimes. His film Future Foods (2021) explored the perception of food by depicting artificially fashioned food items. Before that, Castellví asked questions about the ecosystem’s imbalance caused by the disappearance of the predator in Reserve (2020). This time, he has turned his camera towards automated greenhouses growing tomatoes and flowers, where robotics control the first part of the film and magical interaction between nature and technologies occurs in its second half.

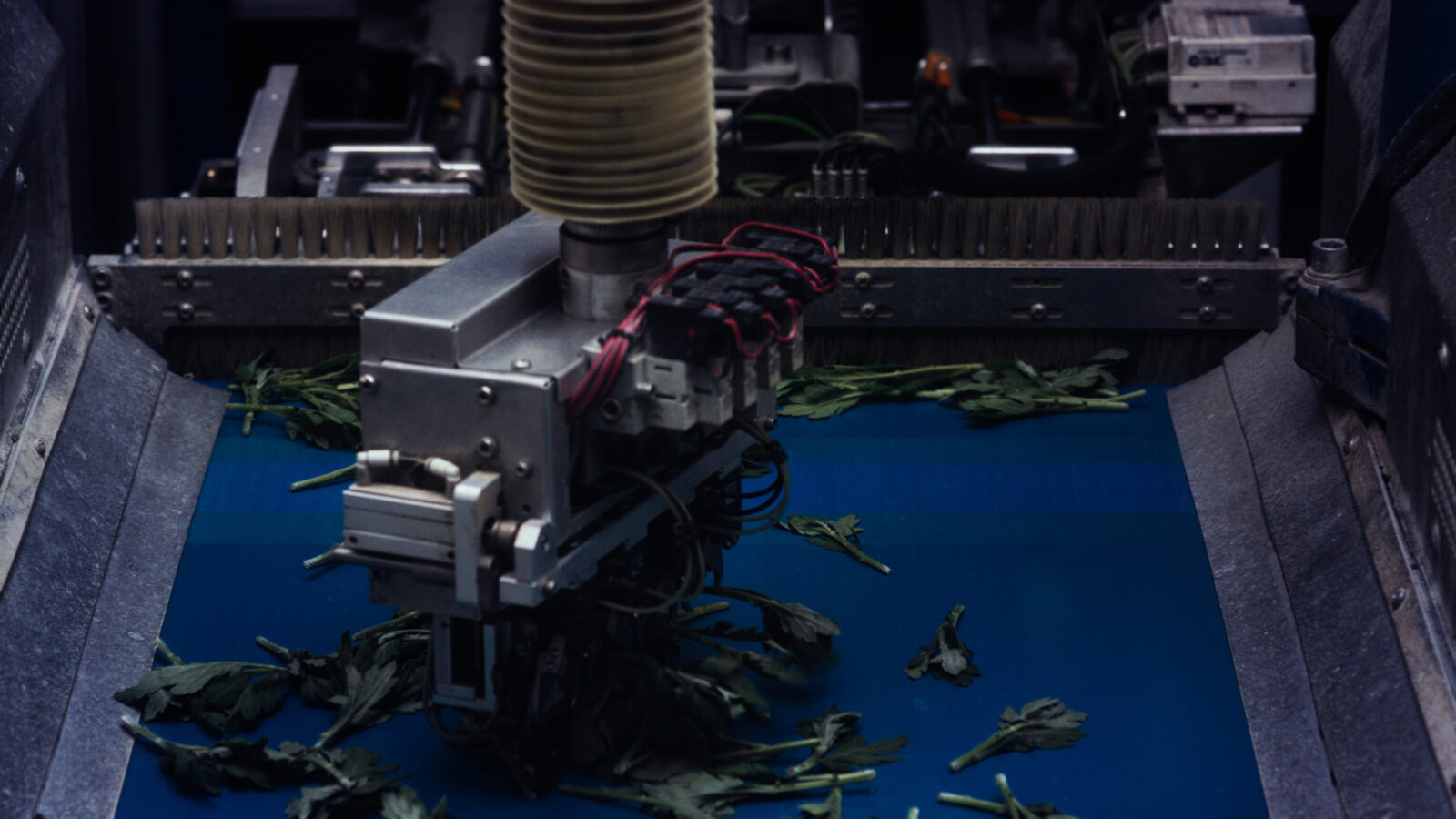

Ortín Castellví mixes his anthropological interests with his creative curiosities. The filmmaker has stated that he was interested in examining how “contemporary greenhouses [could] be understood as media” and, even more audaciously, as film sets. So what are the similarities between them? Cameras, lights and a meticulously written screenplay, just to name a few. Here, in a particular Dutch greenhouse, multiple watchful digital eyes record every angle of the tulip bulbs moving on a conveyor belt. A setting professionally lit and thoroughly monitored: the same way a film set would be.

Industrial agriculture follows a “script”, a set of premeditated, cyclic and repeated actions designed to augment the productivity and the aesthetic appeal of the chrysanthemum stems and the tomatoes. The vast difference is that a film set is more forgiving towards any deviations from the original script. The “script” written by robotics hasn’t much wiggle room left for mistakes, irregularities, or spontaneous interpretations.

Apart from drawing parallels between filmmaking and mechanised harvesting, the filmmaker also poses questions about the coexistence of contrasting concepts. Opposites collide and interact in unforeseen ways: what is natural seems artificial, and what’s normal feels fake. A case in point: the tomatoes. There they lay, perfectly shaped and shiny. The Plantalyzer’s software has ensured that they are homogenous in size, shape and colour. Though we are used to seeing these perfect vegetables on supermarket shelves all year round, the image strikes differently in Agrilogistics. I remember the tastelessness of them.

A sudden blackout splits the film into two parts. While the first part alienates the viewer with the sterility of the greenhouse, the second part captivates by means of its nocturnal secrecy. When the night falls, the greenhouse transforms itself into a oneiric flora and fauna, where nature attempts to regulate itself. Domesticised animals manage to briefly escape the farms and embrace (manmade) wilderness. This capability to shift encoded and learned perspectives is the film’s key strength. The otherwise natural act of a cow chewing grass becomes daring in this given environment. A stick insect crawling on one of the monitoring cameras feels like nature’s rebellion against technology. And a trapped bird, hitting itself against the greenhouse ceiling, throws these resistant forces back into men imposed captivity.

The film’s structure is truthful to its monotonic depiction of the production routine. In the morning after the dreamlike sequence, things go back to “normal” as perfectly shaped tulips rotate on a spinning wheel, narratively closing the circle that started with dozens of tulip bulbs on the conveyor strip. Did we have a collective dream of an alpaca and other animals barging into the greenhouse? The instantaneous throwback into reality strongly contrasts with the elusiveness of the night scene.

Similar to a film set, both acts of Agrilogistics feel deliberately staged. The camera, put exactly at the same angle as the greenhouse camera would be (on trolleys and slides), provides the viewer with the same recordings the greenhouse data systems receive–all pragmatic and factual. The dominant soundscape is composed of the machines operating. “Prayer in C” by Lilly Wood & The Prick, and Robin Schulz begin and terminate this cycle, adding a certain twist of irony to this agricultural fairy tale as only a mainstream pop song could do.

The human who orchestrated this inhuman mechanism is barely present, except for a few instances when delicate tasks must be carried out by a human hand. A strange feeling of relief (we are useful!) that doesn’t last long. These unidentified hands, carrying out routine actions, are mostly gloved, and no face is attached to them—like extras on a film set. This detachment urges the viewer to come to some uncomfortable realisations about the paradoxes of how we capitalise on nature. Agrilogistics reveals that it might still take some time to disrupt the emotionless routine of food production, but we are approaching the edge of the precipice. As the boundaries between what’s man-made and what’s natural blur, the film makes one inquire when flora and fauna will break free from their servitude to humans.

There are no comments yet, be the first!