Things Don’t Compute

Nicolas Gourault on Their Eyes

In Their Eyes, testimonies and screen recordings introduce the experience of online micro-workers from the Global South: their job is to teach the AI of self-driving cars to navigate the streets of the Global North. The film is now nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2026.

“Every self-driving car has its own brain,” says one of the contributors early on in French visual artist Nicolas Gourault’s most recent film Their Eyes, which highlights the hidden labour behind A.I.-controlled driverless cars. The sentence, while uttered by one of the workers feeding the technology’s understanding of traffic environments, echoes a still-pervasive misframing of A.I. technology as some form of real intelligence. Unsurprisingly, while these technologies are often paraded out as a revolutionary advancement to consumers and investors, it’s rarely the companies or the technology that suffer damage when the ‘intelligence’ does not appear to be as advanced as needed.

In March 2018, 49-year old Elaine Herzberg became the first fatality in a self-driving car accident in Phoenix, Arizona, when an Uber car did not identify her as a pedestrian in time to avoid collision. Uber’s A.I.-steered cars were in a test phase at the time, with a Vehicle Operator (VO) inside to monitor any issues and intervene when required. These safety drivers are not only low-paid but also almost entirely overlooked in the narrative around self-driving cars pushed on us by companies with little regard for the human labour they exploit and wipe out for increased profits, as evidenced by Uber’s release of footage of the VO involved in the Arizona incident. In the seconds before the collision, the safety driver did not have their eyes on the road, not a rare occurrence in this type of work due to a dangerous combination of automation bias and the fickleness of human attention spans. As a result, the VO was charged with negligent homicide, while Uber got away scot-free.

These events were the start of Gourault’s research into automated vehicles and the labour behind them, with as a first result the short film VO (2020), which directly deals with the accident. The film puts the experiences of safety drivers at its core, drawing on worker testimonies and using LiDAR technology—which enables automated vehicles to ‘see’—to create visuals, but it also provided a wealth of data and insights. “I had a lot of material around the accident,” Gourault begins. “A leaked spreadsheet showed data of what the car had seen right before the collision. It classified the person as a bag, a car, or other objects, but never as a human. Then I learned that the car didn’t have a category for pedestrians when they weren’t on a crosswalk, so someone crossing in the middle of the road could never be human. And the victim was walking her bike too, so there were a lot of complications in terms of categorisation.”

VO offered fascinating insights into the otherwise underexposed experiences of the drivers and enjoyed a wide festival run, but for Gourault, the findings from the Arizona accident opened a door to a much more expansive look behind the scenes of self-driving vehicles. “I remained very curious about that leaked spreadsheet, and it was the starting point for my research on who decides on the label, and how that is implemented in the software.”

It would lead him to make his most recent short, Their Eyes, which premiered at Berlinale in 2025 and is still impressing at festivals internationally, pocketing over a dozen awards. The film opens with segments of colourful digital images, identifying objects and living beings in Western urban traffic environments, that are rigorously labelled to feed an A.I. platform for self-driving cars. It gradually expands to a fuller view of the machine while illustrating how Big Tech relies on labour exploitation in the Global South—through testimonies from micro-workers in Kenya, the Philippines, and Venezuela. What is instantly striking is that VO and Their Eyes, while narratively connected, are visual opposites. Whereas the former is dark, oppressive and gloomy, the latter is, despite its subject, more vibrant and brighter. “Making VO immersed me in a certain mood, fatalistic and threatening,” Gourault explains. “When I started working on Their Eyes, I wanted to step away from that atmosphere. I wanted to highlight the way the workers interact, and as soon as you have a group dynamic, it gets more lively. Unconsciously, I was doing the opposite of VO, because I didn’t want to be in the same state of mind for the making of this film.”

The production of the film wasn’t a straight path. Several months into the research that built on VO, Gourault was looking for a framework to further develop and create this new work, and applied to the European Media Art Platform (EMAP), which supports art that responds to contemporary questions around the impact of new technologies in a societal context of fraying democracies and increasing polarisation. It allowed him to spend a two-month residency at Werkleitz in Halle, where the first iteration of the project, titled Unknown Label, came into being. That version was presented as a multi-channel installation, exhibited via EMAP’s venue network, but due to time constraints Gourault wasn’t entirely pleased with the result: “I’d not yet had the time to ask the workers to film their own environments, which was key to the film’s concept, so I just had digital images and nothing else.”

After the initial exhibition of Unknown Label, Gourault went back into the edit, added new material, and refined the pacing of the work, which then became Their Eyes. “A two-step process, but having that first version exhibited meant I could get some feedback and implement it. As if I was doing a test screening, but for several months,” he laughs. Although his intent was always to gradually construct the total vision of the A.I. machine, while the audience finds out about the labour exploitation involved, the piece originally had a more conceptual angle. “I wanted to use the labelled images of the machine to create an imaginary landscape that would reference the landscape of the workers. Some early audiences liked that approach because it was more theoretical and abstract.”

Hinting at the “different air pressure” between the art and cinema worlds, Gourault noticed how “people from the art world were happy to project their own ideas onto the image, but those in cinema noted that they wanted to be more embedded and needed more emotional grasp on what was happening.” Finding that balance to position the work with appeal to both worlds informed the film’s final structural approach, which ultimately moves from the A.I. machine and the workers’ experience of it, to live footage of their own nearby environments, providing a stark contrast between the rigid, dehumanising technology and the real human lives behind it.

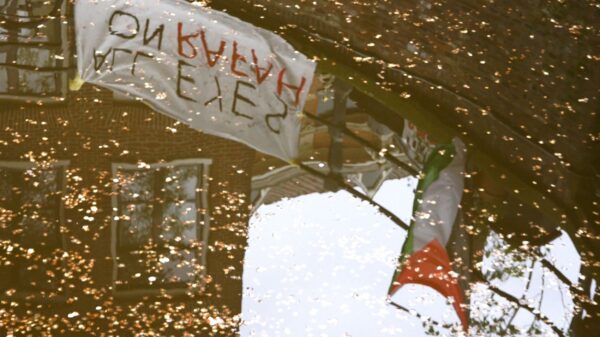

Their Eyes (Nicolas Gourault, 2025)

Crucial to the film’s development was therefore to find the right contributors to participate. Bringing together the voices of micro-workers across three different continents is vital for the film’s thesis, demonstrating a shared experience of neocolonial exploitation. “It shows the global aspect of the infrastructure, but it’s also a narrative device. Working with different people allows me to juxtapose fragments of their voices, which creates a path that I wouldn’t be able to conjure myself,” Gourault elaborates. After defining the locations that were most relevant to the project, based on high concentrations of data workers, he found contributors through working with local journalists and researchers, such as Venezuelan journalist Andrea Paola Hernandez, who had previously written on data workers in this context, and Leonard Nally Simala, a computer scientist in Kenya with first-hand experience working with the A.I. technology discussed in the film. Being able to contact people in their native tongue nurtured more initial trust in the project, and those relationships were sustained throughout. “When I would have video calls with the workers, Andrea and Leonard would always be present. Having a third person on the calls made it less frontal and overwhelming for everyone.”

Gourault particularly wanted to hear first-hand worker experiences, unguided by any particular brief or critical angle, and to construct the film from there. “If you start with someone who already has a vision about what they want to say, it can become a bit more didactic. And it would have been too specific to look for people who were already critical of the technology or who were already organising in unions,” he notes, explaining that advocacy for this kind of labour was not yet well established when he started the project. That has improved in recent years, particularly through the organising work of Data Workers’ Inquiry, a participatory research project that invites data workers globally to determine advocacy methods and lines of inquiry.

Their Eyes concludes with a shot of a busy road in Nairobi, while contributor Oliver considers the complications of introducing self-driving cars in this environment, given the more chaotic traffic. Unsaid, but on the other side of the same coin, it underpins how the West’s image of itself as better run, better regulated, has been particularly effective at priming us to adopt these technologies. After the rigid image segmentation of the machine—with one of the most revealing examples being the categorisation of a blanket-covered person as an object rather than human—seeing the disorganised road traffic in Nairobi evokes a sense of relief. “The idea behind that final shot was to reverse the point of view, from the machine to the workers, and from the Global North to the Global South,” Gourault explains his reasoning for the ending. “It creates a connection between the idea of technology and the idea of regulation and standardisation. The space [Oliver] annotates feels homogenous, but the space where he lives is much more chaotic and complex, and much more livable in a way. That was a way to talk about a sort of social fabric.”

It’s an essential factor that staunch tech and A.I. optimists often ignore in their visions of society: the human need for connections and relationships is nurtured by our relying on and trusting each other. “With these new technologies, we see a revival of the idea of a masterplan, of masterminds who must decide for the good of society. I long for the idea of self-organisation, which can seem chaotic from the outside, but can be very efficient in its own way, more emergent.”

Gourault’s preoccupation with image production and the impact of new technologies, investigating them particularly in relation to labour and collective memory, is central to much of his work. He has previously collaborated with Forensic Architecture, a multidisciplinary research group known for its inquiries into state violence and human rights violations through architectural and spatial investigation. His practice demands careful critical consideration of the tools at hand, while also remaining open to their potential when used with purpose and meaning. “I’m reluctant to use A.I., as I don’t think it fits with the ethics of my work,” Gourault says. “But I also think back to the ideological debates about CGI software when I had just started using that. They were legitimate, but sometimes got overly ideological, and it prevented people from really thinking about the possibilities.”

Gourault aims to maintain that openness and nuance in the production of his films, only utilising technologies that make sense conceptually and do not compromise integrity. In This Means More (2019), he worked with a crowd-simulation tool often used for advertising, coupled with testimonies from football supporters, to reflect on the 1989 Hillsborough Stadium disaster in Liverpool and the commercialisation of football stadiums. VO’s visuals were created with the aforementioned LiDAR technology, and in Their Eyes, he used an A.I. tool to segment the images described by the workers. “It’s not generative A.I., and it made sense for the film. There are models I would never use because I know who’s behind it, like ChatGPT, as I don’t want to feed either OpenAI or Google,” he explains, while also acknowledging the complexity of taking a binary stance on a rapidly changing tech landscape that embeds itself in almost all parts of daily life. “It’s more interesting to think critically about the use and the different actors in the field—who can you support and who should you boycott?—rather than outright rejecting them.”

Their Eyes’ strength lies in uncloaking both the technology and its corporate drivers, by showing the A.I.’s reductiveness of reality and its disregard for human life as long as it’s not harming potential profit. “Many films about A.I. present it as a god-like thing, and I didn’t want it to be that. I wanted it to work as a case study.” And Gourault does so without being didactic, instead relying on the workers’ testimonies to express the material conditions behind the artifice. “Whether it’s the supporters’ culture in This Means More or labour in Their Eyes, what is most interesting is that something is connecting people.”

Their Eyes was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2026 at Leuven International Short Film Festival by Boet Meijers, Elif Türkan Erisik, Nilay Cornaud, Oliver Dixon, Panagiota Stoltidou, and Sabrina Rose, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #8.

The European Workshop for New Curators and the New Critics & New Audiences Award are projects co-produced by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme, and in collaboration with This Is Short.