The Birth and Death of a Film

An interview with Bill Morrison

With over fifty titles to his name, Bill Morrison’s body of work is tied together by the word ‘archive’, as all of his films interrogate already existing footage, helping audiences discover images deemed lost or decaying.

The day before our interview, Bill Morrison delivered a three-hour masterclass as part of Vilnius Short Film Festival’s Industry Days. The room was full to the brim, excitement palpable in the air; when a slight hitch with the dimming lights prompted him to suggest we keep them off while he talked on the podium, we all knew we were in service of what we saw on screen. Back then, we still didn’t know about the Oscar nomination for his latest short, Incident, which European Workshop for Film Criticism participant Jan Tracz reviewed from Vilnius last year. This year, the festival screened it again as part of the tribute “Footprints of Images: The Films of Bill Morrison”, curated by professor Natalija Arlauskaitė, film and visual studies scholar. The programme included also Footprints (1992), Just Ancient Loops (2012), Who by Water (2008), and Buried News (2021).

Morrison’s directorial credits include over 50 titles of various lengths, a lot of them shorts. But duration is not necessarily a defining factor in the work of an experimental filmmaker whose political inclinations permeate the very material of cinema: nitrate, celluloid, and the pixels of CCTV are some of the tools at his disposal. What unites the American director’s vast body of work is the word ‘archive’, as all of his films rework or interrogate already existing footage. Within the context of Morrison’s oeuvre, the ‘found’ in ‘found footage’ is of crucial significance, since he helps audiences discover films deemed lost, underseen, or simply decaying. He works closely with archivists and discarded reels and tells their stories anew. “I’m interested in not just the moment of a film’s birth, but also the moment of its death, if there is one,” he says at one point during our talk, alluding to the cyclical nature of cinema, filmmaking, and life alike.

As I meet him the following day at the museum café, I begin by asking him about the structure of his masterclass: his work divided into three sections, based on whether the source material was a single film or multiple films in the same archive. Morrison showed films—some in part, others in full—but he gave us a story of the context: what archive, where he found it (or the archive found him), and how he worked with the footage. Surprisingly, there was no pedagogical nor didactic approach to his partition or his stories, yet when I, in preparation for our talk, dived into Morrison’s rich body of work, all I had were the films themselves.

I jokingly suggest he was drawing a sort of a map of his work. He laughs. “Yeah, almost like a map that can show you there’s different ways of treating footage, that anything can be a film, you know? If your idea is large, you’re probably taking more disparate pieces from different sources and trying to support it, maybe, or mosaic,” he says. There are so many paths to take when exploring Bill Morrison’s work, so I decide we should start at the root.

During the masterclass, you mentioned that every new project begins with an image that captivates you. Has your definition of a ‘captivating image’ changed over the course of the thirty years you’ve been working?

I guess it has! Coming from painting, you could say that I have a somewhat romantic aesthetic. [laughs] There’s a great deal of beauty in the images I choose. When I arrived in New York, the East Village gallery scene was dominated by a sort of punk aesthetic; it was cool to make stuff that was ugly, you know? Personally, I’ve always resisted the idea that visual art should not be interesting to look at: there needs to be a visually compelling thing about it, whether or not you want to call it ‘beauty’.

What about your short, Incident, which serves as testimony to a police crime and its cover-up?

In the case of Incident, it wasn’t that kind of visually compelling thing that started it, but there were visually exciting moments that held my interest and made it like a jigsaw puzzle to solve—like the seagull, or the waiting car too. And there were narrative moments that happened almost under people’s breath but were very telling, such as the exchange between the cop who shot Augustus and his partner, where she had to assure him there was indeed a gun before he could carry on with the narrative that Augustus pointed a gun at him. A huge narrative leap takes place within a second or two: that was compelling to me. These were important moments around which I knew I could build a film.

Prompted by Incident, but also by your feature Dawson City, Frozen Time [from the same archive as Buried News] as well as your shorts, I keep thinking about death and decay, finality and loss—these are irreversible things. But watching your films testifies to the opposite: loss can be reversed. I find a lot of hope and optimism there. Making a film that can be shown again and again is perhaps a way to make the finite infinite despite working with materials that are finite and in poor condition.

Oftentimes, my final image relates to my first image with the idea that it could be played again, that this ghost is an iteration of the film. At the same time, it changes because the context changes. Each screen is different, we’re older—maybe it will change history, or it will decay as well. Now, with digital technology, the film doesn’t really have to end. It used to be the case that you had to cut a negative, and that was it, and now you can kind of slip in new things and make a new DCP and change things. No final cut is really final.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but do all your films exist in the digital DCP format?

Well, now they do, yeah. The last one I finished on 35mm was The High Water Trilogy in 2006. It was fun [to do] because we found an original nitrate negative and made it a ‘dupe negative’ of the film. So, in other words, we were very close to the gap in the original.

Just Ancient Loops (Bill Morrison, 2012)

Before you could use scanners, how tactile was the process of working with archival footage?

When I started working, we didn’t have scan material, so the process was very tactile. Tactility was sort of what brought me in [to film] from painting. My first film professor, Robert Breer, was an animation genius who also came out of painting and sculpture and made these films that were all drawn or painted on 4 x 7 index cards. Each frame was a work of art, quite literally a painting. He’d say that all filmmaking is a series of paintings or drawings, and what interested me about that idea is how it corresponded to our own memory.

You don’t mean that in the way that, say, Alain Resnais or Chris Marker meant it, though?

If you aren’t aware that different frames are making up every second [of a film], then you just buy an illusion. But if somehow you’re made aware that you are, in fact, witnessing this persistence of vision, then [film] means something completely different. You’re still aware of the illusion, but you’re also self-reflexively aware of the vehicle transporting it. And I think that’s where it becomes more of an analogy to our own experience. Sure, we can all go to the movies and dive into the story on screen with hopefully as few distractions as possible, and we believe the lie. But I think there’s a different type of cinema where it’s also about you sitting in the cinema, aware of your existence. Somehow, that perception on the tactile level is what sends you back into your seat and into your head.

Did you try making animation yourself?

My first experiments in art school were attempts at animation,which, of course, was very difficult. I spent way too long on each frame, which didn’t help anything. [laughs] So it was all too slow, and I was too lazy. But what came out of those experiments was that I found different ways of somehow affecting each frame of film without having to draw it by myself. I had this idea that if I shot negative film and then printed photographs from each negative frame or every fifth negative frame and then developed them as prints, I could reanimate them with my hand having gotten in the way. But that was very labour intensive, something for a 20-year-old man to try out… Also, I made sure that I did a very bad job of processing each print; I would have a paintbrush full of developer and splash it on top of a frame and then maybe partially fix it. As a result, I got these very modelled developed prints which, when you reanimated them, you’d be aware of the continuity of the photographic image, but also of all these different layers of materiality that comprise it.

It sounds like your approach has remained unchanged, actually.

Ha! Well, eventually, I learned of the Paper Print Collection at the US Library of Congress [since the copyright law did not cover motion pictures until 1912, early film producers who desired protection for their work sent paper contact prints of their motion pictures there]. There this had been done industrially, and tons of paper rolls had become film material. I was surprised to see this ephemeral material as a necessary step in archiving or at least in copyright law. This already incorporates this idea of tactility that I’m interested in, but it also has other social implications.

The development of motion picture copyright law is a necessary extension of the development of cinema. But it also brings to light how things are stored: what does it mean for something to age? If you consider these paper prints in relation to the early films they were a copy of, you can compare them to fossils and their lively originals, even though the latter were ephemeral and died out. But these [the paper prints] are footprints, like fossils that are left on paper. This discovery brought together ideas I already had in my mind; I wanted to see where my formal interest could lead me to tell a story.

Is this any different from how you work today?

I am still attracted to a good collection; my favourite thing is a collection that I know no one has seen, and I’m the one unearthing it to then tell its story. That’s what I look for. It is still a kind of detective work, but also gold-digging: why was this film buried? How was it lost? That’s an interesting story to me.

Your films are, in a way, found footage reincarnated. How important is the origin of any given footage? Does it determine the way you want to approach it at all?

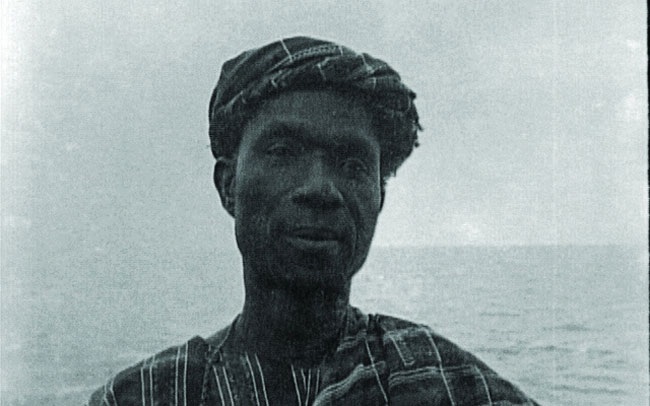

Sometimes it can be very important since it contains the story. Take, for example, the Paper Print Collection: the story of where it came from predates whatever I would find either way. [With my work on this archive,] I knew there was a great story there, so I hoped there would be enough material to tell it using clips and as little language as possible. Another example: I made a film called The Village Detective [with the footage of a Soviet 1969 film found in an Icelandic fisherman’s net] about these lost film reels that were found at the bottom of the ocean. That discovery sent me searching for not just that particular film but also its maker and the actor who appeared, as well as his relationship with Soviet cinema as a whole.

In the latter case, I was expanding the framework, as I didn’t know enough about how this actual print ended up there, but I decided to explore the context, leading me to some geopolitical findings. I’m always open to those stories. At that party last night, someone told me about a [film] collection that had been buried somewhere in France and now life is growing out of it; I thought that could be an interesting lead to follow!

Who by Water (Bill Morrison, 2007)

There is this perception of archives as precious, but in a fragile kind of way. Lots of the footage you’ve used is in various stages of decay, which is another kind of fragility. Do you think about the material in such terms at all?

It’s a necessary condition. Many people think my work is wistful or about how we’re losing our film heritage, but it’s not really about that, it’s more pragmatic: “This is the way things are.” We’re all going to decay, so why should films be any different? But there are different ways for an archive to be fragile. No archive needs to exist if people don’t engage with it. At the beginning of The Film Of Her, there’s a sign saying that if a tree falls in the wood and nobody hears it, it doesn’t exist, and I think that is not only true for the ephemeral nitrate films that I find that nobody else can see. Even the nitrate vault manager can throw them away without looking at what they contain. So yes, there are images I’ve rescued from the void.

But there’s also the fragility of this ubiquitous and vast surveillance archive, right? [Surveillance cameras] could have theoretically recorded my entire walk from the hotel to here; it’s stored somewhere, somehow, and could be reconstructed. That’s only necessary if something happened within this walk and that something was allowed to be researched and not deleted—there’s also a whole concept of an archive that only exists for a purpose. In some ways, it is a theoretical archive because it’s just too vast to search.

What about the care for the archive, and the word gives it away: what is the role of curation and curators in all of this?

It begs the question: who makes the call? Who chooses which films should survive and have a place on the shelf and which should be dispensed with? There’s a limited amount of storage space. In the case of the police archive [from Incident], they are the curators, right? They can determine which things are uploaded or what the grounds for deleting them are.

So it becomes a question of access rather than care.

Yes, absolutely. But access also requires curation. You need somebody to tell you, “You should look at file 345.” For now, at least. Maybe we could find ways for AI to scan all these files for us, and to find metadata that can then be examined by human eyes. But otherwise, it’s lost in plain sight, because there are so many images right now. I think that’s the real difference between the physical media and the digital: there’s a limited number of the former, and they’re dwindling. But with the digital image, it’s just exponentially growing.

Well, Incident, is a perfect example—legislation-wise and exhibition-wise—that is raising awareness of the fact that access can be taken away at any point.

As the law stands now—and we’re hoping to bring attention to it as this film gains more notoriety—Incident wouldn’t exist. Because they would have said, “Well, the officers were talking to each other, and we’re going to delete this file because it’s therefore not admissible evidence.” – like an Alice-in-Wonderland interpretation of the law. Rather than reprimand officers for talking about it, they’d be taking away the recording of them talking about the crime. It’s completely Lewis Carroll! In terms of that, the ever-growing endless ocean of images, especially surveillance images, can be used against, not in favour of, or to help people.

How do you feel, as an artist, about this vast, super-surveillance-late-capitalism state of our messed-up world? How do you see the status of these kinds of images now?

For once, we still could be in a very innocent period where we even believe these images are true… Five years from now, perhaps it would be the case that you produce such an image, and people say, “Oh, that’s AI.” Everything can be a deepfake or AI. Unless you have phone or surveillance footage, it’s very hard to prove anything. But now we’re heading towards a world where none of that ‘proof’ would mean anything because you could create yourself. Then, I guess I’m going to have to interrogate what the role of a maker is again. I try to find new projects and just follow what interests me and let other people decide what my role as a maker is. From the work I’ve been making over those three decades or whatever, you can probably connect the dots and make generalisations about my concerns. But the fact is that each [film] came from an interrogation of a piece of footage, or a collection.

Reproduction is very much baked into cinema as it is in photography. The kind of old images we’re talking about can be an antidote to loss when screened again, but they, too, have to exist in the same ocean of new visual media. Do you see any tension there?

My films are essentially snapshots of a time; they allude to an ephemerality, a fluidity, and an evolution or de-evolution, but they are, at the end of the day, what those [original] images look like when scanned. The images themselves have continued to decay. We could check back on them, I guess, but they’ll always carry a timestamp of the moment they were photographed or scanned. We’re talking about dealing with ephemerality and ongoing life, but I still think of them as ghosts. They’re ghosts of ghosts, maybe, or ghosts of a corpse. [laughs] At the same time, they are subject to change as well and could be re-represented as something else.

Especially in the remix culture of our time, video essays…

Decasia, for instance, played in many nightclubs without my knowledge. This is what I’m told, having not been to that many nightclubs myself…

I wouldn’t bring in Andre Bazin for nothing, but this conversation makes me consider how we can’t pin cinema down: is it always changing, or do we keep returning to the same understanding people had one hundred years ago?

I never approached it from the theoretical [side]. I always approached [filmmaking] from the material, from the actual examples, and then I let other people say, “Oh, it’s like Andre Bazin!”

But what about the nature of cinema as a medium? With the risk of sounding abstract, is the question of cinema’s essence important to you as a maker?

It’s not an abstract question, and it’s been at the core of a lot of my work! But it does come from a place where you take cinema as a model for consciousness. That’s what it’s always been in some way, someone to say: “Okay, let’s slow down [the images of] what happens when someone sneezes and see what that’s about!” It’s about sharing the impossible or a singular vision, and quite literally dreams or consciousness. Cinema begins with the idea that this machine can put sound and vision together, and it’s the only thing that can somehow express what it means to be alive.