The Video Essay Finds Its Place at Film Festivals

Video essays offer various possibilities for cinematic reflection, criticism and artistic expression to intersect. Kevin B. Lee, Dana Linssen, and Eric Hynes discuss the format’s origins and its current place in the film distribution ecosystem.

In 1984, American film critic and essayist Phillip Lopate wrote that “the informal or familiar essay is a wonderfully tolerant form.” Now, 41 years later, it is perhaps that same wonderful tolerance one can ascribe to the audio-visual cousin of the written essay that aids its prominence. For a decade now, scholars and creators alike have been proposing answers to the question “What is a video essay?”, but most attempts at categorisation have proved futile. Grace Lee’s “What Isn’t a Video Essay” therefore prompts us to ask a more crucial question: “Why answer in a language other than the one in which the question was asked?” Lee’s rhetorical pondering highlights the continuity of form between cinema and the video essay in a way that does more than simply testify to the latter’s legitimacy. From this quote, it’s apparent that the task of a video essay is to partake in a dialogue, questioning, and answering, a process facilitated by the common language of editing, images, and sound.

It’s about time we see video essays as a species of their own, so we can ask the question: where is it that they dwell? Grace Lee’s work, like Kevin B. Lee’s “The Essay Film: Some Thoughts of Discontent”, is an example that can be found on Vimeo, the platform that, along with YouTube, disseminates video essays and short films globally, for free. Like short films, video essays are very rarely distributed through on-demand platforms or found on popular streaming services, but since the latter are often considered somewhat “less prestigious” when it comes to conventional festival and award nominations, they have made room for themselves. Even though Kevin B. Lee’s earlier work had been regularly published on entertainment site Fandor and today places like MUBI Notebook and Little White Lies produce sophisticated video essays in-house. Websites like Filmscalpel, Audiovisualcy, and the peer-reviewed academic journal inTransition both store and link to other video essays. Such growing online archives are based around the world, unbound by Anglophone supremacy, but all of them refer to one another as part of a symbiotic ecosystem.

Meanwhile, video essays have also become a part of another ecosystem: film festivals. Whether it’s a selection in a themed programme, a focus on a creator’s work, or—more often—part of a short film competition line-up, works like City of Poets by Sara Rajaei, Jill, Uncredited by Anthony Ing, or the films of Iranian director Maryam Tafakory screen and are awarded at festivals globally.

In 2023, Jill Uncredited was part of the short film competition at Film Fest Gent, for which I was on jury duty. For that reason, I turned to Michiel Philippaerts, curator of the festival’s short film competition, to ask whether he could outline a particularity that this video essay brought to the programme of shorts. “I didn’t think about Jill, Uncredited as a video essay, honestly,” he says. “I just approached it as a film that moved me. Of course, it is a video essay, as well. But if you ask me why it was included in that specific programme, I’d say because there were some shorts where masculinity came to the forefront, and I felt [Jill Uncredited] could be a counterpoint of this woman who was always in the background and now was showing up.” Programming decisions are not always easily articulated: “it’s more a feeling than something I can really put into a very eloquent statement,” he concludes.

Philippaerts, who also programmes features for Film Fest Gent, shares that his favourite thing about programming short films is the freedom you can enjoy when your choices are well-founded and worthy. “If it’s done well, you can programme YouTube videos, music videos, or TikToks, among more ‘standard’ shorts.” The format is not what matters, “as an audience member, if it’s a good short film, I will appreciate it, whether it’s a video essay or a narrative short film,” he adds. When asked whether he can notice a trend among submissions of video essays, he’s inclined to agree. “I think there’s more,” he says, “There’s definitely a trend, and I don’t know why, but if I had to guess, I’d say that more and more people are editing and are working with moving images. If that’s a way to think about film or to think about film history, then that’s great!”

The International Film Festival Rotterdam (IFFR) takes a distinct approach to curating video essays. IFFR’s Critics’ Choice used to be a rather standard critics-curated programme/sidebar at the festival between 1991 and 2003 (in the vein of Cannes’ Semaine de la Critique or Venice Settimana della Critica), until, after a 12-year hiatus, it was brought back, renewed. In 2015, co-curators Dana Linssen and Jan Pieter Ekker introduced what was, according to Linssen’s words in NECSUS, “not only a return but also a reinvention and a rethinking of the former [Critics’ Choice],” which incorporated video essays into its programme. In this reinvented programme, a critic’s introduction to a feature film took the form of a video essay. “[We] not only intended to give the video essay a bigger stage at an international film festival but also wanted to evaluate and reclaim the space and the role of the film critic in the festival context,” she wrote.

Goodbye Thelma (Jessica Bardsley, 2019)

When I reached out to Linssen, the first thing I wanted to ask her was whether the relaunch in 2015 came with a stake to legitimise the video essay as an art form. Today, this question seems quite outdated, but ten years ago, I suspected it was still new to the festival context. “We wanted to revamp the programme for the digital age,” she says. “The critics we’ve invited since then have always produced something that would make us [and the audience] think about cinema in a new way.” The format has been loose, as long as it fits in the timeframe of a traditional film introduction—three to ten minutes in length—and in its ten years of (returned) existence, Critics’ Choice has shown works by the ‘big names’ of video essayism, like Catherine Grant, Kevin B. Lee, and Mark Cousins, as well as supported young critics who were less established. “I believe it is a nice playground,” Linssen laughs.

Indeed, play is a crucial keyword in video essayism, as it loosens its bond from the strict academic contexts of film analysis it used to exist in exclusively. Catherine Grant, researcher, filmmaker, and co-founder of inTransition, for example, propelled the notion of “learning through doing,” as a self-taught editor who, for the longest time, cut her video essays on iMovie. Linssen cites Grant’s idea of “material thinking” as to analyse and evoke a film in and through its own means. But in summary, she adds that “no matter how playful they were, these video essays were also, in a way, very philosophical and fundamental in our thinking about the function of cinema and the function of critics in a festival.” But where do video essays live?

There is no singular answer to this question, just like there is not one global streaming or on-demand platform for audiovisual content—such a utopia has no place under the capitalist rule of media consumption. Sure, a lot of VOD platforms for shorts are alive and well—even this website temporarily hosts films during the New Critics, New Audiences campaign—but the non-curated, algorithmic universe made out of the Vimeo-YouTube-TikTok trifecta gives home to a lot of the video essay content that can be viewed for free. That many YouTube content creators are making crazy money out of our otherwise free consumption (through ads, collabs, patreon, etc.) is not surprising, but it is still more likely to find a video essay that has had international festival exposure online and free access, than it is a relatively fresh buzzy short title. The bottom line here has a lot—but not everything—to do with access. Perhaps it is the ‘remake’ quality of a video essay that makes it “less prestigious” enough to become widely accessible.

As a result, the video essays that make it to film festivals occupy a special place in the exhibition/distribution ecosystem: paradoxically, they are for the few (festival attendance is a timed privilege) and for the many (free to watch, always available), at the same time. As film scholar and producer Roberto Cavallini points out in a roundtable transcript published in Mediapolis, “distribution is the core of any real political intervention in any cultural debate, employing films as cultural weapons against mass distraction.”

Asked about whether there is a way to untangle the video essays from the films they accompany in Critics’ Choice, Linssen summarises the forms these works have taken over the years. “Some, even though you can say they are instrumental, or they are in some way in dialogue with a [particular] film, do exist outside of the festival context. It happened that filmmakers asked if they could screen the video essays when a film gets distributed, or if they could put it on a DVD. We’ve been working with the Eye Filmmuseum, where video essays were produced in relation to artworks, and were screened as part of the exhibition: those weren’t really independent works of art.”

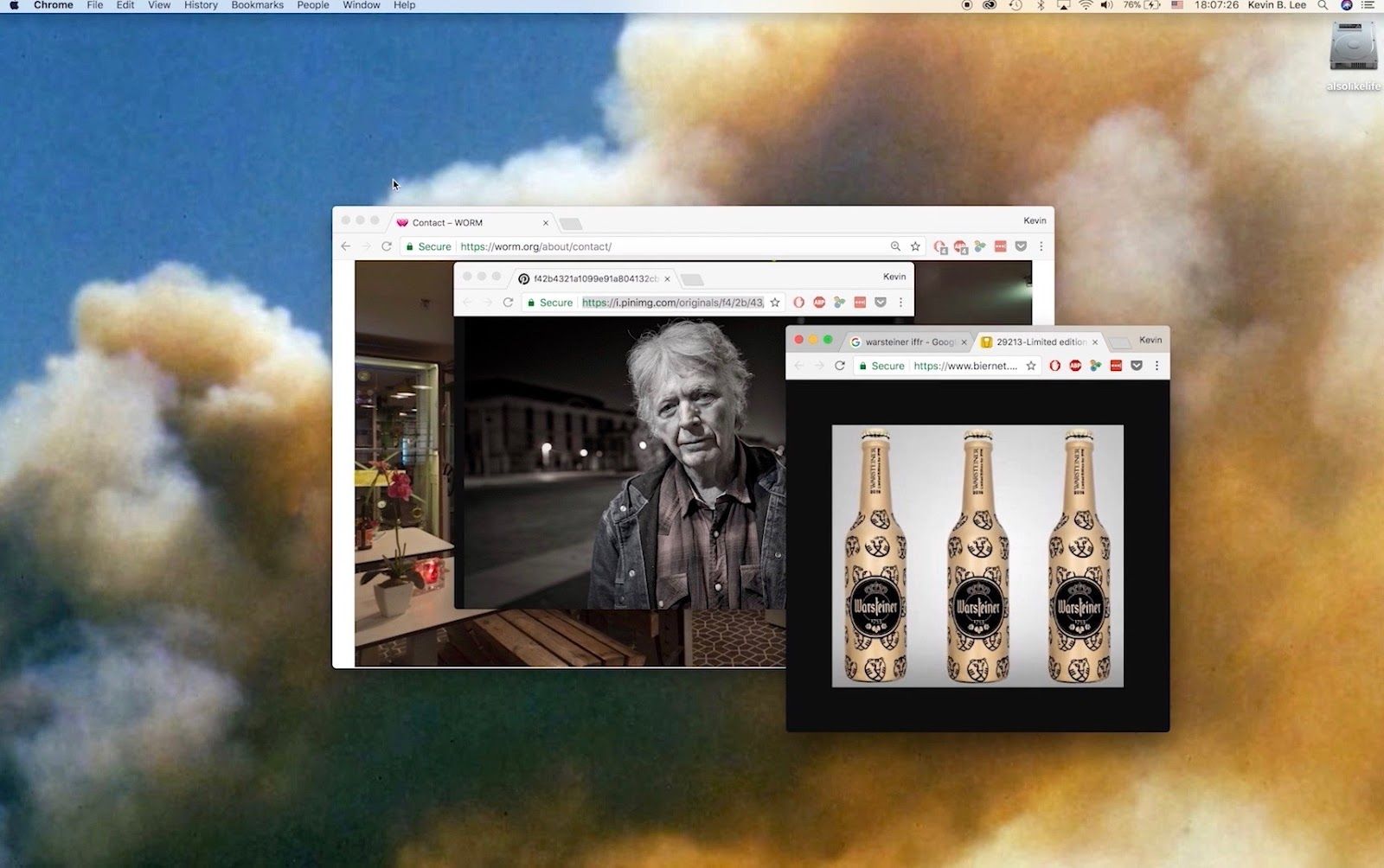

But some of the video essays have a life of their own. Let’s take, for example, Reading // Binging // Benning, by Lého Galibert-Laîné and Kevin B. Lee on James Benning’s Readers. This is termed a “speculative” video essay because it doesn’t feature any footage from the original film, and in it, Lee and Galibert-Laîné come up with many innovative ways to circumvent the unavailability of the source material. What we end up with is a short film in the desktop documentary format, where the process of collaborative research and making is continuously exposed and explored.

As a film critic and curator, Linssen is very aware of how forms and formats constantly have to reinvent themselves to express the times we live in. “Cinema changes, so criticism changes, but also the world changes,” she says. “Images at one point may get a life of their own. So what are they representing? And how do they relate to the world? For me, coming from a philosophy background, those questions were always there, but they’ve come to the foreground now.”

Video essays, in a way, lay bare the inner workings of the cinematic medium. With the ability to rewind, repeat, mix, cut, and reorder—tools that have been around since the dawn of cinema and play a crucial role in experimental filmmaking—comes the potential to engage with the cinematic mode of production by exposing the labour involved, instead of concealing it.

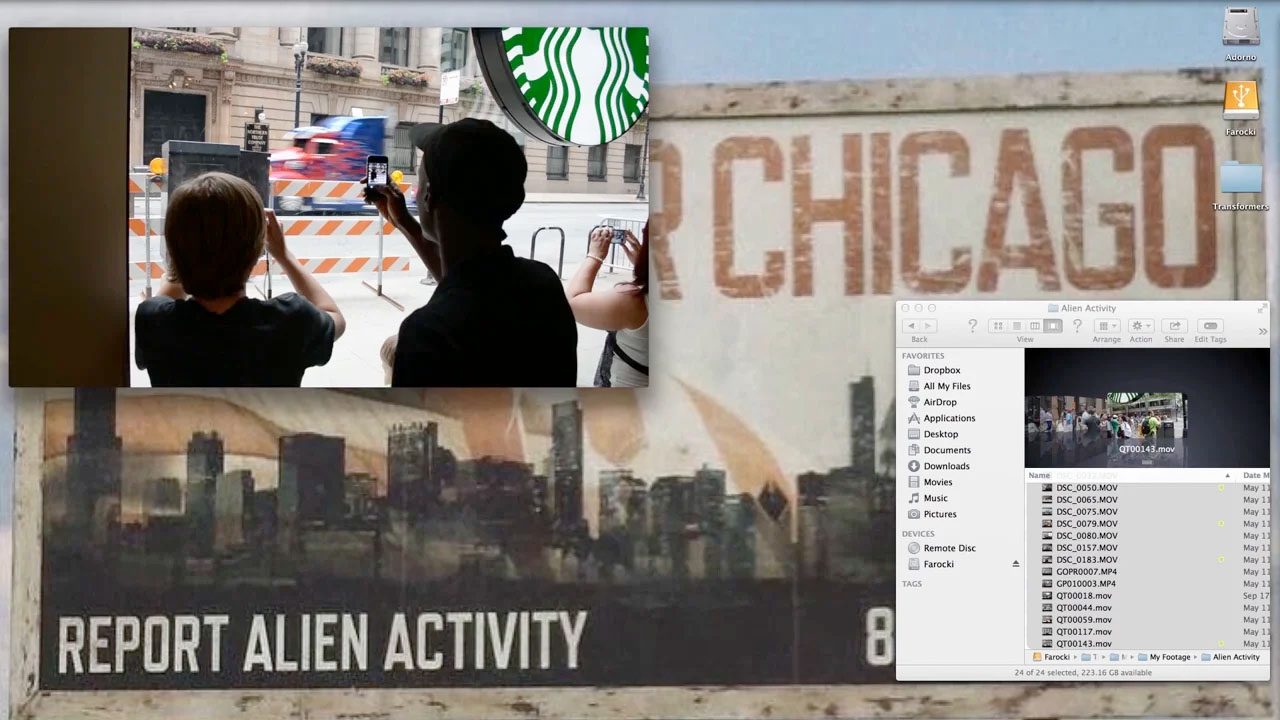

TR@N$F0RM3R$: The Premake (Kevin B. Lee, 2014)

In January 2025, the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI) in New York hosted a special showcase of video essayistic work called “Expanded Screens”. Eric Hynes, who was then heading MoMI’s film programming, doesn’t hide the fact that he has always been interested in “the transformational potential of putting moving images meant for (or first presented on) the internet, computer screens, or television into a theatrical setting.” His interest chimes with his programming work for First Look (a festival that happens in March), having shown video essays or desktop films by Chris Kennedy, Maryam Tafakory, Charlie Shackleton, Lého Galibert-Laîne, and Jessica Bardsley, to name a few. As for the reason, Hynes admits it has nothing to do with “a particular predilection or preoccupation, but more because of the strength and innovation of what’s been out there over the past decade. Microgenres matter less to me, personally, than compelling works of cinema, full stop.”

Kevin B. Lee, whose desktop documentary-video essay Transformers: The Premake was shown at several festivals, has been working on a project within the Swiss National Science Foundation for studying video essays and their ecologies. From YouTube to peer-reviewed journals like inTransition and NECSUS, to film festivals and social media, Lee is studying (and making a film out of) the different contexts where video essay practice is and how they relate to one another. I spoke to him, prompted by a showing of Maryam Tafakory’s Irani Bag at Vienna Shorts a couple of years ago, where I sensed a certain amount of distrust in the room due to the film’s video essay form, unlike other shorts in the competition. What interests Kevin and me in this case has less to do with the programming decision, but with the audience’s expectation. We’ve done so much work to move beyond the delineation between documentary and fiction; why are we still reluctant to grant ‘film status’ to video essays even when they are projected on a festival screen?

“It’s been debated for as long as I can remember,” says Lee, pointing out that while the context of consumption matters, the notion of legitimacy when it comes to video essays is still contested. “It’s funny because the thing that got me interested in video essays myself was a feature film that I consider to be like an OG video essay—Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) by Tom Anderson—a three-hour documentary, which I don’t think got legit distribution. It originates from a pedagogical and scholarly resource: Anderson’s own lectures on the topic.

It may be the case that every context subsumes the form and remakes it in some way. Lee suspects so, too. “We’d like to think that it’s easy to distinguish between, for example, explainer content or supplementary material on the one hand and art or cinema on the other,” he says. “To compartmentalise them and then classify them and say: okay, art cinema, that’s what we’re really here for! But more often than not, they’re mixed together.”

When I posed the question whether the video essay can have an originary context, Lee reminded me that cinema started to reflect upon itself critically in a way that we associate with the video essay as far back as the Lumière brothers. In Demolition of a Wall (1896), they show a wall being destroyed, while the second half of the film is the first one, played backwards. “Yes, you’re made to be self-conscious of the cinematic apparatus, but it was totally new back then. They were just exploring what was possible. That, in a way, precedes any context, let alone film festivals or the internet.” Perhaps, Lee suggests, to understand the role of video essays in a festival context, we first need to ask what film festivals are for. “Are they meant to celebrate the art of cinema in a way that you cannot find on Netflix or in the Multiplex, or YouTube for that matter? If so, that creates the idea of the film festival as a special place where you can experience audio-visual work in a way you can’t find otherwise. There would be some kind of implicit bias.”

Tafakory’s Irani Bag was commissioned by the Asian Film Archive in Singapore because they had to shut down during the COVID-19 pandemic and wanted to boost their online presence. A consultant on that project, Kevin B. Lee says it “was just meant to be like online content made by filmmakers and artists, which is also a bit of a contradiction, but of course, they went way beyond expectations,” meaning the short’s premiere at the Singapore International Film Festival and its subsequent festival run. “It was a big deal,” he adds, “because it was like [a stamp:] This is legit!” It goes to show that the video essay is a fluid form, occupying multiple functions and offering multiple possibilities for how cinematic knowledge, criticism, and artistic expression can work together.”

Irani Bag (Maryam Tafakory, 2021)

In 2021, Tafakory won IFFR’s Amodo Tiger award for Nazarbazi, a film that, according to Lee, “practices video essay in a way that a festival can embrace more openly, like art, even though there is this [essayistic] mode of analysis going on, studying and celebrating pre-existing works of art.” There is a spectrum of video essay practices, just as there is a spectrum of “curatorial agendas,” he says, and admits he finds it interesting to observe “how they overlay one over another and to see where they link up and where they don’t.”

“I think the language has changed so that the terms essay film and video essay don’t seem as binary as they used to be,” says Lee. Perhaps even the video essay might be at an advantage, he hints. “Sometimes, when you use the word film, you’re not really engaging with things happening in the digital world, which dominates our lives and culture.” The contemporariness of its name, not only its mode of creation and circulation, also makes video essays resonate with today’s cultural conditions. In this tangle of factors, Lee suspects a reason why festivals are engaging with video essays more.

“In some ways, it confronts festivals to ask themselves where they situate themselves within the contemporary cultural condition; whether they mean to uphold a certain heritage or legacy understanding of cinema and audiovisual practices,” he adds, “or are they interested in new languages, new forms, new practices, relating to the digital media, and online experiences?” The role of COVID is not to be underestimated, of course, especially since a lot of festivals had to adopt an online form instead of its traditional offline presence “in the real world”, but it’s no coincidence that Europe’s most prestigious film festival, Cannes, partnered with TikTok as an official sponsor in 2023. Needless to say, it was unsuccessful and only lasted one year. Instead of brushing it off as a cynical branding exercise, Lee sees it as something that “speaks to the festival’s frame of reference: it was remarkable to see how big a gap there can be between the cinematic and the non-cinematic.” And what is the one thing that can encompass both those worlds: the video essay. Lee admits that this possibility excites him as a maker and a thinker, that “in some ways, [the video essay] becomes a vehicle for vulgar and vernacular forms of online audio-visual language, to slowly make their way into the ‘old school’ arena of film festivals and cinema. And it’s meant to evolve, not remain static,” he concludes.

Even when we transcend the questions of taxonomy (i.e., where does the video essay sit in the grand scheme of things), the issue of genre still crops up. It’s up for debate whether, as the term ‘video essay’ expands to include more and more iterations in form, there is value in upholding the lexicon for future use. In other words, are ‘video essay’ and ‘documentary’ interchangeable? Kevin B. Lee answers that while they may not be interchangeable, they are interlinked. While the documentary is a whole realm of practice, including different kinds, like observational docs and ones closer to the ‘essay type’, “video essays, to some extent, deal with nonfiction, but they’re meant to be highly subjective, or at least allow for a greater degree of subjective expression,” he says, pointing out that is what made them significant in the first place. “It was a kind of a democratic media format, something that anybody could pick up just by using found footage, and adding their voiceover or re editing materials from existing films to kind of show their own point of view,” he adds.

While not all documentaries accommodate a similar kind of subjectivity, Lee doesn’t think we can dispense with the demarcations whatsoever. “We need words to gain some precision to what exactly we are seeing, what we want to see, and what we value. Documentary, video essay, cinema, art: these are all positions meant to map out the whole landscape of what’s possible and how different forms relate to each other. But at the same time, they’re not fixed.”

Like cinema, the video essay is not a fixed entity, and while it does admittedly evolve on its own, it still succumbs to the rules of the game. Therefore, if we rephrase the role of video essays in film festivals as a disruptor rather than a good/bad fit, perhaps we can see the hierarchical structures and logics that support the festival ecosystem anew, and learn from the transformations that are already occurring.