Who Rule The World?

Sisters

Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival’s Grand Prix eloquently highlights the filmmaker’s grudge against patriarchal, male-dominated societies. Rightfully so.

The Balkans are a peculiar region. Situated somewhere between the progressive Europe and the traditional—to the point of fundamentalism—Middle East, people from the area always exhibited an identity crisis due to being perpetually “in the middle” of these two worlds. Katarina Kukla explores an aspect of this problem by focusing on the issues women who want to break free from the chains of patriarchy experience in present-day Slovenia—a setting that the filmmaker herself describes as post-patriarchal.

The story revolves around three modern-day “virđinas”—sworn virgins, tomboyish young women—Sina, Mihrije, and Jasna, all children of immigrants from ex-Yugoslavia, living in a small traditional city in Slovenia. However, their lifestyle is nothing like it: they wear baggy clothes, tape their breasts to hide their femininity, train in kickboxing, and regularly get into fistfights with men, particularly those who seem eager to offend them for being so different. Above all, they live by their Ten Commandments: rules that set them entirely apart from what is considered “normal” in the region for women their age. The sum of their mentality and overall behaviour results from following these rather intense guidelines, all of which are, essentially, a reaction to society’s norms.

Their lives are not easy. They have no other friends and are not involved in romantic relationships, ultimately spending all their time together. The only one with a real job is Jasna, who works the bar at a club she hates. The trio seems to get no support from their parents, who do not play any part in their lives. However, the three girls do not allow other people to feel sorry for them, nor do they feel sorry for themselves—they are no victims of their circumstances; everything they do is by deliberate choice.

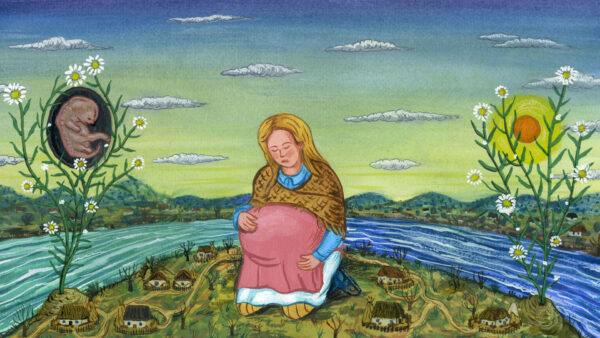

The ten self-imposed commandments embody their resolve to escape all rules the patriarchy and the small town’s mindset dictates—their attitude being a direct counter-action to both. When they witness a man beating a woman (who appears to be his girlfriend) in the middle of the street, the trio looks at it as a blueprint for all romantic relationships: never a choice—which woman would be with a man who beats her in the middle of the street?—but a sheer construct enforced by a society that expects all women to find and marry a man, even if he acts violently. Later in the film, the three watch a baby rocking in a cradle. The scene highlights their thoughts on motherhood. Sina departs almost immediately, Jasna lingers for a bit before she goes, and Mihrije stays for quite a while and then ultimately leaves, too. None of them exhibit the usual adoration for babies that everyone expects from women: motherhood is the continuation of the aforementioned type of romantic relationship and, thus, not an option.

Considering their attitude marginalises them, Sina, Mihrije, and Jasna are forced to become warriors to survive. They train in kickboxing every day and take good care of their body, avoiding alcohol and hard drugs—a stance that alienates them from their peers even more, since in the Balkans it is common for both young (and old) people to drink a lot, and drugs (though illegal for the most part) are quite easy to find.

Sisters is a polemical film. Katarina Kukla holds a grudge against the patriarchy (and the ways it limits women) as well as the mentality of the small town (which does not allow any effort for change) and men (who are presented in the film as the primary source of all the issues faced by the titular sisters). The three girls embody this line of thinking, though the group’s leader, Sina, is more intently set on their “war against the world”, frequently pulling the other two with her in actual fights against men. Kukla’s implemented contentious approach is mirrored directly in Sina’s behaviour.

Sisters

In a somewhat disillusioned twist, the fact that all of them are willing to fight does not mean they always win. On the contrary, they frequently get beaten and experience demeaning behaviour. What makes them winners, however, is that they keep fighting, no matter how many times they lose. Kukla also makes evident that a helping hand is always welcome, as the scene with the basketball game illustrates. If not for a “deus ex machina”, that confrontation could have ended in a true tragedy. The scene introduces an ally, finally: Fantasy, a trans woman living in the neighborhood. Though exceptionally brief, her presence in the film is quite significant, as it strengthens the representation of women. It proves that the protagonists are not alone in their quest, even though they might feel that way. The grateful smiles on their faces upon their meeting with Fantasy speaks volumes.

Peter Paunovic’s camera realistically captures the small Balkan city in mostly grey tones, intensified by the almost always cloudy sky. That the sun is only shining when the three girls are alone emphasises the film’s general idea: their relationship is the sole source of light in an otherwise rather dark environment. Katarina Kukla’s background in directing music videos is visible in many scenes with intense colors (mostly red hues, neon lighting) and rather frantic editing, both approaches humming on the medium’s aesthetics. The loud Balkan soundtrack—composed by Kukla herself—highlights the “in the middle” position mentioned at the beginning of this text by combining electronic and oriental influences. Compared to the rest of the visual form, these segments might seem out of context, but they provide much-needed relief from the pervasive bleakness.

Sisters, which won Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival’s Grand Prix, quite eloquently highlights Kukla’s grudge against the patriarchal, male-dominated societies—rightfully so. The need to change the rules that support this overall mentality that trivialises women (recognising them solely through their roles on the side of men as girlfriends, wives, and mothers to their sons) is emitted from every action and word of her heroines and in every frame of her mostly bleak and pessimistic film. Change, so the director states, will only come through sacrifice (of romantic love, of motherhood, of peace). Simultaneously, she also offers a ray of hope, stating that finding people willing to follow the same path can significantly ease the burden of self-sacrifice; the three girls’ relationship ultimately celebrates sisterhood and female friendship.

There are no comments yet, be the first!