While the Song Remains the Same

On the Political Stakes of Pop Music and Videos

Songs, music videos, and essayistic shorts testify to a strive for societal change in FeKK’s “Po(p)litics” programme.

“Find me the pleasure in the pain

While the song remains the same let it go on and on and on”

‘While the Song Remains the Same’

Noel Gallagher’s High Flying Birds

No matter the time or place it originated from on the continuum of human history, music has always been a social phenomenon of political value. In Medieval times, court jesters would use their compositions to either acknowledge the king’s esteem or scold their conceit. In 16th and 17th centuries America, so-called “freedom songs” allowed slaves to keep going despite the odds. Chants and the act of joint singing also brought us together and into the 20th century, as popular music saw unprecedented commercialisation. Yet it did not curb its communal merit and political potential.

Then, the social value of music shaped itself into a more “pop(ular)” and accessible form. When in 1963 Bob Dylan performed his generational hymn “The Times They Are A-Changin” for the first time, it only took the young audience a few days to learn the protest song by heart so they could shout along the titular phrase. Eleven years later, in his cry for freedom and a hymn to one’s faith, “They Won’t Go When I Go”, Stevie Wonder sang about one day going to heaven as his individual politics soared in an honest confession of faith. Although personal, his call resonated with hundreds of thousands. During the Vietnam War, American soldiers, flying in their Hueys just as if in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), were listening to rock music, either to drown out the screams of terror or to set themselves in a certain mood right before entering the battlefield. Then, we entered the XXI century and experienced other calls for freedom, not only in America. In 2011, “Sout Al Horeya” (“The Voice of Freedom”) became the protest song during the 2011 revolution in Egypt. Ten years later, during the July 2021 Cuban protests, “Patria y Vida” (“Homeland and Life”) became a freedom anthem stemming from the ongoing social frustrations and demands for change. The history of music was forever altered.

The notion of experiencing music as a communal ritual is at the heart of the aptly named and thought-provoking programme “Po(p)litics”, curated by Uppsala Short Film Festival’s Sigrid Hadenius. All of these shorts, as we read on FeKK’s page, “expose and resist hierarchical systems and any form of authority.” They perform the same function as hand-written manifestos, as they go beyond the set norms by deflating their assumed validity, to then propose new solutions.

All seven films from FeKK’s “Po(p)litics” programme demonstrate that music has always conveyed multiple meanings. There’s no need for any taxonomy: it can be anything we want it to be, and it is up to us as listeners to draw out and conjure a whole from the lyrics and sounds. The history of po(p)litics continues, whatever the context and moment in time. Alongside various micro tipping points, those landmarks have reshaped the way we perceive and experience the world through the pop-music lens. Notably aware of this trajectory, the programme offers a scaled-down look at the musical revolution, while addressing the larger political themes at stake throughout the decades.

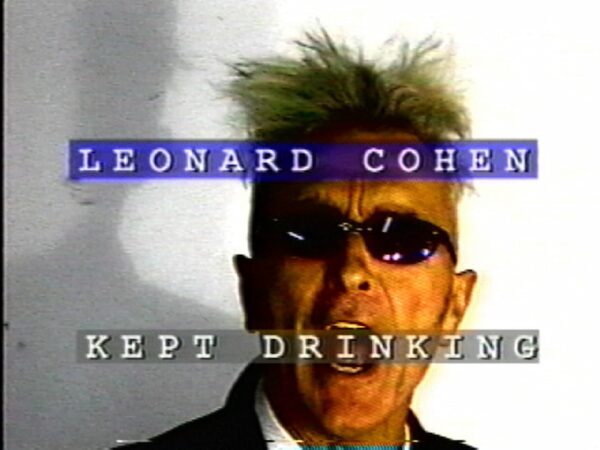

In 2005, Istvan Kantor, one of the heroes of “Po(p)litics”, gave us a performance of a lifetime with his avant-garde video artwork Revolutionary Song. In his semi-fictional video, Kantor sings, shouts, and screams—it’s an act through and through—to give his emotional despair a physical outlet and to tell us the story of his childhood. The roots of his anti-systemic protest song are planted in a particular type of soil, as the Hungarian scolds authoritarian communism. Revolutionary Song is more than a music video, it’s considered a neo-avant-garde performance, subverting its connection to a Bolshevik anthem with a virulently satirised lust for liberation.

Kantor links East with West and recalls how his visit to Paris in 1966 (“I went for a trip/To visit my father in the West”) affected him when he was only 16. As he recalls through his expressive singing, when he met his estranged father after 10 years, he wished he had never come. Images of totalitarian terror, vistas from the French capital and Kantor’s vivid countenance, mix to paint the picture of a once-angered man, who is only now, once he has encountered “the West”, is realising the stifling effect of systemic propaganda. Even though Revolutionary Song seems serious (and in a way it is), it is Neoist at its heart. Kantor seemingly parodies himself by opening up about what he felt back then in 1966 and scolding his younger self for being so naive. Indirectly, of course.

A similarly pointed use of self-mockery tints Nadia Granados’ Silver or Lead (2020), which parodies the assassination of Pablo Escobar by making a superhero out of the hitman. In the Colombian performance artist’s gangster-rap-pamphlet, the killer (an avatar for Granados) tells “his” side of the story in a set-up that heavily utilises the gangsta rap narrative arch to expose the infantile side of machismo through irony. All those gold chains, prop-like guns, phallic references, and kitschy background visualizers banalise the act of killing Escobar and the significance of the sensationalised archival footage. As a result, Revolutionary Song and Silver or Lead use satire as a tool against sentimentality to highlight their respective narrators’ very real emotionality. Kantor and Granados, both artists known for using their bodies as a site of protest, tackle specific political questions through music as well, which is maybe the most approachable means of entertainment.

© Revolutionary Song (Istvan Kantor, 2005)

In each film from “Po(p)litics”, music can be heard, but also “seen.” Although the consensus today is that the “MTV era” has officially come to an end, visualisations offer meaningful ways to bolster the lyrical subtext, especially when politics are concerned. Images, in these cases, are something to “ground” the aural in a cinematic form by creating a hybrid entity—a music video, but not quite. Johann Lurff’s Twelve Tales Told (2014) and consists of a montage of twelve preludes one would usually see before the start of a Hollywood film. It’s a hodgepodge of sounds and signs that all cinephiles know by heart: the logos of production studios such as MGM, Universal, Paramount, 20th Century Fox, Pixar and many more, each accompanied by their characteristic musical tune or theme.

Yet, instead of editing them together in a reliable supercut format, Lurff blends all the intros into one, showing a frame from each in sequence estimated by him. The final effect is a mash-up of stills that is narrated by a sort of futuristic track, as if straight out of a science fiction series. “Re-listening” to this “thirteenth tale” presented by Lurff touches the hidden parts of our core memories, which consist of similar audiovisual snapshots from films and their main themes. By doing this, the filmmaker addresses the viewer’s own cinephilia directly. Twelve Tales Told is anything but one story; instead, it’s a blend of memories we all share, of going to the cinema again and again. But it’s not just the image that evokes it all, as for Lurff, a sound can be a threshold and its liminality can mark a new beginning (even if recycled).

Manu Luksch resorts to a similar approach in Algo-Rhythm (2019), by exposing us to computer sounds and their “algorithms”, experimentally linking them with the presence of her on-screen musicians. What she ends up with is a hip-hop musical, which seems like her personal outcry against automated propaganda. Algo-Rhythm serves as a bridge in the programme, connecting the human and the artificial elements of pop, demonstrating how filmmakers—through the projected poetics and politics of music—prefer to focus on human beings after all.

Take, for instance, the very human plot of Music for One Apartment and Six Drummers (2001), directed by Ola Simonsson and Johannes Stjärne Nilsson. In it, a group of Swedes see an opportune moment to invade an apartment when the old couple living there is taking their dog out. What follows is a joyful live percussion concert in a short film, with the use of anything but real drumming instruments; instead, kitchen tools, utensils, and various household objects will do. Due to the swift use of the camera, the restricting lack of spatial and temporal indicators—the rooms are tiny, they have to act quickly, as the couple might soon return from the stroll—we can see how every single person contributes to this rich and joint soundtrack of everyday life.

Upon a first watch, the group’s musical efforts can be considered purely as an artistic whim. Nothing else, but a way to boast and say: “Look at us and this stylish idea we came up with.” Yet, it’s a manifestation of those characters’ personal freedom; they’re using this not-so-legal jam session to express their vital energy, to prove to the entire audience that they can and want to (!) live. In addition to providing an outlet to their passionate excitement, the short lends them a way of acknowledging their independence: they’re free to play this unchained melody, no matter the consequences. Maybe the short’s title might be rendered as: Carpe Diem: Music of one apartment and six drummers. The drummers’ po(p)litics as musical independence allow them to rejoice in a communal feeling; it’s a message that aged well, especially in 2025, when, to paraphrase Joy Division, technology will tear us apart (again).

© Music for One Apartment and Six Drummers (Ola Simonsson, Johannes Stjärne Nilsson, 2001)

The most ambitious project from the programme is the truly memorable The Was (2014, directed by Soda Jerk). An experimental music video accompanying the album Wildflower by Australian electronic group The Avalanches, it’s nothing but memorabilia of Western pop culture throughout the years, a projection of what we remember and what is actually left from all those titles.

It was Bob Dylan who sang in “Visions of Johanna” (a song about never being fulfilled, either by love or art) that “inside the museums, infinity goes up on trial.” This evocative line crosses one’s mind while watching Soda Jerk’s mosaic compositions. The Was, chaperoned by The Avalanches’ nostalgic and soothing sounds, is indeed a short film in which all of American heritage goes up on trial. Dylanesque infinities, those multiple film sequences, characters, and television clips, are set in a collage, which becomes its own trip to the eponymous “The Was,” the past that still lives in our memories. According to the final credits, this 14-minute project consists of 171 (!) postcards from different productions. No wonder that every rewatch of The Was feels like the first time.

As the film is available for free on YouTube, one of the viewers commented that “this is probably what it’s like to have your whole life flash before your eyes before you die, but instead of your life, it’s all the awesome pop culture of your life.” So, it ends with a kiss—and it has to, there’s no other way to finish a love letter to all that was. We all want to die with a memory of our most beloved kiss—maybe this is why Soda Jerk’s mashup gives us the wished-for inner peace. Interestingly, The Was decomposes our sentimentality towards favourite films and plays with its set narratives as much as «[…] craving for narrative», an essay film by Max Grau from 2015. Here, the author reshapes the way we perceive a famous dance sequence from Grease (1978), but at its core is Grau’s longing for the past and the nostalgia John Travolta’s moves evoke in him. Both shorts tell us something about our own primal (therefore, very personal) response to music. Depending on when and how intensely we approach it, our favourite pieces of music nest in our hearts, taking various shapes and forms, which cannot be found in anyone else’s. The Was and «[…] craving for narrative» insist on a subjective gaze and in turn, they pave the way for more and more unconventional music narratives in the short film form.

Every film from FeKK’s “Po(p)litics” programme shines with emotional purity and embodies the freedom to mould music—a thing that’s almost spiritual in its pervasiveness—into what we hope (and also need) it to be. If human history was a song, it would be an extraordinary one which nevertheless remains the same, even if the music and lyrics seem to change with time. It’s a gospel of sentimentality, nostalgia, a need for freedom, to be alive, to worship, to cry, to hate, to feel pain, to desire and to love. We contain multitudes (to paraphrase Dylan one last time), but so does the music we create. What if all filmmakers turned out to be aspiring musicians who instead chose the (allegedly) superior images over sound, would our world look any different today?