Tripping Through Folk Horror

O, Glory!

A fun, campy homage to contemporary folk and cosmic horror.

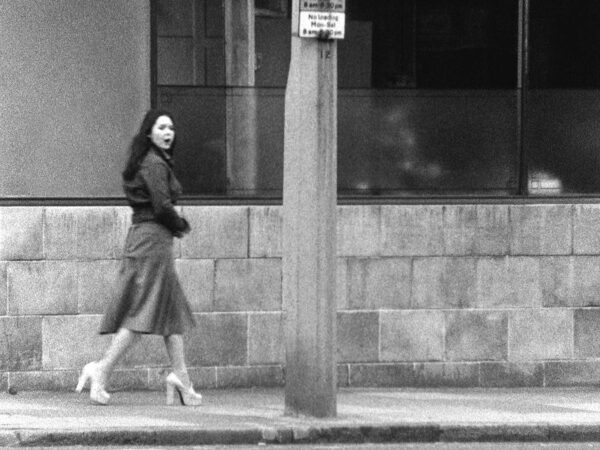

As far as its premise goes, Charlie Edward-Moss and Joe Williams’s psychedelic horror O, Glory! may feel akin to Mark Jenkin’s 16mm experimental ghost tale Enys Men (2022), which drew on the conventions of folk horror to explore the notion of thin spaces in an ancient and uninhabited Cornish isle. Filmed on 35mm and set in a remote rural area in the late 1970s, O, Glory!, screened at Lago Film Fest this year, follows Deborah, a woman who lives alone in a large country house and starts experiencing strange, ghastly visions. But as the fever dream unfurls, it soon becomes clear that what the filmmaking duo is more interested in constructing is a fun, campy homage to contemporary folk and cosmic horror.

“Folk horror” was coined by Piers Haggard to describe his own 1971 film, The Blood on Satan’s Claw, in which a malign force takes control of a rural village and its youth. Jonathan Rigby and Mark Gatiss later popularised the term in the BBC documentary Home Counties Horror (2010) to account for the genre movies of the late 1960s and 1970s that sought to explore the connection between landscapes and the human psyche. Unlike cosmic horror and its predilection for a more supernatural blend of dread, these films often featured ancient folklore and pagan practices. In O, Glory!, by contrast, characters aren’t haunted by witches or demons but by a spectre that hovers above them all.

A knock at the door announces the sinister psychiatrist Thewitt and his assistant Sylvester, who have been summoned to Deborah’s house by her brother Lochlann. These self-proclaimed “men of science” make their way into her house like malignant presences themselves, to determine whether her symptoms denote genuine madness or simply “female hysteria”. The historical inaccuracy of the term within the psychiatric discourse of the time plays up the film’s sense of camp. Unable to ascertain a diagnosis, things escalate, and the three men soon begin to succumb to madness as well. Suddenly Lochlann is naked outside; arms outstretched, his face contorted, unsure of how he got there, while Thewitt awakes with a nightmarish scream at the sight of a sinister creature in the doorway.

The men proscribe Deborah’s constant supervision and attempt to leave the property, taking her with them, but the supernatural force has its grasp on both characters and landscape. As they begin to drive away, the camera deliriously veers up to the sky as though it slipped backward, and the group awakes in a fever dream to an abundant feast. The scene, rich with Christian imagery, doubles as a flamboyant parody of religious conventions in horror films. Inebriated and with raised glasses, characters croon the line “glory, glory, halleluiah!” over and over, recalling Robin Hardy’s 1973 Wicker Man.

Charlie Ratcliffe’s soundtrack evokes the concept- and analogue-driven techniques of folk horror, imbuing O, Glory! with nostalgia. Music propels the short, dousing the proceedings in a sinister aura while also sequestering the characters’ words to an extent that prevents us from aligning with any one of them. Instead, the filmmakers ask us to focus on the film’s retro exterior and overall gaudiness. In a climactic scene that verges on parody, Lochlann challenges Thewitt to admit that he has seen something he cannot explain. Unable to account for what he’s witnessed, Thewitt raises a sofa cushion above his head, decrying that he is a man of science, and theatrically whacks Lochlann to death with it. Embracing a shaking Deborah down the hall, Sylvester whispers that he believes her now. She tells him that the phantom “came from the sky,” and we watch cosmic lights wash over the house. The screen swells into a technicolour palette beaming from the giant spinning orb that opened the film—the alien’s ship? O, Glory! accelerates straight to histrionics. Peppered with nostalgic references to folk horror, it is a perfectly calibrated blend of gothic and camp that will thrill audiences.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #2—a tandem workshop set during Lago Film Fest and FeKK Ljubljana International Short Film Festival—and edited by tutor Leonardo Goi.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!