The World is Our Playground

Cul-de-Sac

Not a skateboard story, but a skateboard-inspired film: Cul-de-Sac urges characters and viewers to contemplate life, whatever that entails.

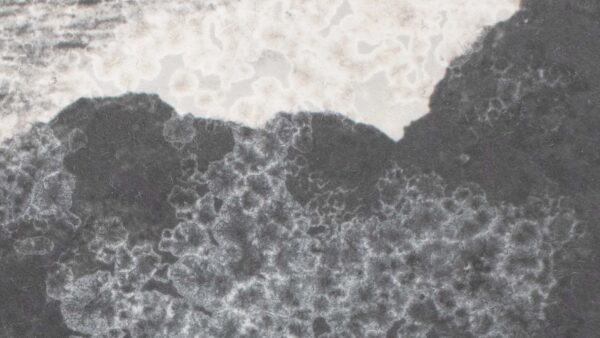

A desolate parking lot, the empty hallways of a supermarket, a quiet bowling alley, and the still setting of a shopping mall that has shut its doors down for the night are suddenly brought to life by the echoing sounds of four skateboards. Mário Macedo’s and Vanja Vascarac’s short film Cul-de-Sac sets a self-fulfilling prophecy: to prove that these four characters have reached a dead-end.

More than fifty years after Skaterdater (1966), the first fiction film about skateboarding that also won a Palm d’Or for Best Short at the Cannes Film Festival, Cul-de-Sac drifts away from the frantic rhythm, the energetic soundtracks, and the Californian landscapes that have been associated with skateboard films since then. Of course, it does not leave everything behind; the masculine presence is still very much evident, as is the quest for belonging. Yet, Cul-de-Sac is also an homage to the sport’s roots; the film embraces the idea that skateboarding emerged as a response to boredom—a convenient alternative for surfers biding their time until the higher waves would arrive again. Then again, this is one of the readings encouraged by the film’s elliptic narrative. Cul-de-Sac remains cryptic throughout its runtime, thus inviting our own hypotheses. After all, we might not be dealing with surfers, but four young men who slide along the empty hallways of a shopping mall, probably because they have nothing better to do and nowhere better to go.

Cul-de-Sac introduces its characters with considerable economy; we never learn the city they are in, any names, or relations. This prevailing silence, however, indicates they share a deeper intimacy. Either way, this almost dialogue-less script is mostly driven by a strong connection among the four characters, a sense of togetherness, even as each of them appears to be lost in their own thoughts. The only audible conversation takes place at a bowling alley, a reminiscence of an old date with a girl and a subsequent breakup for one of them. The twofold effect of this sequence can be encapsulated in the following antithesis: while the long duration of the scene would otherwise invite us to move closer to the characters, the mise-en-scène and the static camera at a distance restrict us. And however paradoxical it may seem, the scene reverberates a need for human connection of a kind that has been lost in the vast landscape of urban capitalism. Then again, it could also be a strong indicator of a generalised struggle among masculinities who have not yet learned how to embrace their vulnerability. For ages, men have been told that they are not allowed to speak about their feelings, so their words are slowly disappearing. In Cul-de-Sac, all the talking has evaporated and has now given its place to the skateboarding wheels, whose rolling sound is the main component of the film’s soundscape.

Indeed, these wheels not only serve as a means of movement for the characters but also offer the film a semblance of motion. Filip Romac, the film’s cinematographer, following a rather observational and meditative approach, opts for the camera’s stillness throughout the narrative. This elongated stillness perpetuates the idea of this inescapable dead-end as, despite the (almost) twenty-minute runtime, it feels as if we have spent the entire night with them along the hallways of this mall. It is in the film’s final seconds, when the camera frantically tries to catch up with the four skaters, that we start anticipating an escape, only to find them drawing circles back to the place where it all started.

The prevailing inaction also stands in sheer contrast with the archetypal idea of what a shopping mall is. More importantly, it reminds one that such places come into being with people’s presence. If human existence is removed from the picture, then all that is left is concrete and a couple of electrifying neon lights. In the realm of Cul-de-Sac, however, the concrete transforms into a giant playground for the four protagonists; where others see pre-determined pathways and staircases tailored to the needs of the potential visitors, the skaters’ playful imagination toys with the idea that all these have been built to serve as their palace. Burdened by the notions of industrialisation and commercialisation, they traverse locations possibly in search of an escape, only to find themselves again rolling along the kaleidoscope of an empty shopping mall. That said, Romac’s camera is not the sole observer of their late-night adventures. The film repeatedly places the focus on CCTV screens and cameras that track their movements, while also, at some point, one of the skaters pauses and makes direct “eye contact” with a security camera. Still, the four of them carry on with their activities without hesitation, despite being aware of the surveillance in place.

Ten minutes into the film, comes a peak with a scene that serves as a testament to their quest to break free from the banalities of life. The young men have intentionally set their mobile phones on fire, and they watch them burn until there is nothing left. Standing in absolute silence, their gazes at the fire are not marked by anger or frustration, but rather by indifference or even relief. Could this act be their way of expressing a wish to return to more pure and innocent times? Or is it an act of rejection towards the rolling socioeconomic and cultural shifts of recent years? As viewers, we are constantly confronted with a lingering thought that maybe, after all, this reveals an internal struggle that these skaters are faced with.

Rather than being a straightforward skateboard story, Cul-de-Sac reveals itself as a skateboard-inspired film. The skateboard here serves as a vehicle, or even the driving force, which urges both characters and viewers to contemplate life, whatever that entails. Apparently, filmmakers have been using the example of skateboarders for more than half a century to tell a rather universal story: the burden of trying to fit into a society that may not always be so welcoming. In other words, what it feels like to always come across a dead-end.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #3—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Savina Petkova.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!