The Art of Collecting

Interview with Elena Duque

Blurring the divide between cinema and magic, Elena Duque’s colourful collages are constantly testing film’s ability to invent new worlds.

Elena Duque’s is a cinema of collections, committed to exploring the many meanings that the act of gathering things might take on. Some of her shorts, like Coleccionismo (2013) or Colección privada (2020), suggest that interest in their titles, and unfurl as displays of minerals, postcards, dresses, pottery, maps, painted animals, and all other sorts of eclectic assemblages. But for Duque, collectionism “has to do with collage, and with the way that chance encounters with objects can start to form part of one’s practice”.

Sitting in the cafeteria of Vila do Conde’s Teatro Municipal, we spoke before the screening of Portales, her most recent–and, at 15 minutes, her longest–short film to date. Portales screened as part of the Experimental Competition at the 33rd Curtas Vila do Conde, and was one of Duque’s two films at the Portuguese festival; her Colección privada (2020) screened alongside works by Narcisa Hirsch and Kamal Aljafari as part of the sidebar “Radical Intimacy”. Her cinema foregrounds collage while combining different formats (Super 8, video) and techniques (animation, rotoscoping). It’s a colourful inventory of forms.

Born in Spain, when she was three, Duque moved with her family to Venezuela, her father’s native turf. She lived in many different cities—among them Valencia, Barquisimeto, and San Cristóbal—and eventually returned to Spain. “I was born in one place, raised in another, went back and forth”. Hence why collecting accrues a deeper, personal meaning: her collages offer material evidence of the places she has gone through and the people she encountered. “I’m someone with [a] very little sense of rootedness. Finding a kind of center of gravity also has to do with the things I own and carry from place to place. These are objects that often carry a meaningful weight—not always in a straightforward way. That’s also part of the game in Colección privada, where some objects are important because someone gave them to me, but others are more of a trick”.

In fact, Duque’s work thrives on tricks that blur the divide between cinema and magic. To depict and deal with the dislocation created by moving from one place to the other, she doesn’t summon nostalgia but uses cinematographic effects like the flicker. “I know flicker fries a lot of people’s brains in my films, but for me, it creates a kind of intense visual pleasure”. During a montage displaying stamps with landscapes, animals, and athletes in Colección privada, for instance, a yellow butterfly on a stamp flickers into an orange one, thus simulating the fluttering of their wings, while creating the illusion that both lepidoptera blend into one.

The same formal device is also employed in Ojitos mentirosos (2023), wherein Duque combines views of Madrid with trompe l’oeil shots of buildings, photographs, mirrors, and projections to challenge the ways we tend to perceive a place. All this is accompanied by the titular cumbia (which translates as “little lying eyes”) that sounds with different intensities to emulate the idea of flatness and depth. Thus employed, montage becomes “a way of constructing a place that doesn’t exist, a way to gather things from different places and bring them together into a single space through editing,” Duque told me. “I’m really drawn to cinema’s ability to create, unlike any other art form, moving images through frame-by-frame work, to generate things that wouldn’t otherwise exist”. By showcasing all their eclectic collections, her films challenge, question, and expand how we perceive the world, while testing cinema’s ability to invent new ones.

A key element in that pursuit is Duque’s joyful use of colour. For example, in La mar salada (2014), she streaks a book with traces of blue that look like waves, another one with pencil colours to approximate an oceanic body, and, finally, she scatters drops of water over a photograph of the sea, which then are filled with water colours. The painting’s materiality is very evident, its pictorial quality amusing. Duque’s connection to painting has genealogical roots. “My father is a painter. Since I was little, I’ve been surrounded by that”, she confessed. “To begin with, I just really like the texture of paint, the visibility of the brushstroke, and the mark left by the tool”. Her films double as chronicles of their own creation, and the words belie her interest in documenting the material process and inspirations that bring them to life. “As for colour,” she went on, “it’s hard to explain. I think I tend to use primary colours and very saturated ones. It’s also about the contrast, the impact created when things clash”. But the impact is not mathematically calculated. “There’s a silly reason related to colour, which is that for a performance I [once] bought four or five big tubs of acrylic paint—primary colours—and I keep using them over and over. So again, it’s part of that idea of chance encounters, of using what you have at hand. A lot of what I do isn’t based on something carefully preplanned, but rather on what you come across”.

© La mar salada (Elena Duque, 2014)

In fact, Duque has come across several artists and filmmakers about whom she’s collected a lot of knowledge. With regards to painting, her father’s métier was just as important as the books he bought through the years: “for example, [we had] illustrated books as well as more historical ones, like The Lives of the Artists by Giorgio Vasari”. She is also “somewhat of a student of experimental animation, and I’m really interested in the work of filmmakers like Robert Breer, who is one of my favourites. Many aspects of his work attract me, like the idea of generating a discontinuous continuity, a form of animation where one element remains constant while others change”. The influence of these experimental American filmmakers’ ideas can be felt towards the end of Ojitos mentirosos, where a view of the ocean is juxtaposed with the arrival of a subway train in Madrid, blurring wildly different spaces. Another key touchstone is the British filmmaker Jodie Mack, “especially in relation to the patterns she uses. She also works with this idea of discontinuous continuity in her textile films, where she mixes different patterns that, once animated, generate a sequence of motion, even though each frame is completely distinct”.

Duque’s passion for studying the work of others manifests itself not only across her oeuvre, but also in her job as film curator. She has been working as a programmer at S8 Mostra de Cinema Periférico in Coruña since 2013. For her, programming is “the opportunity to acquire knowledge and see things that naturally nourish my work, [and] to learn about other people’s. But it is also about having access to those people and realising how they do things and where those things come from”. Duque’s commitment to showing how her films come together also extends to the way she envisions curatorship. “In experimental cinema,” she believes, “the complete body of work counts more than the individual works. Think of Rose Lowder. One of her Bouquets may not be the film of the century, but the accumulation of that work and experimentation she has carried out is what’s important: each film is a small gesture, part of a larger whole. This is something you understand very well through curatorial work”.

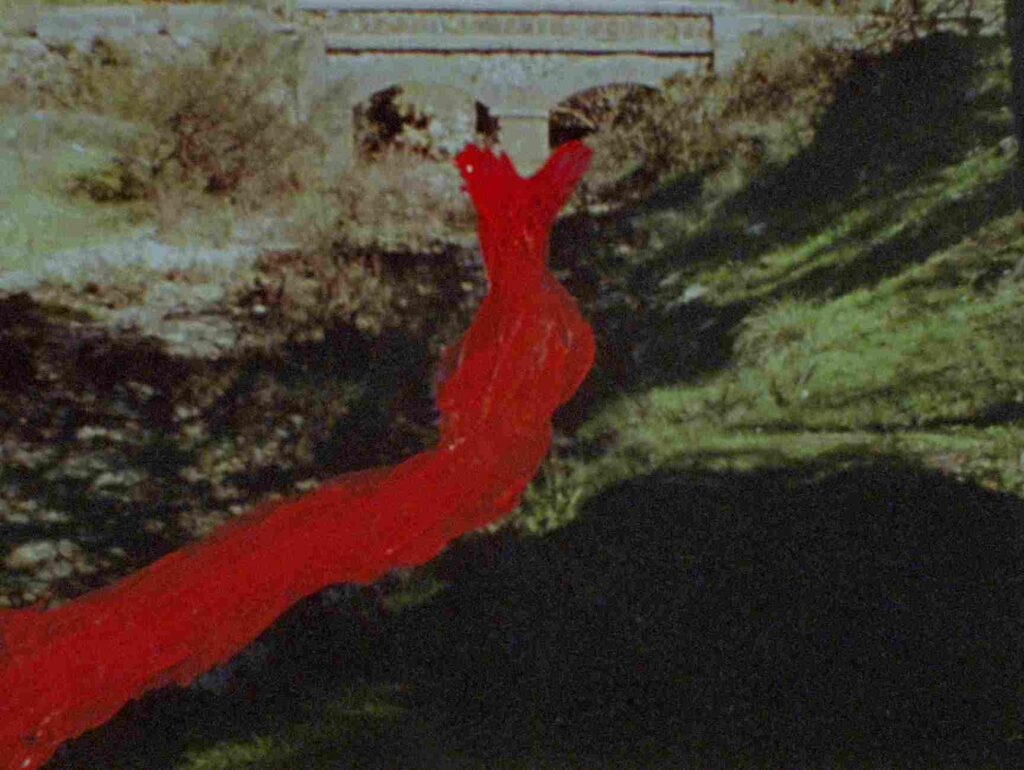

That’s one way of thinking about Duque’s cinema: a sum of fragments that coalesce into something bigger. Portales is only the most recent addition to that collection. In what for Duque feels like a feature (“it’s very long. I mean, it lasts fifteen minutes, and I already think it’s incredibly long”) within a filmography where shorts seldom surpass the ten-minute mark, Portales is a study of the Guadalete River, which rises in the Sierra de Grazalema, in southern Spain, and flows into El Puerto de Santa Maria, near Cádiz, where Duque used to live. Rather than a portrait, the short doubles as the Guadalete’s biography, which Portales captures through shots of the river flowing past the majestic trees that flank it, as well as through encyclopedia entries, diagrams, postcards, and photographs. In a beautiful moment, the river glides under the arches of a bridge. Suddenly, the water is smeared with red paint that makes it look like blood, before Duque cuts to a picture of a volcano, and the red paint becomes its lava. Finally, the image blends with that of a pyramid. River. Blood. Volcano. Pyramid. Each one substitutes the other in the blink of an eye. “The whole film is kind of an anti-climax: when you start to hear something, it suddenly cuts to something else; when you start to see a peaceful image, it shifts away. It’s all constantly disruptive—pulling you out of wherever you are.” Again, the film’s form mirrors “the sense of moving from one place to another” and finding unexpected figurative similarities along the way.

Undeniably, Elena has a fixation with aquatic bodies, “a fairly common attraction,” she admits, “that practically everyone has”. But again, making a film about a river speaks to her biography: “After all, you’re from two countries that are separated by an ocean. The river is also like a transport route from one place to another. So it was also the idea of connecting the place where my parents live with the place where I lived through the course of the river”. Water carries a certain mystery, something that cannot be fully explained so much as conjured: “it’s more what the water, the sea and everything evokes than what you actually see or know”. It’s a suggestion that may very well summarise Elena Duque’s cinema: a series of evocations that lead you to uncover things you didn’t realise you ignored, stitched together with whatever is available. “My films are very imperfect,” she noted. “But because of this, well, let’s embrace everything that goes wrong, let’s incorporate it anyway.” Here’s hoping Elena Duque’s beautifully imperfect collages will keep bringing new objects together, narrowing the gaps from one point to the other.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #7—a tandem workshop set during Curtas Vila do Conde and FeKK – Ljubljana Short Film Festival—and edited by workshop tutor Leonardo Goi.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.