To Look Inwards is to Look Outwards

Ana Gurdiș and Elena Chirilă on Tell Me a Poem

Taking us through various difficult memories from early childhood up to the present, Ana Gurdiș and Elena Chirilă’s video poem is now nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025.

It just so happens that I’ve known Tell Me A Poem co-director Ana Gurdiș for quite a while now: we met in the small bohemian office of our mentor in film school, Sorin Botoșeneanu. We’d project whatever we had filmed that week on one wall of his office, and all were welcome to join. A lesson we both learned from our beloved “Boto”, aptly put into practice in Tell Me A Poem, is that the smallest of details in a shot, no matter how shaky, no matter how clumsy, will easily gain meaning and become something personal and precious. There’s always something in there, even if we may not be initially aware of it. By looking, and by being willing to look, we’ll be able to discover it. The other director, Elena Chirilă, I had never met before this interview, yet after watching the film, I felt that I intimately knew her too; I felt, as I am telling the two, that we have been holding hands all throughout.

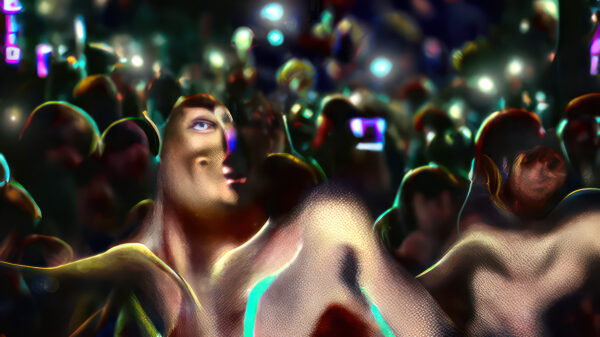

Drawing on Chirilă’s own past, relationships, and archives, the director bares her soul in this video poem, taking us through various difficult memories from early childhood up to the present. “What we did, I think, is we extracted this piece of our heart, put that on the screen, and then, we just had to go on with life,” says Gurdiș about their film. At the intersection between poetry and documentary, Tell Me A Poem is a two-part confessional and a mixture of the violent agony of ripping your heart out and the serenity that later comes with healing. Consisting of family archives, a heart-wrenching monologue, and fragments of a video diary filmed by Chirilă herself, Tell Me A Poem is an extremely personal account of an abusive relationship and of the societal expectations young women face in the Republic of Moldova, but also all around the world.

As much as she draws from painful personal experiences, Chirilă explains her intent was not to make a film about herself. Gurdiș expands: “We aimed for a certain universality. You cannot tell from the shots where exactly they were filmed. You can hear Elena talking about Iași (which is in Romania), but that’s not where you are. If you look at statistics about domestic violence, unfortunately, the same things are also happening in France, Italy, and other countries, which are often referred to as more developed than ours. That is a scary reality.”

Tell Me A Poem was made during ECHO III: For Memory’s Sake, a residency project for female artists exploring marital practices and arranged marriages in the Balkan region. Gurdiș and Chirilă hadn’t co-directed before, but, in their words, it came together naturally because they shared the same cultural space. Both coming from the Republic of Moldova and having studied in Romania, they grew up with the same things, “the same pressures about marriage, the same expectations regarding what we as women should be or do.” “You know,” says Gurdiș, “that’s what everyone asks when you go back to visit the relatives: when are you getting married? It’s what everyone is talking about. The women impose this expectation on other younger women, simply because they have gone through it [themselves], and that’s the societal norm”. This nagging presence of the topic of marriage in her own life attracted Gurdiș to the residency and the project in the first place.

“I grew up in a more conservative context, where there’s a big emphasis on religion,” adds Chirilă, “and I knew Ana would understand this organically, without me having to say a single word about it.” Originally a ceramicist and never having made a film before, Chirilă also confesses she found it helpful that her co-director had a background in documentary film and working with personal histories: “I appreciated this sensitivity of hers,” she adds. At the other end, Gurdiș welcomed the project as a chance to experiment. She appreciated that Chirilă came from a different artistic background and had no preconceived notions about what a film should look like. “In film school you’re often taught that fiction and documentary are two very separate things, and that’s as far as the categories go. But through the residency, I discovered video art and video poems, and there was a real joy in encountering so many forms of working with moving images [that defy easy categorisation]. Oh, so you can also do it like this, I thought to myself”.

Speaking of how the film came together, Gurdiș indicates she was moved by a “certain naivete” of Chirilă’s footage, which now makes up the canvas for the monologue in the second part of the film. “What Elena initially showed us—what she applied for the residence with—was this [archival] shot of a girl having her ponytail braided. I found so much breath, beauty, sincerity, and air in that image”. This shot does not appear in the final film, but it was indicative of their process: they wanted to leave behind certain expectations about form and embrace their instinct, as well as images that others might deem not immediately cinematic.

Chirilă’s video diary takes the viewer through some mundane realities: the rooftops of a patchy city, a car drive, some swans on the lake, and other unspectacular images. There’s a feeling of immediacy to these snapshots of daily life; sometimes the camera stands still, and sometimes it shakes and zooms in frenetically, betraying someone “discovering how the camera works,” as Chrilă admits. Initially, her video diary was just at the suggestion of one of the tutors at Rhea, who said it would be good to acquaint herself with the camera before the residency even started. “I think I came in with some more chaotic, more raw shots, and Ana provided a sense of order in terms of editing,” she continues, only for Gurdiș to jokingly rebut that she just knew how to use the editing software. Expanding on the amateur-like, rough aesthetic of her diary footage, Chirilă feels she was “filming [her] emotions instead of writing them down,” and filming the outside became a way to process what lay within.

“When you tell a story, you have to be sincere,” she further underlines. “I never wanted to invent things or make things more spectacular than how they happened to me. I never wanted to up the trauma or to create a tearjerker situation,” she adds, suggesting that they are happy with the fact that the film feels loose because, sometimes, too much intent or too much control may also lead to a certain ‘manipulation’ of reality. “It’s easy to bend things when you have one specific thing in mind that you want to say,” they insist. “If we had gone to these places with the clear intent of filming them and making a film, we would not have had the same material,” says Gurdiș about leaving yourself up to intuition and embracing the beauty in the imperfect shots others may have discarded.

Tell Me a Poem (Ana Gurdiș & Elena Chirilă, 2024)

The directors’ first plan was to approach the subject of marriage by looking at video archives. “Where do people film and photograph themselves the most? Weddings, funerals, baptisms, and big parties”, remarks Gurdiș about a certain Balkan ethos. “In the beginning, we looked for symbols related to marital practices, such as white dresses and the kind of Moldavian rugs used both at weddings and for decorations,” specifies Chirilă. “We looked for them within videos from our childhood, [just to see how pervasive they are].” And they are pervasive indeed—it’s hard not to notice these small details lurking in the corners of the family living room in the video montage that opens the film.

Chirilă initially hesitated in sharing her story of abuse and her experience as a young divorcee, so, at first, the idea of relying on archives also served as an alternative to opening up too much. The plan later changed, with Rhea creating a safe space for women and helping her navigate the concerns about how others may perceive her. “I feel in the beginning I avoided using my story for the film because I felt ashamed,” says Chirilă. To some extent, she confesses that she is still afraid to talk about it in Moldova because of the stigma. “People will ask you why you stayed or why you ended up in an abusive relationship, and they will also very openly suggest that it was your fault. The older generations will also blame you for having gone through with the divorce; they’ll say that you should have been more patient, or more silent,” she remarks.

Tell Me a Poem also treads on the theme of migration—from the Republic of Moldova to Romania, but also further to the West, as most of the shots of still, calm nature making up the second part of the film were filmed by Chirilă while living in France, which she refers to as her “healing place, her coming back together.” Whether it’s Romania or Slovenia, or escaping from her abusive relationship, the idea of leaving “for a better place” permeates Chirilă’s memories of early adulthood, from an affective standpoint but from a socio-economical one, too.

In addition to its obvious poetic reference, the film’s title also refers to a cultural practice most of us grew up with in the 90s and early 2000s. Ah, the thousands of Romanian and Moldavian children submitted to the same ordeal, all captured on tape urged by the adults to say some silly little rhyme. “The camera would be taken out only on special occasions. And then, because that moment was so special, you were asked to perform. They’d always ask you to say a poem for the camera,” the co-directors think back. The camera brings out a lot of roleplaying and a need to be performative, they explain, saying they were particularly interested in, rummaging through Elena’s family archives, how you could see she and her brother were treated differently, and how gender expectations are formed from an early age. “Now,” wonders Chirilă, “why was it so common that we made young girls wear white dresses and had them parade in front of the camera?”

Asked whether they feel, within the region, that the expectations society makes of women have changed from when they were little girls, the two co-directors seem to hesitate. “It is very true women have fought for much and have won much, and we are benefitting from that”, they graciously point out, stressing that they have much more economical, political, and social freedom than their grandmothers. “But, unfortunately, a considerable number of women still don’t have access to similar freedoms, while gender inequality and gender violence are still widespread and grave concerns,” says Chirilă. There are many demands and expectations that still exist: “We have things like pilates mom and the trophy wife now, but they are just the same stereotypes about women repackaged differently. The liberal-capitalist society likes to pretend it’s very progressive and that it has gotten rid of oppression, but we know that violence is not always only physical and appears in many other forms. We may like to point at communities who still have arranged marriages, but we’re hiding behind other, more hidden and more insidious gestures that still impose certain demands on women.”

In terms of what it’s like to work as a co-director with someone who is the film’s main subject, Gurdiș says it’s strange to be the “second pair of eyes.” “Essentially, you’re breaking apart and glueing someone’s life back together,” she indicates, while also stressing she’s learned to look at life as if it were a film. As she puts it, “it’s often reassuring to think that there’s a reason one moment—one ‘shot’—happens when it happens, because then it means it’s just part of the montage [of life].” Ultimately, the making of Tell Me a Poem was a healing process for both its directors. Reflecting on her experience, Gurdiș admits that in the past, she’s always chosen difficult subjects for her documentaries, “only to hide behind them.” She’s grateful to have worked with Chirilă because her story and approach helped her be more comfortable with herself and want to look inwards more. “In the end, every film we make is about ourselves, even if there are other people or other characters on the screen.”

Tell Me a Poem was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025 at FeKK Ljubljana Short Film Festival by Yan Guan Rosanna Suter, Martyna Ratnik, Miriam Vogt, Emma Marinoni, Adham Youssef, and Tinatin Kuparadze, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #5.

The New Critics & New Audiences Award is a project by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END), hosted by Talking Shorts, and funded by the Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. With the support of This Is Short.