A Christmas From Hell

Zima

Through sketch-like animations, Tomek Popakul and Kasumi Ozeki skilfully capture teenage rage and rural isolation in contemporary Poland.

Anka spends the winter saving unwanted kittens and secretly fantasising about Jesus. Her hometown, a Catholic fisherman village in rural Poland, does not offer much for a teenage girl. On Christmas Eve, though, an eerie legend comes to life and challenges the natural order of things.

This animated short film by Tomek Popakul and Kasumi Ozeki is as much a coming-of-age story as it is a twisted Xmas tale with a revenge plot. Inspired by Popakul’s own memories of growing up in a similar setting, Zima is a patchwork of several different narratives, all taking place in the snow-covered scenery surrounding the village.

It is not the first of Popakul’s films to deal with adolescent themes. His previous shorts, Ziegenort (2013) and Acid Rain (2019), are both about young people living in the peripheries of society. Loneliness, anxiety, and the desire to connect with other people are the foundation of these stories, each imbued with an uneasy atmosphere that is hard to shake off. The animations allow for a great deal of weirdness, and a generous dose of magical realism is used to emphasise the things that are simply indescribable, such as an acid trip in the rain or a teenage boy who is quite literally a fish-out-of-water.

In Zima, however, the symbolism is more politically charged than in Popakul’s earlier coming-of-age works, merging religious icons with uncanny folklore. The various themes and plotlines that constitute the film make for a somewhat tangled story that might leave the audience grasping for a connecting thread. Scenes unfold independently of each other, and the soundtrack varies between punk rock, piano tunes, and organ solos. The result is a rowdy montage-like assemblage, repetitively disrupted by silences and sudden moments of calm, as though the film itself needs to catch its breath occasionally. It refuses to follow conventional narrative rules, and somewhere throughout its runtime of nearly twenty-seven minutes, the viewer will do best in just accepting that. Does it work, though? Perhaps not flawlessly, but disobedience is also the main appeal here, possibly even the strand that binds everything together.

Zima opens with a heavy metal track by the post-punk band Godflesh. A cat is giving birth. Her babies are dramatically falling through the void enwrapped in what appears to be blood-red wombs. A short moment later we witness a group of kittens again, just this time they are not infolded in a womb, but rather a trash bag about to be thrown into a river. This opening scene, which resembles a music video, establishes the asymmetric relationship between humans and animals in Popakul and Ozeki’s winter land. Anka manages to stop the attempted feline murder, and the cats are ultimately shipped across the water and left on an isolated island. What could be the beginning of Lord of the Flies: The Kitty Version does, however, turn into something weirder still.

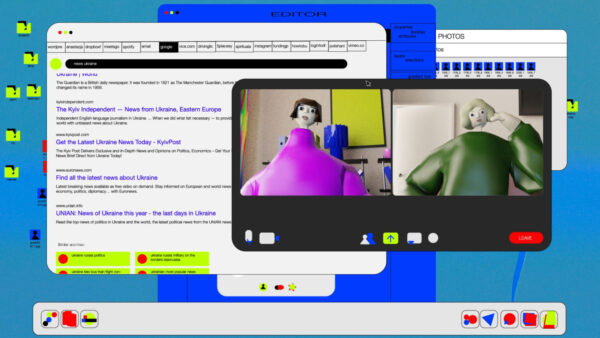

Through sketch-like animations, Popakul and Ozeki skilfully capture teenage rage and rural isolation. Humans, animals, and landscapes are mainly in black and white, with red shades to vividly illustrate blood and fire. In an interview with Zippy Frames last year, Popakul revealed that the character animations had to be adjusted to his “poor drawing skills” and difficulties with maintaining the proportions of the faces in each frame. A certain line-crookedness needed, therefore, to be turned into a charm. This results in scenes that recall aggressive notebook scribbles, contributing to the rebellious tone that saturates the film.

The rough animations and narrative unruliness capture the frustration that many young Poles are currently experiencing, given the country’s immense social and political transformation. During the last decade, national politics has been marked by resentment of the EU and disagreements over policies that concern abortion rights, the LGBTQIA+ community, and migrants. Though Zima never positions itself as explicitly political, the polarisation between traditional and progressive views is tangible. Yet here, the old and the new are contrasted through the treatment of domestic animals.

“Dogs should not eat vegetables,” Anka says to her father who has just brought his dog some leftovers. The canine—named Diablo, as his kennel suggests—is chained to his hut and left outside in the cold. “Yeah, whatever, look how he is eating,” answers her dad. Young people and animals share the experience of being disregarded by the adults in the village. Most likely because the older generation is occupied with drinking, consequently leaving the teenagers to themselves. And what do unsupervised Catholic kids do? Well, sneak into the church to drink communion wine and eat wafers, of course.

For Anka, however, consuming the body of Christ has a special meaning. The film’s first what-the-fuck-moment features her secretly making out in the woods with a loinclothed Jesus. When they are busted, the Lamb of God awkwardly runs away and disappears through a tree trunk, presumably into another dimension.

This love affair, which screams of both sexual awakening and frustration, is also another reminder of the contrasts between the old and the new. Poland might be one of the most Catholic countries in the world, but the Church is currently experiencing a crisis, with young people turning away from religious practices in droves. This Jesus figure is most definitely loaded with Christian symbolism, but to a teenage girl who does not really connect with any of the boys in her village, he is also an object of desire. And like a fairy prince, spirit, or creature of the forest, he takes on a mythological quality.

Religion and folklore collide as the electricity unexpectedly goes out. While the villagers are seeking refuge from the cold and pitch-dark, someone unfortunately brings up a legend: it is believed that, at midnight on Christmas Eve, animals can speak with human voices. When the clock strikes twelve, a choir of human-animal voices rises outside. But it quickly becomes clear that pets do not have especially nice things to say to their masters. Cast-away cats and chained dogs are unhappy with the way they have been treated. The time for their vengeance has come, and the Christmas party devolves into a nightmare.

In its final moments, Zima becomes a combat film with an intense escalating climax. The viewer, who might have been confused as to where all the different layers would ultimately overlap, is rewarded by Popakul and Ozeki’s impressive visual language. Balancing emotional coldness with gentle warmth and care, the film is a messy but sensible testimony of generational shifts and human compassion. But grasping all this might call for more than one watch.

This text was developed during the European Workshop for Film Criticism #4—a tandem workshop set during Filmfest Dresden and Vienna Shorts—and edited by tutor Anas Sareen.

The European Workshop for Film Criticism is a collaboration of the European Network for Film Discourse (The END) and Talking Shorts, with the support of the Creative Europe MEDIA programme.

There are no comments yet, be the first!