The Quiet Force of Introspective Filmmaking

On the Works of Antoinette Zwirchmayr

Austrian filmmaker Antoinette Zwirchmayr shapes her unique work around human bodies, natural environments, and their entanglements with both personal histories and collective narratives.

A mane of long, curly brown hair scatters into a frame filled with a sand-coloured stone structure. Apart from a faint breeze, the only visible movements are minuscule blemishes on the analogue film strip. The next image provides another glance at the abstracted outline of what we can now clearly recognise as a human within the same environment, though again, this person does not move. These two early shots in Austrian filmmaker Antoinette Zwirchmayr’s slow-paced Venus Delta (2016) already manifest the crux of the relationship between humanity and the world.

Though presenting themselves as collections of materiality—skin, hair, stones, leaves, and analogue filmstrips—her films are somehow hard to grasp. They oscillate between the contrast of a static camera and carefully staged and fragmented bodies, creating a visual style that is both rigorous and lyrical.

Recently, Uppsala Short Film Festival highlighted Zwirchmayr’s work with two programmes, “Inner Longings Are Very Close To Our Eyes” and “Wonderful World”. The selected films differ in various ways—from thoroughly abstract works to more essayistic documents. Nevertheless, through a unique introspective filmmaking practice, a common artistic language arises in all of them. In search of corporeal aesthetics, Zwirchmayr’s films take shape around human bodies, natural environments, and their entanglements with both personal histories and collective narratives.

Associative Images

What that means more concretely can best be illustrated by films such as Venus Delta, The Seismic Form (2020), and Oceano Mare (2021). On a formal level, these three share the representation of the human body and natural sceneries. Whether it is the black volcanic beaches in The Seismic Form, the riverbed surrounded by lush greenery in Oceano Mare, or the sandy, cliff-like rocks in Venus Delta, what stands out in all of them is the highly choreographed quality of the portrayed characters. Through precise framing and positioning, Zwirchmayr creates images reminiscent more of sculptures and installations than of otherwise freely moving, often unruly bodies. The predominant use of a static camera, which observes rather than intrudes, adds another layer of meaning to these considerations.

In contrast to other cases where this technique often reflects a filmmaking approach focused on documentation, the situation here is different. It underscores the highly staged quality of the shots, with nature itself emerging as a second agent. Often, the landscapes move more than the bodies on-screen. Is this a depiction of symbiosis or, rather, of artificiality?

Venus Delta

Notions of the hierarchically structured dichotomy of nature and culture in the Western philosophical traditions are just as much implicated in these images: Are we humans (equated here with “culture”) superior to nature? Or do we rather wrongfully place ourselves in the center of our ideas about the world?

Consider Oceano Mare, which opens with a shot of a woman standing silently on a dry riverbank. She seems to be a part of the bushes and the trees surrounding her—she is mostly still, except for her hair blowing softly in the wind. Yet, her outline is demarcated and set apart from the environment. Placed almost exactly in the middle of the frame, what is staged in the film’s opening shot is the difference, not the sameness, between the woman and nature. As the film progresses, however, the singularity of the woman is increasingly undermined. The contours of her body are blurred. The film observes soft shadows dancing indistinctly over the woman’s back and the stony ground or juxtaposes close-ups of brown hair strands with the branches of an unrooted tree.

In the context of Zwirchmayr’s ephemeral artistic language, even minuscule reiterations become meaningful. Halfway through the film, we encounter the same woman, only to see her now covered in black polka dots, introducing a change in the woman’s relationship with nature. Had the preceding images focused on establishing a likeness between the woman and her surroundings, these black dots now intensify the difference again. It is exactly on the surface of the body that these differences display. They make its outlines, skin, and curves hypervisible. The arrangement of these scenes culminates with a close-up view of a beach. Black marbles are nestled within the natural crevices of small fjords, as created by the ebb and flow of water washing over sand. Almost an allusion to the notion of “life imitates art”, nature here is depicted to have, in response, mirrored the woman’s predicament.

The opening pancarte of Oceano Mare reads: “I will save your daughter, and I will save her with the sea.” What the film shows, however, is much more than that: it depicts vulnerability, the naked body in nature, its skin touched and simultaneously touching itself, a desire to melt into each other. It represents a complex introspective relationship, visually imbued with nostalgia, one that, in its sensuality, indicates a deep yearning for a sameness that can never be achieved. We leave imprints of ourselves everywhere we go, but we also “are” everywhere we go; we become the ground on which we stand and, in turn, change it.

Several visual motifs and themes in The Seismic Form are reference points for comprehending the film. Some of them, particularly the displacement of humans into nature, bear an unmistakable resemblance to Oceano Mare. The Seismic Form develops these ideas and goes a step further, depicting the body not in but as a landscape. Buried underneath black volcanic gravel, a man’s tongue reaches out of his mouth into the air, licking it like a flame. His breathing causes the sediment to rise and fall. The narrator’s voice relates: “At the bottom, the ground never existed, only a cracked epidermis.” This quote, extracted from Jean Baudrillard’s writing, can help grasp Zwirchmayr’s films in general. Arrangements of precisely captured surfaces—both human and non-human—come together as studies of haptic intimacy.

Oceano Mare

Imbued with sensuous aesthetics, these films transport both affect and ambiguity. A latent danger of catastrophe lurks in those environments and people portrayed. In the case of The Seismic Form, the vulnerability of both natural, built, and living structures emerges through the speaker’s narration. 11 The voiceover text is extracted from Jean Baudrillard’s writing on catastrophes. ↩︎ “Nor was there ever depth,” he explains, giving the camera’s nostalgic gaze another meaning. In one aspect, the visual records act as a memento of topographies and civilisations that were inevitably destined to erode. On the other hand, the voiceover is a meta-comment on the vulnerable material that is analogue film. Neither ground nor depth exists how we imagine—ultimately, there is no permanence, finite truth, or essence. Only a cracked epidermis.

Parallel Texts

Language plays a central role in Zwirchmayr’s films. Usually conveyed as voiceovers, the film’s texts match the observant visual approach that characterises much of her work. Yet, they do not function as explanatory tools in a conventional sense but instead are poetic and abstract. In the montage that relies on visual and textual assemblages instead of linear storytelling, the text creates a layer of evocative meaning that runs parallel to, not over, the images.

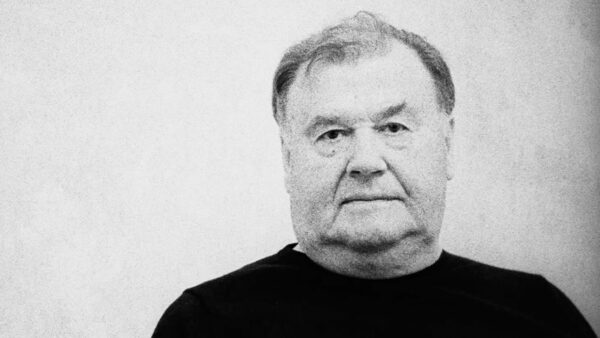

If the title of this article posited Zwirchmayr’s work as “introspective filmmaking”, this is seldom as clearly noticeable as in her 2020 film Questionnaire (Fragebogen). Here, an elderly white man faces a series of deeply personal questions ranging from fatherhood to humor and death, taken from Max Frisch’s homonymous text: “What about children makes you sad?”, “Do you feel like a dog is a property?”, “Why do dying people never cry?”

The man in the frame does not react. He sits in complete stillness, staring directly into the camera. His lack of response is highlighted visually, with strategic editing intentionally excluding his most substantial movements. Throughout the film’s eight-minute runtime, the man is seen from different angles: a frontal portrait shot is followed by subsequent cuts that show him from a 45 or 90-degree perspective, turning around his axis. The disjunction between text/sound and the film also creates a sense of temporal deferral. Asynchronous cuts of sound and image suggest that these questions were asked at a different time than when the man was being filmed, rendering them purely hypothetical, as if no answer was ever implied.

Nevertheless, the film does answer. Despite the man’s silence, the narrator continues to ask questions. “When you go to bed with another woman, do you still feel like a father?”—one of the many questions referring to ideas of manhood. Always implicated in the definition of being a man is what it means not to be a man. This silent contrast sparks gender-related concerns. Two associations especially come to mind. Firstly, there is the fact that the speaker’s voice is recognisably feminine. So what is the connotation of a woman asking a man questions, none of which he ever answers? Given this context, his silence seems like a patriarchal act of defiance. Unwilling to even acknowledge that any questions were asked, his face remains empty.

Questionnaire

Patriarchy takes many different forms, not all of which stem from sexism or misogyny. Feminists have long stressed that men, too, suffer from patriarchal structures. Most notably, the inability of (specifically older) men to communicate their emotions due to ideals of masculinity that categorise emotionality and the articulation of emotion as feminine and thus inferior. In this light, the man’s silence signifies more than simple unwillingness to respond to questions. Instead, it suggests the overarching inability of men to discuss personal or emotional topics, as posed by the film’s speaker. Due to his unwithering silence, he becomes an almost universal paternal figure, a stand-in for all the uncommunicative men we might have gotten to know in our own lives.

The specific screening conditions of a short film festival allow for even more connotations. By grouping individual shorts into programmes, the films are given an order and new contexts. Especially in retrospectives that highlight specific filmmakers’ work, this process can privilege certain associations over others. Zwirchmayr’s Questionnaire gains a heightened intimacy by being positioned between two experimental documentaries about her family history (The Pimp and his Trophies and Josef – My Father’s Criminal Record). This pairing creates a vulnerable kinship between the filmmaker (whose voice is in the film) and the unnamed, silent man in Questionnaire.

Of course, this interpretation causes friction with the notion of the universal father figure introduced above. Nevertheless, it is impossible to reduce the film to only one of these positions, for both of them are invited through the film itself and Zwirchmayr’s broader oeuvre. The same ambivalence is also inherent in Oceano Mare, where the narrative moves from favouring one interpretation to the other, making Zwirchmayr’s film(s) so captivating.

The picturesque photographic quality of her work, with its tactile sensuousness and attention to detail, is undoubtedly its most evident feature. Yet, beyond superficial aesthetics, her corporeal approach parallels layers of visual, textual, and auditive meaning so that the generated surfaces of landscape, nature, and human bodies can simultaneously coexist, creating a flexible play of associations.

As such, Zwirchmayr’s films are never dogmatic or afraid of their inherent ambiguity. Instead, they revel in it, conjuring up conflicting traces of personal histories or cultural meanings only to leave them to freely oscillate. From materialising feelings to relations between surface and depth, everything aligns to form an aesthetic that projects interiority onto the screen’s surface. A Zwirchmayr film not only draws you into the work but also into yourself.

Mentioned Films

Venus Delta

by Antoinette Zwirchmayer, Austria, 2016, 4’

The dreamlike Venus Delta offers a precisely composed and somewhat eerie miniature of jagged rock formations, a crystalline water stream, and the form of a woman suggested by smooth skin and a voluminous, crimped mane.

Oceano Mare

by Antoinette Zwirchmayer, Austria & Italy, 2020, 6’

The film approaches sensations of an ocean we don’t see. Yet there is a female body lying on a riverbed and her hair wraps around dead branches turned into stumps. They seem to have been rescued from the sea and drift towards each other like flotsam between life and death.

The Seismic Form

by Antoinette Zwirchmayer, Austria, 2020, 15’

A terrain of wet pebbles glitters and undulates. Molten lava spurts. Grooves in white, smooth rock recall the material’s own mutability. The world of The Seismic Form is one of tactile, textured surfaces, brilliantly responsive to light.

Questionnaire

by Antoinette Zwirchmayer, Austria, 2020, 8’

Is it possible to question images, and if so, what would they answer? Questionnaire pursues this question in a cinematic gaze at an older white man.