Visible Fingerprints

Jyoti Mistry on We Come in Peace, They Said

Mistry’s films are both an intervention and an invitation. Her triptych We Come in Peace, They Said reappropriates archive footage to unearth representations of the historically marginalised.

After an hour-long talk over Zoom, I tell Jyoti Mistry that we both sat on juries in Vienna Shorts two years ago, but we missed each other. “The universe has found a way to correct this,” she smiles, and her warmth reaches me through the screen before we hang up. The South African filmmaker and academic was back in Vienna last month to present her latest work at the Austrian Film Museum.

Such a setting predisposes one to consider the intersection between institutional and social dynamics, tactfully exemplified in the three shorts that make up the trilogy We Come in Peace, They Said, giving us a clue as to why Mistry sounds so excited to meet the festival audience: “So much depends on the curatorial framing. The museum context already invites how [the trilogy] should be read, right? Are people going to respond to it as an archive project?” A few months prior, when the trilogy played at the Glasgow Short Film Festival, it was part of a seminar series at the Centre of Contemporary Arts. The metaphorical framing of a film within such institutional contexts is not that different from framing as a formal gesture: the frame always draws attention to what lies beyond it.

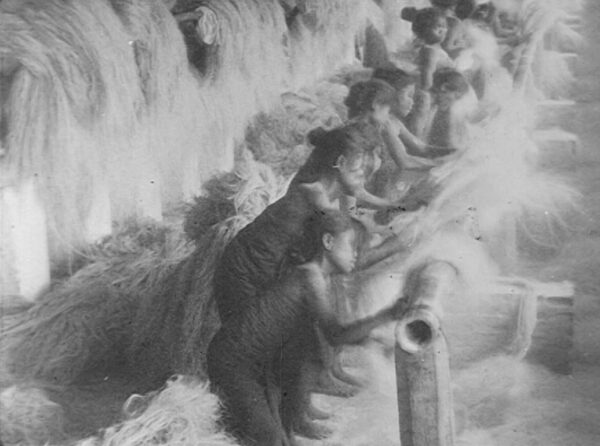

Mistry positions her work as an interplay between cinematic traditions and installation art, from her first short, We Remember Differently (2004), which weaves in old 8mm and present-day footage up until the aforementioned trilogy. Archives, particularly those of the EYE Film Institute in Amsterdam, are not only a primary source for her work but also a character she interacts with. The first instalment in the trilogy, When I Grow Up I Want to Be a Black Man (2017), has perhaps the most apparent formal dare: a split-screen of differences. One (archival) side references racial violence, and the other (original) visualises freedom as a counterpoint, while a scripted, spoken-word voiceover accompanies both images. In Cause of Death (2020), the words of an autopsy report intertwine with archival film footage and animation to expose violence against women as a structural problem.

Concluding the trilogy, Loving in Between, is an experimental stream-of-consciousness, brought together by archival excerpts and spoken word in celebration of eros in its many shapes and forms. Together, these works are paradigmal for Mistry’s view on filmmaking. Without sacrificing one’s political responsibility to the here and now, her films are both an intervention and an invitation.

You’re a film professor at the University of Gothenburg and your works have been shown at major festivals. How do you personally see the relationship between film practice and academia?

There’s something to be said about this position in different contexts, as a practitioner and scholar. Historically and institutionally, these have always been held apart, but I don’t think they have to be. There is a long history of dual occupations, but they’ve been historicised in quite specific ways. Feminist filmmakers like Barbara Hammer or Yvonne Rainer, who belonged to this particular generation of the experimental American avant-garde, all taught actually, even if we don’t think of them as attached to institutions.

Do you think it’s inevitable, especially for women, to be remembered either as a teacher or an artist?

I’ve never thought of my careers as separate: pedagogy and education are inherent to both my practice and teaching. I have always talked about them in triangulation, supporting each other. The films I make and the research I do are deeply anchored in a conceptual, theoretical, and ideological discourse that invites clear articulation. I’m saying ‘clear’, as opposed to the attitude of “I’m an artist, and I don’t want to explain what I do because it dissuades the myth of what I’m doing.” The idea of the artist as a genius is a very male concept, right? It comes from a particular historical period when mostly men were talking about themselves as artists as if they were ordained with some kind of special gift.

I don’t like to think of teaching as transient because it’s so directly impactful. But it’s a different kind of legacy compared to a film or filmography.

I also think the idea of “artistic research” is dissuading: all artists and all practitioners are doing research. They are doing the work it takes to make the work. There is a mythology around making art, and I don’t think it’s ephemeral. Of course, the process can sometimes be ephemeral, but you still have to do the work. That’s why I don’t think about teaching as a secondary thing. It seems to me that nobody lies in bed at night thinking that they want to be a great teacher but that Buddha is a great teacher. I don’t think Western culture raises you to think about teaching as an accolade, with adoration or reverence. I don’t know. How do you go about it?

As part of Talking Shorts’ criticism workshops, I have effectively “taught” at film festivals, but I wonder about the pedagogical aspect of your practice. How do you see it fit in the context of film festivals? Your films are shown at Vienna Shorts, Glasgow Short Film Festival, Berlinale, Locarno,…—all having different stakes, ecosystems, and prestige.

That’s a great question. Maybe I wouldn’t use the word ‘pedagogy’ in the context of a festival. My concern is that it assumes a certain kind of immediate didacticism in cinema. But I think about cinema more as a conversation; it isn’t driven by a programmatic purpose, but rather the possibility of what conversation means. A film opens up the space to have a right to reply. In light of my work, I always think about it like this: “These are some of my concerns. I’m thinking about them. How would I offer it to you? How would you respond to me?” It’s not something I teach because I don’t see it as something I have to give. I often approach it from a position of not knowing.

In class as well?

Yes, I’ve become much more attentive to the fact that I can’t be the knowing-speaking subject. Instead, I’m inviting. Take, for example, the title of the trilogy: We Come in Peace, They Said. I hope people recognise this phrase and still ask themselves what it means. We know what that phrase has meant in the history of colonialism, namely: “We said, we came in peace, and then we did something else…”

© Peter Griesser

What kind of themes and conversations do you find recurring in such presentations of the trilogy?

Often, we end up talking about gender or structural violence in society, which raises historical and institutional questions about power. We always assume power resides within the state, but there is also science and religion. Their narratives have all been supporting each other. Whether it’s the so-called church, medicine, or the language of science, they all have roots in the discourse of women’s inferiority. I try to open up the conversation. Do we feel the same levels of trepidation and anxiety? Are we all thinking about it in similar ways? Or hopefully, in different ways.

Even though your films work through this question, I will go ahead and ask it. You work with archival material from the first forty years of cinema, where the role of media in establishing colonial dynamics is quite visible. Where does the role of media complacency come in for you?

Wow, let’s have that as a seminar topic!

You’re right… I’m sorry. [laughs]

No, it’s brilliant—you framed it nicely, actually. It makes me think I’m more interested in mediation than media and the image and truth historically ascribed to it. Take early photographs that postulate a logic of “I see it. Therefore, I believe it”, and you have the idea of image as evidence. Of course, the image was the evidence, but an evidence that was framed in a particular way, for a particular reason. Your question is really important because we have this perception that media has always been here because it’s so ubiquitous nowadays. But it wasn’t. Gender and racial stereotypes alike emerge from images that are reproducing versions of the world that some are more comfortable with. It’s convenient, right?

Is this why you intervene in the image itself—whether by editing or animation—as visible fingerprints onto the visual archive?

That is spot on. Rather than presenting the image as given, I’m trying to interrupt it to expose the politics of the aesthetics. By revealing my manipulations to the audience, I also show the ethics I’m working with.

So, what is your process like? Since the first two films of the trilogy share the same archive source, did you start with the images themselves?

The starting point was different for each piece in the trilogy. When I Grow Up, I Want To Be a Black Man starts with an inquiry into the [EYE] colonial archive and, more specifically, the racialised images of wealth extraction. But with Cause of Death, I started by looking at the women in these [archival] images; they were always at the edges. Loving in Between emerged from an encounter with a private collection that became the source [showing images of queer desire]. Even if the vantage point for each project is different, my research is always driven by the fact that I don’t understand something and want to learn more. When making a film, I am not only satisfying my own curiosity but also negotiating it and exposing it to the audience.

This makes me think about the dynamism that illuminates the screen; the trilogy is definitely not a contemplative investigation. There’s a clear rhythm.

The rhythm is produced not only from the movement but also from the sound. When experiencing cinema, we’re traditionally trained to obsess with the ocular. But what would it mean to really listen to images? I think that’s quite exciting, while contemplation is always a silent experience.

The rhythm of your films is fast-paced. Does this have an emotional connotation?

Yes, it also testifies to the fact that there’s joy! If we think of Cause of Death showing how oppressed women are, we are not crying in the corner all the time. No, we find joy, we dance, we find pleasures. Of course, we understand oppression and we understand slavery, but we keep living as people, and there’s joy in that. Loving in Between is aware that there’s so much violence directed towards queer bodies and so much judgement towards emancipated sexuality, but also that it’s external. People who are comfortable with their sexuality are having a great time.

I asked you about the beginning of your process because the sonic and visual elements of your films are glued together so well. As a viewer, it’s impossible to tell what came first.

This trilogy is held together by collaborations with two extraordinary artists. I had worked with Kgafela oa Magogodi in 2006, and ten years later, an amazing thing happened. When I encountered the footage for the first time in the archive, I heard his voice! It was a weird experience, but then I knew that I needed to go back and work with him again. When I met Napo Masheane, similarly, I could feel the strength of her voice. In terms of the trilogy, I worked with them during the editing, but separately. Neither of them ever saw the images that I was editing because I treated my processes with both of them as sacrosanct and contained. We talked a lot and worked on the script together before they recorded their voiceovers. I then reworked these recordings a bit before bringing it all together. There was a profound level of professional respect and incredible trust involved.

Before we finish, I just want to ask about your reluctance to use any text or subtitles—not any, but very, very sparsely. Is this also part of your attempts to listen to the image itself instead of relying on the logocentric interpretation of it?

Thank you for paying attention to that. It is! I’m interested in what constitutes a radical act of listening. All languages have an amazing rhythm, but we don’t always have to understand them. There is joy and humility in working with people whose languages we don’t speak. You open up to listening in a different way, allowing yourself to trust the sonic element, to feel it and hear it. It would be beautiful if we could surrender to listening without knowing.

Mentioned Films

When I Grow Up I Want to Be a Black Man

by Jyoti Mistry, South Africa, Austria, 2017, 10’

In this split-screen film, the left side functions as a lexicon of violence. On the right, it evokes potential aspirations and ambitions of a future where the value of the Black man in society is revitalised through a lexicon of freedom. A Black man runs towards it.

Cause of Death

by Jyoti Mistry, South Africa, Austria, 2020, 20’

Women’s bodies are always at risk. An autopsy report describes the physical impact on the body that results in death but hides the structural and recurrent violence on women’s bodies that leads to femicide. Through archival film footage, animation, and spoken word poetry, an experience of structural violence against women is exposed.

Loving in Between

by Jyoti Mistry, South Africa, Austria, 2023, 18’

Political rules, religious orders, social norms, and cultural taboos control who we love and how we love. The right to love is controlled and regulated by how we live. But the erotic has the power to emancipate. With spoken word and archive sources, love is unboxed from categories in queer expression and a celebration of eros as the power to change our attitudes to life and to allow others to live their lives without judgment or prejudice.