The Powerful Queer Space

Naïla Guiguet’s Dustin

Through an in-depth analysis of Naïla Guiguet’s titular trans character in Dustin, Jesper Rusterholz argues that the short film format actively subverts the public’s lack of understanding of the transgender community by potently deflating transphobia and discrimination by representing the ordinary.

Introduction

“Being trans is seen as a stigma—you should be ashamed of being trans, you should be ashamed of being queer […] We’re told constantly to just be quiet, to go live in the dark, to be secretive about who we are. And if we step forward, we’ll only be punished.” (Montpelier 2019)

This quote about hostility and suppression against trans people by Pose (Ryan Murphy, Brad Falchuk, Steven Canals, US 2018-21) producer Janet Mock, the first trans woman of color to sign a multimillion-dollar deal with a significant content company, concisely summarizes the issues LGBTQ+ individuals have to face daily. Within that, conversations about the rights and lives for/of trans people are far from over – which strikes a heavy chord of desire that needs to be heard, seen, and felt.

Indeed, we might live in a more diverse, driven age of transgender representation.11 This article defines representation as a) a fact or process “of standing for, or in the place of, a person, group, institution, etc., esp. with the right or authority to speak or act on behalf of these,” b) a subject (person/group) or object “which stands for or denotes another [person, object, idea or meaning] symbolically,” and c) as a depiction or portrayal “of a person or thing, typically one produced in an artistic medium” (representation, n.1). ↩︎ Recent shows such as Pose or even Queer as Folk (Stephen Dunn, US 2022), Orange is the New Black (Jenji Kohan, US 2013-19), and Euphoria (Sam Levinson, US 2019-present), and feature films like Tangerine (Sean Baker, US 2015) and A Fantastic Woman [Una mujer fantástica] (Sebastián Lelio, US 2017) have given the world nuanced, diverse transgender characters in stories that treat them with sensitivity and purpose, without falling back into sucked-dry, harmful stereotypes, such as the murderous, villainous, comedic, tragic, fashionable, or transgender personas as well as storylines with focuses only on misgendering, transition- or body-fixation (cf. Trota 2014). This tipping point is vital with the shows and movies mentioned above because it holds powerful potential for positive change. Furthermore, studies showed that it can be argued that an updated trans representation will generally influence how we view and treat transgender people in the future (cf. McLaren, Bryant & Brown 2021; Hughto et al. 2021). Assumable is that it respectfully nudges viewers’ perspectives positively because, ultimately, trans people are people with daily struggles and ordinariness and are individuals that deserve every right to be treated like anybody else and not as a spectacle to astonish or as a cinema of attraction.

Dustin Muchuvitz, trans woman and name-giving protagonist of the French short film (abbr. ShF) Dustin (FR 2020), said in an interview with Variety that “[i]n fiction, we often expose the subject in a one-sided way” (Trans.: J.R.: Rambal 2021). She goes even further and talks specifically about trans representation in film: “We don’t have trans actors playing trans roles, even though it’s a difficult experience to portray. [Some] films treat the transgender question as estranged, something unusual, by systematically focusing on cases of prostitution or over-sexuality.” (Trans.: J.R.; Rambal 2021)

This is unquestionable because the history of trans and gender non-conforming people on screen has been saturated by negative, dangerous, and dim-lit stereotypes (cf. Trota 2014; Reitz 2017). However, the ShF itself, with its discourse, has fewer tendencies to be dependent on a heteronormative, white, and cismale society since any ShF can run under the radar and act more socially critical (cf. Staiger 1985). Consequently, this type of freedom and independence has the potential to deconstruct negative representations of belittling and violating the trans community – eventually strips trans individuals of their agencies (cf. McLaren, Bryant & Brown 2021). Therefore, analyzing the ShF regarding representation of transgender people seemed logical. Furthermore, one could argue that the ShF takes the chance of actively subverting the public’s lack of understanding and acceptance of the transgender community by potently deflating transphobia and discrimination by representing the ordinary.

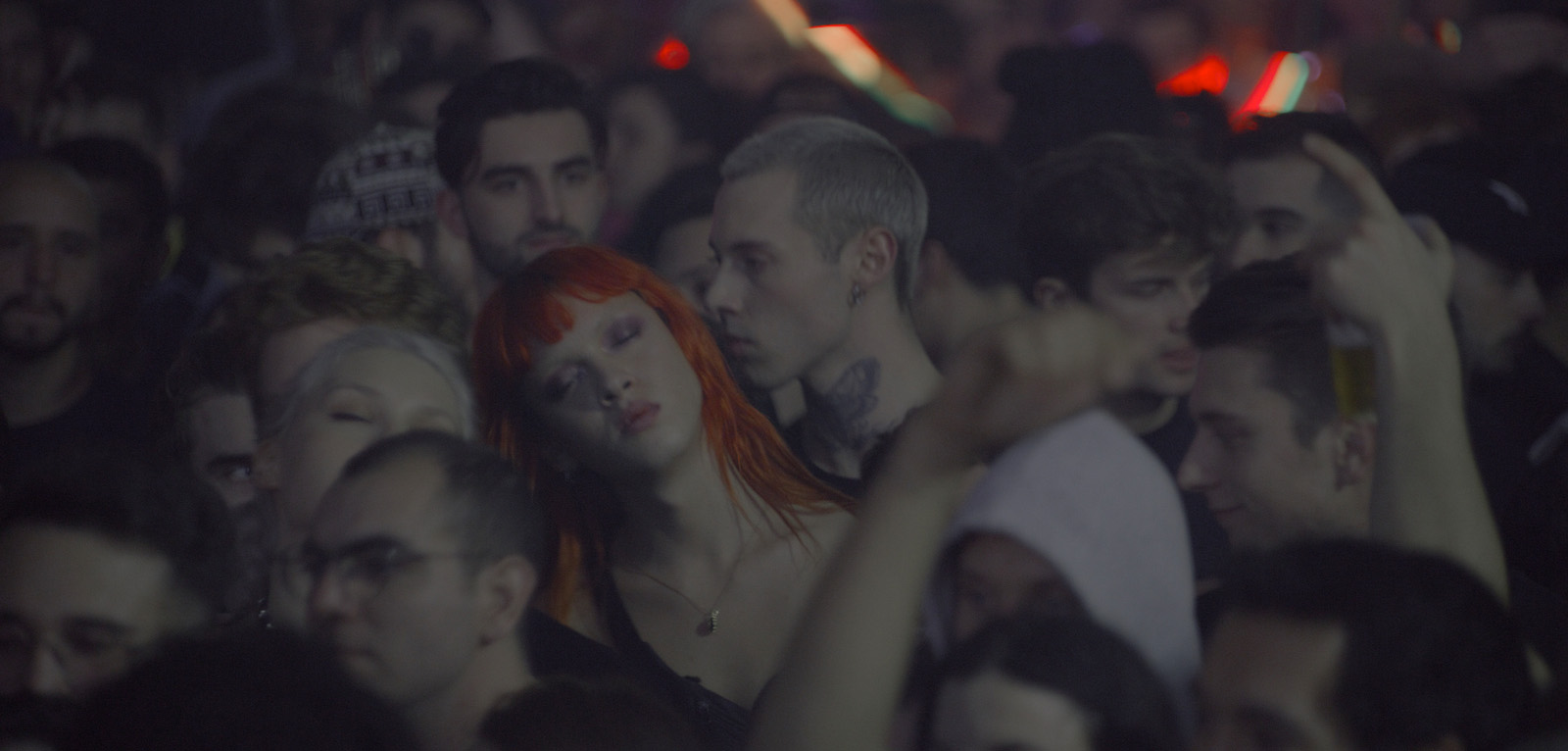

Furthermore, especially in regards to transphobia and discrimination, it can be proposed that Naïla Guiguiet’s ShF Dustin, which is about a transgender woman and her queer friends during a night out clubbing, offers itself as a rich artifact about the representation of transgender. Thus, the article demonstrates how ShFs in general, and especially Naïla Guiguet’s short film Dustin and its representation of a single transgender person’s daily life can potentially promote the liberation and normalization of transgender people by portraying non-stereotypical, non-othered and active trans women. Despite the alarming absence of contemporary academic research and analyses about advocacy, and scholars’ theses against transphobia22 “Irrational fear of, aversion to, or discrimination against transgender people” (cf. “Transphobia”) ↩︎ and neurosexism33 “The assumption that behavioral differences between males and females stem from variations in brain development rather than from socialization” (Casada & Petzel 2017) ↩︎, this article adopts theories about the ShF and representation. Section one, Theorizing Queerness and Potentializing the Short Film, will be devoted to the theories of ShFs and, eventually, connects ideas about representation in the ShF. Subsequently, section two, The Power of Dustin: Analysis of an Ordinary Representation, will use the established theory from section one and analyze Dustin’s parameters. For example its narrative and visuality, that sensitizes people by depicting the inner life and universal feelings of a (yet, fictitious) transgender individual, as well as how the dialogue addresses daily struggles subtly and politely to educate the audience without pointing any fingers. 44 This article use the methods by Bordwell & Thompson (Film Analysis), Richard Raskin (ShF Analysis), and Werner Faulstich (Sequence Protocol); although this research paper is an independent work, it also serves as an article for Talking Shorts. However, this does not mean that this text departs from the usual formal rules of an academic seminar paper. ↩︎ This is all rounded off by a short conclusion.

Editor’s note

by Laura Walde

In the spring semester of 2022, with my Ph.D. in film studies on the subject of brevity in film recently completed, I taught a seminar for Bachelor students at the Department of Film Studies of the University of Zurich. Twenty-five students signed up for this course that promised to introduce the world of short films from the perspective of its institutional linkages. Starting from the limited length of the short film, its marginalisation in film theoretical discourse, and its circulation in different institutional contexts, the seminar was dedicated to the specific formats and forms of presentation that the short film can take. It is also about the epistemic potential and implications of “brevity” as the undercutting of a norm on a cultural, social, and political level. The seminar aimed for students to become familiar with a broad corpus of historical and contemporary short films and to gain an overview of the still very limited academic research on short films.

The students were required to write seminar papers, and I contacted Talking Shorts early on to propose a collaboration for publishing those essays from the ones who were willing to write them in English and make an extra effort in preparing, writing, and revising their texts. The idea behind this collaboration is that there is hardly any opportunity to publish—and thus also read—in-depth analyses of short films in an academic context. This format—fifteen pages of text peppered with quotes from film theory and footnotes—is an unusual format for Talking Shorts, but we are excited to make some first steps in testing how longer, complex studies that go beyond a review of an individual film can be presented on a platform like this.

Free in their choice of topic, it is not surprising and indeed no coincidence to me that all three students chose to write on queer themes: 1) “The Portrayal of Queer Mental Health in Short Films”, 2) “The Powerful Queer Space in Naïla Guiguet’s ‘Dustin’” and 3) “Contrasting Double Features. On How the Combination of Contrast Programming and Double Features Can Elevate the Modern Queer Short Film Experience”. One of the significant points of discussion during the whole seminar was the political potential of short films to be disruptive, to question established codes and paradigms within the art of the films themselves, but also based on the fact that as short films, their place is in the offside of commercial and popular cinema culture.

The publication of these three essays coincides with a panel discussion on the topic of researching and writing about short films in academia at Internationale Kurzfilmtage Winterthur on November 10, 2023: The Future of Short Film: Leave the Bubble, Unleash the Shorts.