The 24-Hour Footage Machine

Surveillance in Contemporary Shorts

The growing presence of surveillance practices has been a source for filmmakers for years. In this essay, Sarah Fensom examines how subverting the datafication of human life can be turned into political resistance.

In a recent commercial for Ring, the Amazon-owned, direct-to-consumer security technology company, “Hit the Road Jack” by Ray Charles scores a series of video clips presumably shot by Ring’s popular doorbell cameras. Quickly becoming a fixture of homes throughout the U.S. and beyond, the cameras typically capture entryways and front stoops in waist-high wides with fisheye lens distortion, and are intended to capture footage of a home’s surroundings around the clock. The ad maintains a jaunty tone, while showing a succession of attempted thefts—of packages, the family car, a potted plant. They’re all easily thwarted by the system’s two-way talk feature and automated alarms, which spout phrases like, “Hi, you are currently being recorded,” scaring burglars off. The message is clear: larceny is inevitable, but it can be just another funny video when de-escalated so seamlessly with Ring.

The ad is a bit of a departure for Ring, which tends to focus its messaging on the softer side of surveillance: tender hellos and goodbyes at the door, funny delivery personnel, animal encounters, neighbourly gestures, silly kid stuff—the panopticon decorated with Christmas lights. In the New York Times’s affiliate link arm, Wirecutter, a review of similar systems deemphasised the fear-mongering and racial profiling such gear can foment in communities, in favour of highlighting its adeptness at recording viral content. Such videos pop up on the internet and television news broadcasts all the time. Recently, irreverent Ring camera footage has even become a ruse of the long-running gag show America’s Funniest Home Videos, which has essentially functioned as a love letter to the family video camera since its debut in 1989. That these sorts of domestic memories are captured by surveillance equipment—technology intended to modify behaviour through the threat of punishment—randomly and essentially without consent rather than the purposeful gaze of a loved one, reveals our near-totalising comfort with both the surveillance state and automation.

It’s no secret to citizens in a post-Edward Snowden, post-Wikileaks world that we are being monitored constantly in nearly every facet of our lives. Yet, it’s also fitting that the surveillance system, which is now wielded by consumers and not just governments, institutions, and private companies, has reached ubiquity as an image-maker and instrument of “viral” cultural production—much like the video camera. How did we get here? Particularly in the United States in 2001, after the attacks on September 11th, the Patriot Act gave the executive branch enormous powers to monitor the population in the service of fighting terror. There was a blanket embrace of surveillance, as well as enhanced interrogation tactics—methods that Americans assumed were only used against the entities the country dubbed its enemies. But the U.S. has a long legacy of using the same tactics on people at home as abroad. As Yasha Levine attests in his book Surveillance Valley: The Secret Military History of the Internet (Hachette, 2018), the CIA was already employing the same early internet programmes to monitor both the Vietnamese and anti-war protestors during the Vietnam War in the 1960s. “They said it outright, ‘these network computer technologies […] are tools of surveillance, they’re tools of political control. They’re designed to basically pacify political movements abroad and political movements at home,’” Levine told Chris Hedges in a 2025 interview. America’s cold war with the USSR allowed for the further refinement of spy and surveillance technologies and methods, like increasingly advanced camera and facial recognition systems. Following the fall of the Soviet Union, there seemed to be a collective exhale in the West, one that Osama Bin Laden and the fall of the World Trade Center violently interrupted. The surveillance state was poised to enact a more nakedly authoritarian approach to its mission of monitoring potential enemies, one signed off on by the media and a frightened public. It seems that only with the revelations of Edward Snowden and after the growing fatigue with America’s failed, endless wars in the Middle East, the public became acutely aware of how much privacy they had truly forfeited.

Artists and filmmakers have been responding to the growing presence of surveillance practices in their work for decades. Marta Minujín and Bruce Nauman, for instance, both utilised CCTV as early as the 1960s and 1970s, as awareness of surveillance practices during the Cold War was just starting to become more publicised. In the wake of the British government spending £250 million on CCTV cameras to guard its public spaces throughout the 1990s, Jill Magid developed her 2004 video series Evidence Locker and installation Retrieval Room using the government’s cameras; the artist cut together five original narratives with the footage. Xu Bing’s debut feature Dragonfly Eyes (2017) similarly utilised China’s extensive network of surveillance cameras (the country operates sixty percent of the world’s total, having installed some 700 million in the last decade) to piece together a fiction narrative of a woman adapting to life outside of the Buddhist temple where she spent her youth. In a number of recent short films, a host of international filmmakers have similarly crafted works that focus on surveillance technology as both subject and filmmaking tool. These films effectively unravel an implicit acceptance of surveillance that both the State and companies like Ring have worked so hard to create, making viewers examine the ways unmanned cameras can manufacture human feelings.

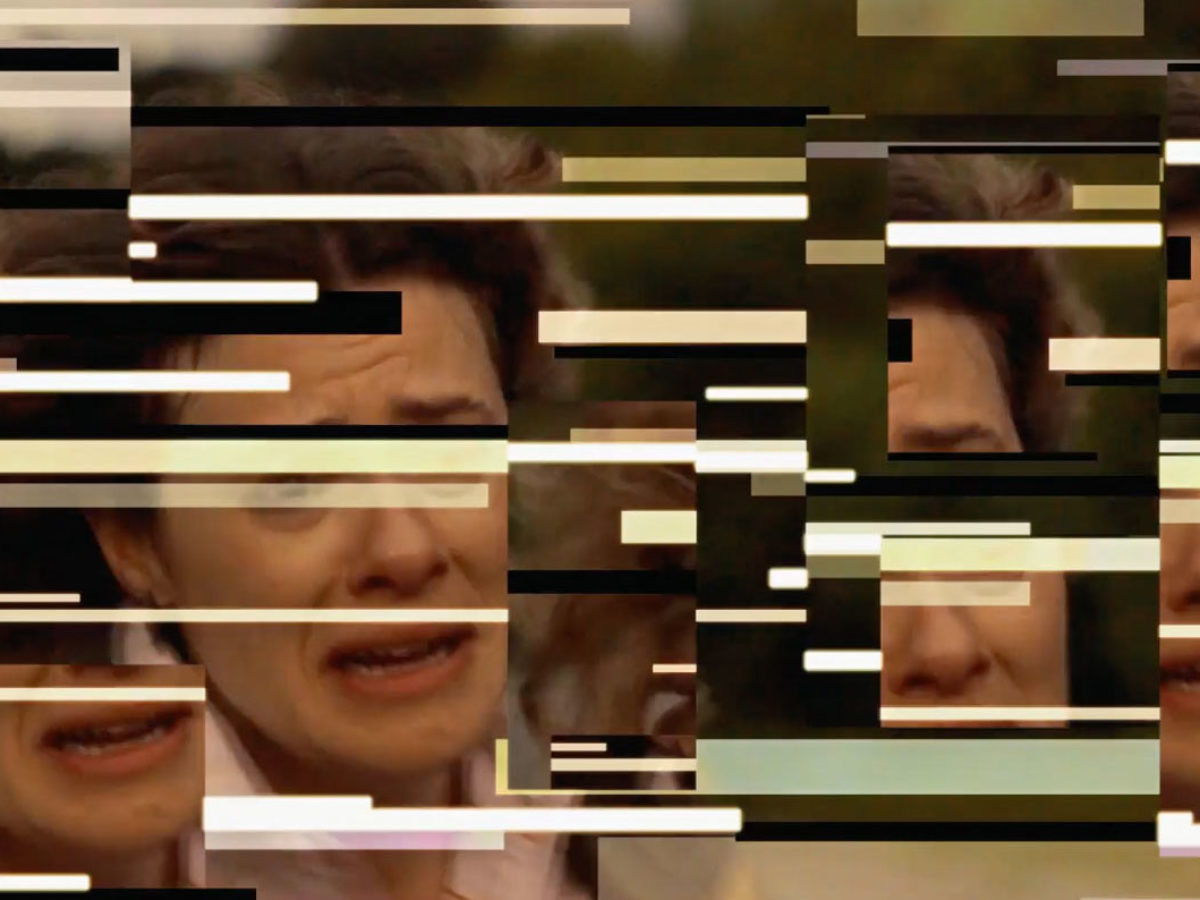

In Anna Maguire and Kyle Greenberg’s short thriller Hi! You Are Currently Being Recorded (2024), the consumer surveillance system is the explicit antagonist. It begins with Anna (Maguire) talking on the phone with a friend while staying at a house in the hills of Los Angeles. In the brief conversation, Anna makes it clear that she feels welcome in L.A. The meetings she’s had with a potential partner have gone well, and the only real drawback is that she’s smoking a little too much weed. She smokes as she heads out for an afternoon walk in the ritzy residential neighbourhood, which is bathed in sunshine and silhouetted by palm and cypress trees. Anna gets lost, and as she wanders, she begins to notice security cameras. Suddenly, they’re everywhere.

Hi! You Are Currently Being Recorded (Anna Maguire, Kyle Garrett Greenberg, 2024)

When she stops at the doorstep of someone’s home, captivated by a stained glass window she tries to photograph, the Ring alarm screams into the otherwise quiet afternoon: “Hi! You are currently being recorded.” The casual stroll quickly devolves into a panicked chase, not by another person, but rather the all-seeing, ever-present surveillance systems that guard the neighbourhood against outsiders. She rushes back to the house where she’s staying, her actions, once inside, seen from the POV of an interior surveillance camera. Knowing that she’s being so thoroughly watched gives rise to Anna’s paranoia. In turn, her paranoia makes her seem unhinged, her otherwise innocent actions turning suspicious. Because the supposed need for surveillance is rooted in fundamental mistrust, it can reframe the randomness of human behaviour through skepticism.

Hi! You Are Currently Being Recorded dramatises for the viewer the psychic encounter of the human subject with the security camera, with Anna projecting her fears, confusion, and expectations onto the unthinking machines, and thus creating the film’s conflict. We’ve been taught by films, television, and social media that if a camera is pointed at something or someone, there has to be a purpose beyond behavioural modification—we’re expecting something meaningful to happen. The brilliance of Hi! You Are Currently Being Recorded is that it creates a narrative about being perceived by a technology that ostensibly shouldn’t have any psychological or dramatic perspective, based on what the subject (Anna)—not the camera—brings to the experience. What the viewer sees are (fictional) surveillance images, but the film’s text and action live in the fact that the character can’t help but try to put the disparate, semantically empty pieces together.

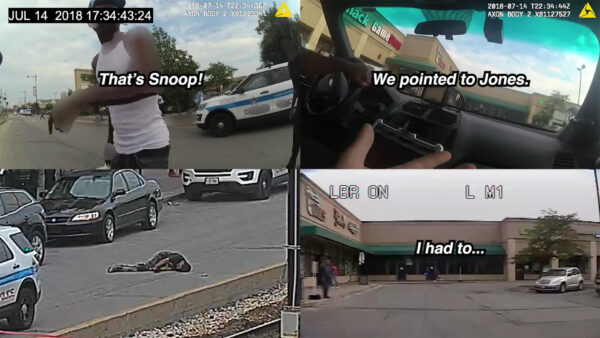

In Incident (2023), Bill Morrison quite literally pieces together footage from four sources of video—CCTV, dashboard cam, police body cams, and bystander-recorded cell phone video—to faithfully recreate the fatal shooting of a local barber, Harith “Snoop” Augustus, by Chicago police in the South Shore neighborhood of the city in July 2018. At times, Morrison uses split-screen to showcase what different cameras were capturing at the same time, providing a patchwork of vantage points, perspectives, and image formats. The effect can be disorienting, but nevertheless elucidating, especially because the murder’s circumstances remained unclear for months despite its occurrence in broad daylight and full public view.

The commercial CCTV camera, which was mounted across the street from the city block where the shooting occurred, sits high above the action and is implemented most often. It is recording the footage of a killing without any awareness, yet it seems omniscient. Because it’s silent, the film has long stretches of soundlessness, which makes the cacophonous bodycam and cell phone footage that appears later feel all the more chaotic. The CCTV doesn’t provide a very clear view of the actual moment of violence. Instead, chillingly, it captures the perfect framing for the stretch of street where Augustus’s lifeless body is left as the police quibble and try to run interference for some twenty minutes after the shooting.

The police bodycam footage, by contrast, reveals more of the interactions between Augustus and a group of four cops. They spot his concealed gun and question him; then, as he tries to give them his permit, they grab him. Shown in split screen alongside dashboard cam footage from the nearby police cruiser, Augustus wriggles free, attempts to run, and is shot a number of times by Officer Dillan Halley, before falling dead in the street. The human element of the body cams makes their footage unwieldy and emotional, especially compared to the cold removal of the CCTV. It’s also clear that on multiple occasions, the police forget that they’re wearing recording devices. They have to remind each other not to say anything on camera or to turn off their cameras, and the viewer can hear them clam up or become nervous. Their human reactions amidst surveillance devices are initially quite similar to those of civilians. But their participation in state-sanctioned violence, their own surveillance practices, and their ability to ultimately craft the narrative, means that they rarely see themselves as the true subject of observation in earnest. In light of this, Morrison’s film becomes a bold act of political resistance. The work uses the state’s tools to create a counter-narrative to the false narrative and confusion that the governing body would prefer to peddle.

Incident (Bill Morrison, 2023)

Haig Aivazian’s essay film, (2016), uses numerous examples of found footage of police violently suppressing protests to explore the power politics of light. The film begins by acknowledging the violence behind the whale oil lamp, making clear that light has always had a cost. As the film progresses, Aivazian continues to piece together social media content, videos shared via WhatsApp, and clips of didactic YouTube video essays in order to recount the history of light in public places and how it evolved in conjunction with police practices—all of this unfolding without narration, allowing the materials to speak for the filmmaker. The history of the behaviour-modifying effects of visibility, which is both the precursor and partner of contemporary surveillance tools, leads to the present, where citizens are deprived of light by the state and power companies in instances of greed and political violence, like during the Syrian Civil War. But Aivazian’s film also features examples of resistance, with the people harnessing the expressiveness of light and their own ability to use the camera to document it as a symbol of solidarity, hope, and indomitability. While those in power can twist facts, events, and realities to suit their purposes and endorse certain ideologies after the fact, the footage that we see of lights being turned off and state violence is politically important as a document. All of Your Stars uses what is essentially evidence for both a greater artistic and social statement and for the sake of political accountability.

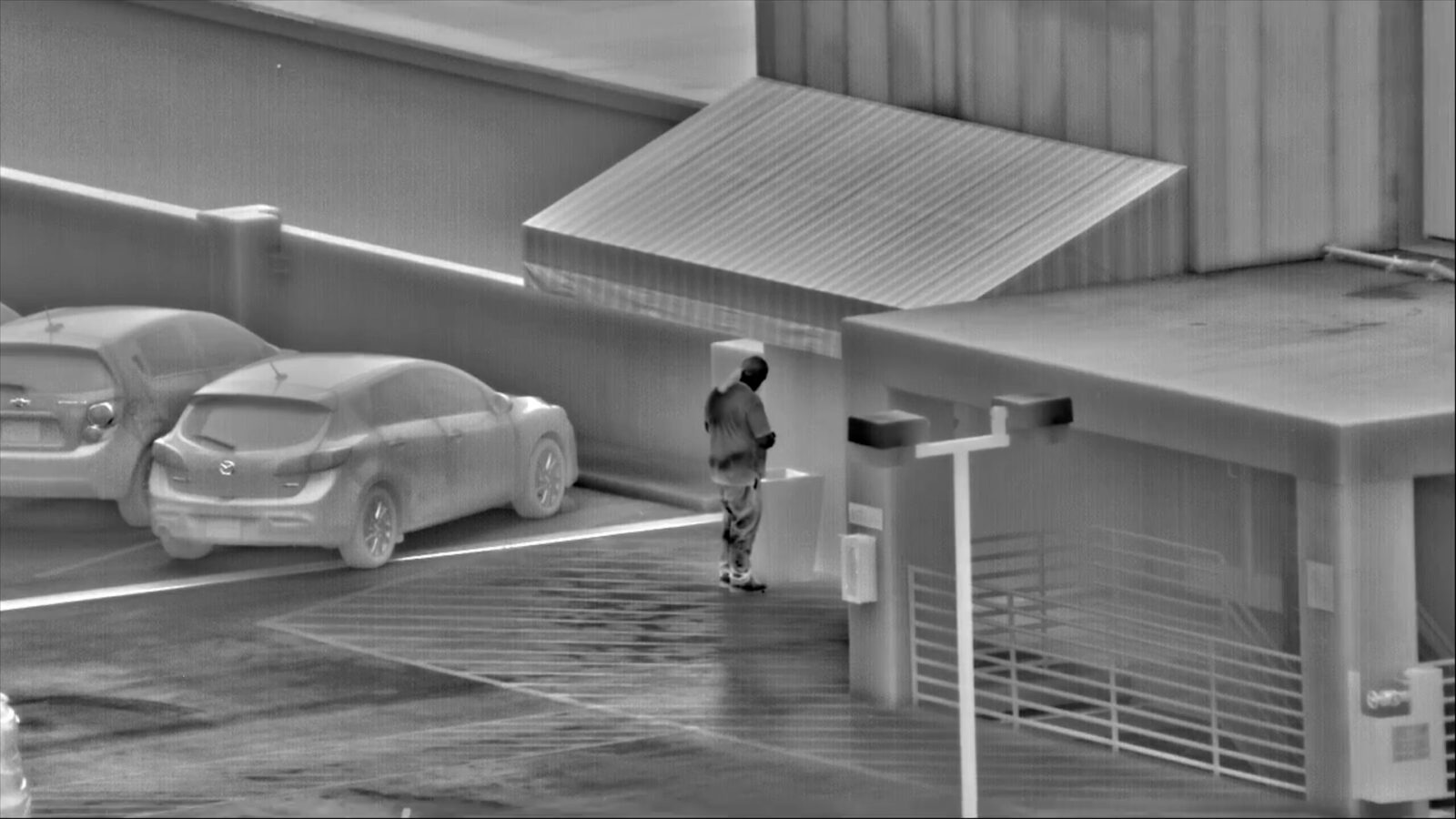

Stefan Kruse’s films utilise surveillance footage and, similarly, probe the more explicitly sinister side of the rapidly advancing technologies used by the military, police, and municipalities to watch and to collect data. Kruse’s films begin with what appears to be a documentary approach; however, they ultimately arrive somewhere that is equal parts politically and philosophically troubling. In A Lack of Clarity (2020), Kruse narrates over footage of Las Vegas. A camera seems to endlessly search the desert city—already a somewhat unreal environment made even more so by the gaze of the thermal camera—finding subjects of interest, considering them, and then moving on. The footage is from a thermal camera company’s sales pitch video. Their cameras also utilise gyroscopic stabilisation technology, which Kruse explains was pioneered in World War II and would eventually be used in steadicams that would alter the feel of Hollywood films in the 1970s and 80s.

In his 1986 book War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception, French theorist Paul Virilio outlined a macro view of the interrelation of military and cinematic technologies that seems to strongly apply to Kruse’s work, writing: “After the Second World War, it became possible to sketch out a strategy of global vision, thanks to spy-satellites, drones, and other video missiles[. ]” He goes on to write, “Thus, alongside the ‘war machine’ there has always existed an ocular (and later an optical and electro-optical) ‘watching machine’ […] From the original watch-tower through the anchored balloon to the reconnaissance aircraft and remote-sensing satellites, one and the same function has been indefinitely repeated, the eye’s function being the function of a weapon.” This is the feeling the viewer gets watching the thermal footage Kruse has appropriated for his film—that she’s looking directly through the sight of a weapon, rather than watching the footage of a movie camera. Every unassuming person seen in the smudgy thermographic imagery from the camera’s high, far-off vantage point seems already like a victim, which highlights the perverted logic of surveillance and military cameras: If there is a sight, there must be a target. What’s more, there must be an enemy, or else why is a target being scouted? This is the crux of the surveillance state and the security state’s rationale, its tautology of fear.

If this wasn’t disturbing enough, Kruse’s film articulates something more existentially troubling. As A Lack of Clarity and his most recent film A Reconnaissance (2025) play out, Kruse uses extensive narration to interrogate the meaning of the visual data he’s collecting. His voice-over, often monotone and sleepy, as if he’s been watching footage or zooming into Google maps for days, acknowledges that logical interpretation doesn’t come easily. At the end of A Reconnaissance, a film in which he tracks the movements of a highly sophisticated drone in Malta, he questions what he’s even looking at. The details don’t really add up because the images and the data aren’t very useful to the individual human eye or the human mind. What Kruse is seeing is the eye and the mind of a system, of a state, of a logic of surveillance. What begins in both films as an inquiry into the technology and uses of surveillance ends with a bigger question about his—or anyone’s—place in its logic. In Kruse’s films, his search for meaning, for his location in this matrix of machine seeing, leads to the realisation that these technologies have no semantic power outside of how they’re used. More broadly, it seems we can’t think the way that they think, and what they capture in and of itself has no meaning. But every image created by an artist, or simply a human being, for that matter, has a meaning. This is why Kruse’s films are so heavily anchored in narration, because a story has to be told.

Kruse’s films, like Morrison’s and Aivazian’s, are acts of political resistance because they speak in a human language, tell a human story that interrupts and subverts the datafication of human life, which is the easily exploited (if unchecked) language of surveillance. These artists are co-opting the unmanned surveillance camera and its footage for the sake of a greater sense of understanding—a view much larger in scope than a doorbell cam.

Mentioned Films

Incident

by

Bill Morrison,

USA,

2023,

30’

All of Your Stars Are but Dust on My Shoes

by

Haig Aivazian,

Lebanon,

2021,

17’

A Lack of Clarity

by

Stefan Kruse Jørgensen,

Denmark,

2020,

23’