To Be or Not to Be In The Pantry?

Magid / Zafar

To be or not to be in the pantry? That is the question haunting Luis Hindman’s Magid / Zafar, in which a queer South Asian man is constantly code-switching to fit in.

In many immigrant households, survival means learning when and where you can be yourself. As bell hooks writes, queer liberation requires “a place to speak, to thrive, and to live.” For Magid, that place is the pantry—a tiny, dimly lit refuge where he can drop his guard. Magid’s identity is inseparable from the pressures of diasporic life in the United Kingdom, where conservative norms often dictate how one should behave. In the restaurant, at home, and in his community, he constantly balances the life he leads with the life he might secretly want.

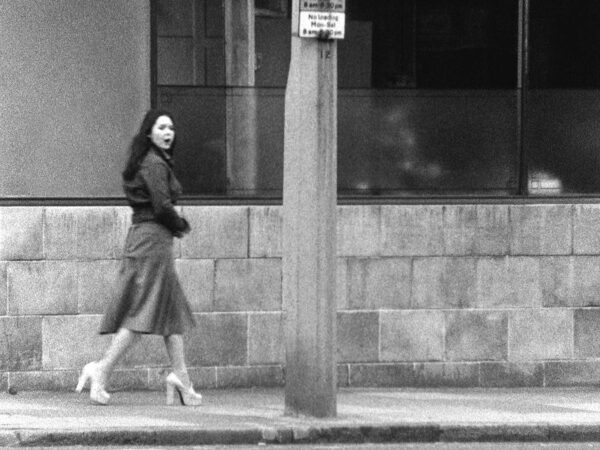

The film opens in the streets of London, with Magid rushing to his evening shift at a Pakistani takeaway restaurant. We see his shoes first, then his face—already nervous about the night ahead. The score highlights a tension that feels bigger than being late. Inside the kitchen, there is no room to breathe: chopping, frying, orders shouted, rap music blaring far too loud for the cramped space. The film is shot almost entirely in close-ups, pushing us into the chaos alongside Magid. Inspired by his music-video background, Hindman makes the kitchen feel like it might explode at any moment. Around his colleagues, Magid performs a familiar kind of masculinity. Soon to be married, the guys tease him about his fiancée and congratulate him on his “big night”. Magid plays along and jokes back casually.

Out front, the restaurant transforms into a curated display of “Pakistani-ness.” Cricket memorabilia, rupee notes, old photographs, a Pakistan flag, even a portrait of former Governor-General Quaid-e-Azam. There is nowhere to hide, but only bright lights, constant chatter, and a sense of being permanently on display. The manager enters the kitchen and abruptly changes the music to a Nusrat Qawali, further curating the environment. Kulvinder Ghir, who has played this type of traditional patriarch before, reprises the role here. And even though Magid wears a Pakistani cricket tracksuit and an Allah locket, the traditional sound feels alien to him, as he seems more at home with the hip-hop beats.

Meanwhile, Magid’s phone vibrates relentlessly. It’s Zafar, double- and triple-texting, demanding a reply. We still don’t know who he is. When Magid’s mamoo bursts in with a Bollywood wedding song, Zafar appears too, lingering behind a neon “Halal” sign. Introducing him as an old friend, Magid cannot hide the tension. Zafar’s eyes silently ask, How could you do this to me? Hurt to hear about Magid’s engagement on Instagram, he confronts him publicly. Magid can barely meet his gaze, and eventually snaps—first at Zafar, then at a colleague—before hiding in the pantry. Zafar follows.

It is only inside the pantry that the film (and its characters) finally breathes. The noise fades away, even though they are still in the same building. Magid’s face softens, embarrassment and confusion finally visible. Magid and Zafar still call each other “bro”, but their bodies reveal more. Here, Zafar is both friend and lover, more emotionally present, allowing Magid to exist fully in the moment. As a result of this comfort, Magid opens up. He defends his decision, calling it “halal dating” and “it is what it is.” But the logic collapses mid-sentence. He starts crying. When Zafar asks, “What happens?” Magid answers, “We say goodbye,” and falls into his arms.

For the first time, the camera pulls back. Their intimacy creates a small, secret world within the corners of the busy restaurant. We are left watching this private moment. Two bodies hold each other in this tiny, unfurnished closet. Just like the film ends in darkness, the audience is also left in the dark about their fate. The influence of Wong Kar-wai is clear, not only in the neon tones but also in how yearning is captured in this private, tight space. The last embrace of Magid and Zafar reminded me of Yiu and Po in Happy Together (1997), who hold each other with the same intensity despite their uncertain future.

And yet, for all its tenderness, the film feels too safe. South Asian diaspora cinema often portrays characters caught between family, tradition, and desire. Like Javed in Blinded by the Light (2019), finding freedom in Springsteen’s music despite his father’s disapproval; Jess in Bend It Like Beckham (2002), chasing her football dreams against parental expectations; or, earlier and outside the diaspora context, Sita and Radha in Fire (1996), finding joy in a forbidden love when society and marriage fail them. Hindman’s film joins this lineage, but stops short of pushing beyond it. For a contemporary queer story, it feels held back. Where is the joy? The rebellion? The characters sparking a small revolution? South Asian queer cinema deserves more than just tales of forbidden love.

That said, closets remain real for queer South Asian people—not just through family, but through community surveillance, cultural expectation, and inherited gender norms. For Magid, accepting his queerness isn’t simple. In the restaurant, a straight desi couple kisses openly, but Magid and Zafar can only show affection in a hidden corner.

Queer intimacy has long survived in the dark—in rooms not usually meant for love, in moments borrowed from a world that refuses space. But what happens to a love that has only ever existed in the margins, never fully allowed into the light? For now, the pantry remains their only stage.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #8—a tandem workshop set during Kortfilmfestival Leuven and Vilnius Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Michaël Van Remoortere.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!