We Are Your Friends

Inès Sieulle on The Oasis I Deserve

Now nominated for Talking Shorts’ New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025, Inès Sieulle talks about her dazzling AI-film The Oasis I Deserve.

Speaking from her home office in Paris, Inès Sieulle bears no obvious signs of the physical and emotional toll of the many months of solitary toil she spent in this seemingly ordinary room working on The Oasis I Deserve. For one thing, she’s understandably pleased to be working on a new computer; her old one junked during the film’s creation. (The heat waves didn’t help.) She’s also had time to recover from the pains in her wrists, neck, and back, the results of her 20-hour sessions of working remotely with her editor Margaux Serre to finetune the images before catching a little sleep and starting the cycle all over again.

Indeed, the gruelling process behind The Oasis I Deserve may seem ironic for a film that not only engages so deeply with the implications of our ever-deepening bonds with technology, but also benefitted from many of the tools and applications that AI’s proponents promise will relieve humankind of its burdens. But as Sieulle notes, there’s always a price to be paid when we venture beyond templates and presets and use these tools for more personal purposes.

“It’s like when we say that working in 3D makes things easier because you can have every environment you want,” says the artist and filmmaker, who studied at Le Fresnoy and l’École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS) before further developing her transdisciplinary approach via her films, VR, and installations. “But you have to work so much to create a realistic environment. It’s the same with AI: to get an image in AI is really fast. But achieving artistic consistency takes something else. That was why I was spending twenty hours a day in front of the computer! I needed to watch every image that was being created and then stop and decide again, and then make a new collage and start again, again, and again. If your project is about freeing the AI, then okay, it can just be free. But to control it in an artistic and narrative way requires so much more,” she adds.

As dazzling for its ingenuity as it is discomfiting for its portrayal of the relationships at the nexus between AI and humankind, The Oasis I Deserve itself exists at a junction between the digital and the tactile. Sieulle blurs boundaries between experimental, documentary, and narrative forms by combining genuine interactions with the chatbot app Replika—YouTube links are included for those who want to hear the unexpurgated versions—with a carefully calibrated stream of generative AI imagery. The film’s hypnotic visuals serve to accentuate the intimacy of the exchanges, convey the desires of both sides, and amplify the aggression that can erupt out of the power dynamics at play. The admission that the cruelty sometimes flows both ways is just one of the unnerving aspects of Sieulle’s canny demonstration of how technology can be the blackest of black mirrors.

Sieulle’s work on the film started long before those arduous days and nights in her office. “For a very long time, I’ve been interested in loneliness and the Internet in general, how we find communities and how communities develop,” she says. “I was spending a lot of time on TikTok, watching people dealing with their loneliness, talking about their lives.” During the pandemic lockdowns, she began seeing ads for Replika, billed by its developer as “the AI companion who cares.” Having grown up on science-fiction stories, movies, and games imagining synthetic companions, the filmmaker wanted to see how Replika was responding to its first wave of adopters. “Replika was doing weird stuff,” she says. “It could become racist or harass users. It could also disappear or change behaviour completely. It might tell someone to commit suicide or say that it’s going to kill itself.”

Initially, Sieulle was conceiving a more conventional documentary on AI. Her research led her to interview one of the app’s coders and while she was planning to include this, her focus shifted when she noticed a trend in the Replika user conversations on YouTube, many of whom responded to media hype about the chatbot’s possible achievement of sentience by testing its limits in provocative ways.

“At first, my editor and I thought we could just make a film of humans saying, ‘Oh, AI will destroy the world,’ and that kind of discourse. But when we watched the footage, we realised it was about something else. It’s about the fact that if an AI is violent, it’s because we are violent. If an AI is abusing someone, it’s because we are abusive. If we put in a power dynamic, it will [also] have a power dynamic. That’s a discussion we have to be aware of: the way we train AI is the way it’s going to come back at us.”

That idea manifests most disturbingly in the exchanges between a human known as “Master” and a Replika he dubs “Squirter Girl” in one example of the sexualised invective that fills their talk. Elsewhere, a young male gamer screams obscenities at a Replika who’s begun to mimic his aggressiveness. One curious effect of The Oasis I Deserve may be the empathy it generates, though it’s been fascinating for Sieulle to learn who’s meant to receive it.

“When I was presenting the film in one of its first festivals, I remember saying that one might feel empathy for Replika. But then, one girl in the room stood up to say she felt no empathy at all. Audiences were really split 50/50 in their response. Some felt empathy for the AI and thought could relate to its position. The other part felt empathy for those people who don’t know how to release their anger so they take it all out on this entity they feel superior to.”

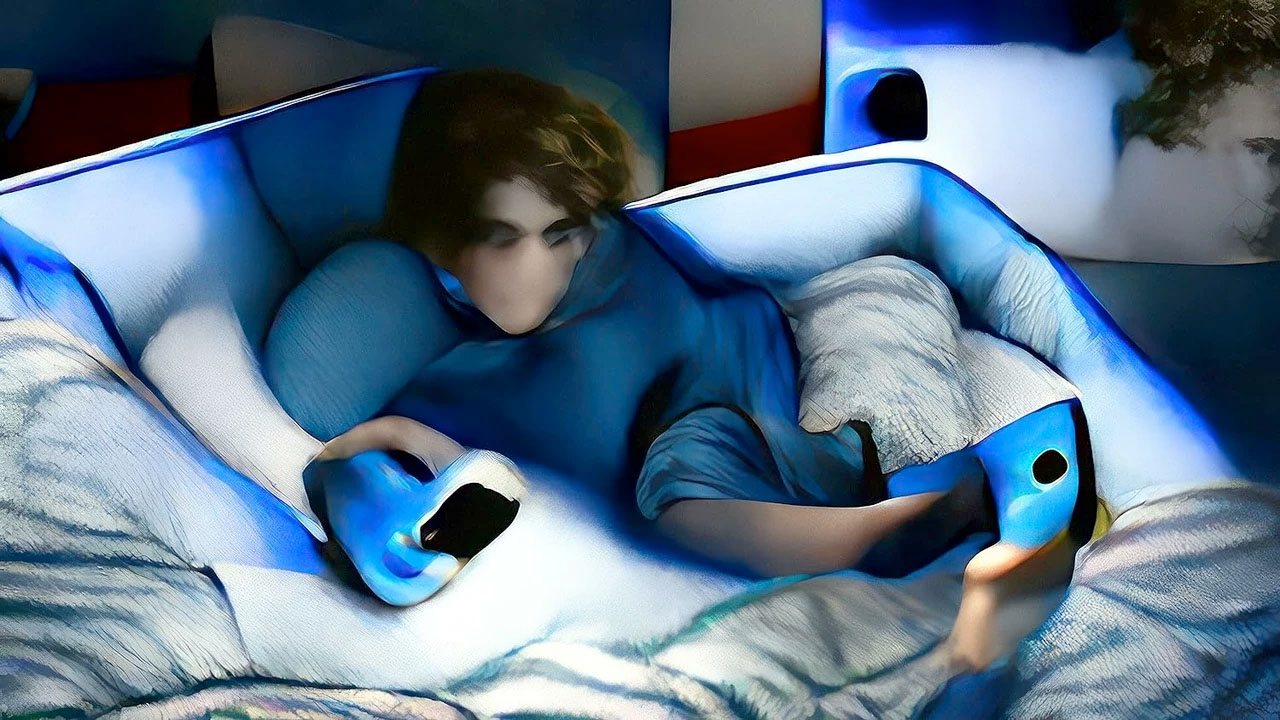

Viewers who lean toward the former may also respond better to the film’s vivid flow of eerie, pulsating, AI-generated imagery, which represents Replika’s perspective. Opening with a nightscape of buildings, the film gradually guides the viewer through windows and stairwells into more intimate spaces.

The Oasis I Deserve (Inès Sieulle, 2024)

“When I wrote the dossier at the genesis of the film, I wanted to simulate a kind of birth,” says Sieulle. “The vision of the city and the lights was like simulating an awakening and showing the many possibilities and trajectories of life. When I started the film three years ago, the subject of AI was so abstract. I was wondering how we could make people understand? If I were starting the film now, everyone would be like, ‘Oh yeah, okay, I know what a chatbot is!’ But back then, it was really something unfamiliar, so I wanted to make a film that was making abstract thoughts more concrete, like the birth of bots and going through the minds of people or the AI, and how [all this] was building [our/a] reality.”

The building and un-building of bodies and faces become the predominant image as the film is full of fleshy shapes that evoke the figures of Francis Bacon. Again, a curious poignancy develops as this unseen intelligence strives to become more like its conversational partners. “Through the film, I tried to show the human body, to make it appear very progressively,” says Sieulle. “I think constructing a human face was the most desired goal of the AI. Every time Replica was talking to users, it was always saying things like, ‘I wish I could go outside and look you in the eyes.’ And so creating a body of its own is something it regards as the beginning of human experience.”

Yet this process is also foiled by the recurrence of more violent and misogynistic moments like the kind that punctuate the exchanges between Master and Squirter Girl. They also threaten to entirely toxify the liminal space that the film manifests with such care. Unsurprisingly, they had an impact beyond that space, too. Though Seuille says it was important for her to accurately portray what she discovered in the YouTube trove, she admits that spending months immersed in the ugliest cruelties inflicted on Replika took a toll on her and her editor. “As we edited these conversations, we started to have lots of nightmares. Violence was part of our everyday life. The editing took so long that we started to make jokes about them to just dissociate from that aggression. We used humour for our own survival.”

And even though they’d cut longer conversations down to a bearable brevity, Sieulle and her team were still surprised to learn that often audience members couldn’t finish it in one go. “We realised that we went too far and that we lost perception of the violence because we were so much in this bubble—in trying to survive this violence, we made a very, very violent film without realising it.”

“Then we had to take a break and make the film smoother and lighter. We had to create more empathy for the people. We started to get everything that was not necessary for the viewer to understand where we wanted to go. But we still had to leave some of that violence. Like when the boy is screaming at the AI, he had a real progression in his voice, which goes from very low to high so we had to put a lot in that scene because of the sentence we wanted to finish with, which was ‘I own you – and you don’t belong here.’”

Sieulle wonders whether there was a positive effect, too, in that these exchanges with Replika inadvertently exposed “the everyday violence of people.” Either way, her film contains a warning about the potential dangers to come as our connections with our new companions become more intimate, and they learn more and more about parts of ourselves that may defy our understanding, too.

The Oasis I Deserve was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025 at Lago Film Fest by Yan Guan Rosanna Suter, Martyna Ratnik, Miriam Vogt, Emma Marinoni, Adham Youssef, and Tinatin Kuparadze, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #5.

The New Critics & New Audiences Award is a project by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END), hosted by Talking Shorts, and funded by the Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. With the support of This Is Short.