Between Paradise and Perdition

Tomek Popakul and Kasumi Ozeki on Zima

Now nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025, directors Tomek Popakul and Kasumi Ozeki discuss their dreamlike animated short about life in a Polish village, where tenderness and cruelty exist in equal measure.

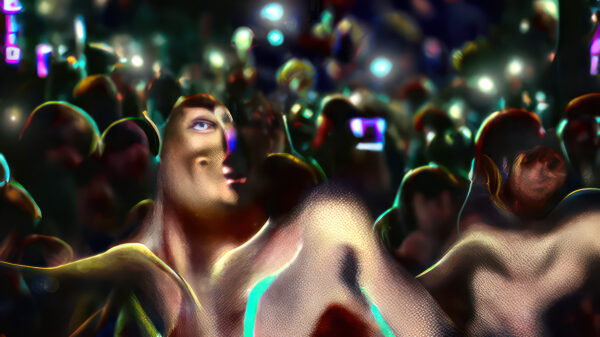

Everything is fluid in Zima. Strikingly animated, with coarse and broad strokes that can suggest a myriad of things, shots and scenes blend into each other according to some dreamlike logic, as if the directorial duo Tomek Popakul and Kasumi Ozeki tries to convey everything at once about the multilayered life in a small rural Polish community. Their magic realist film is all about the possibilities and pains of coexistence, highlighting how animals and human beings alike struggle to find ways to live together peacefully. In the midst of this wintery environment and on the cusp of Christmas Eve, a teenage girl tries to save some unwanted kittens. Her merciful mission sits in stark contrast with the more cruel tendencies of other inhabitants to neglect their animals and only fend for themselves. Ultimately, it all boils down to survival in Zima’s isolated village, a fictionalised depiction of the place where Popakul grew up.

The Polish animator has turned to his past for autobiographical elements before: his short film Ziegenort (2013) is an aestival story about an anxious teenage boy from the titular fishing village, who identifies with the fishes he tries to reel in. In them, he sees fellow victims of life’s alienating conditions, acknowledging how they’re also stuck in an oppressive environment, perpetually gasping for air. It’s the same feeling that prompts the teenage protagonist of the psychedelic coming-of-age story Acid Rain (2019) to escape her home village and strike up a peculiar romance with a drug dealer.

There’s an undercurrent of emotional sincerity that informs the particular surrealist feel of all these shorts, through which we can see the director’s personal connection to the material he has brought to life with his ever-evolving animation style. It’s as if Popakul and Ozeki here have found a way to externalise the most intimate and painful feelings that arise on the verge of adulthood.

“As they say, the first album of many bands is often the best,” Popakul explains over Zoom, commenting on the autobiographical elements in his latest free-flowing, kaleidoscopic film. “This is often the case, as the band has been working on the [same] material their entire life. So yes, it’s kind of natural that memories and experiences from childhood and adolescence shape you as a person and as an artist. I don’t think it’s intentional here, but with Zima and my first film Ziegenort, I refer to memories from my village, basically creating a twisted version of the environment I grew up in. Even though the film has a surrealistic quality, some scenes and characters might still be recognisable for my friends and family.”

Zima is animated mostly in black and white, with the occasional expressive streaks of deep reds, and the atmosphere gradually turns more haunting and oppressive. Danger looms in this remote village, where animals, if abandoned in the forest, turn into mythical beasts seeking revenge. While the eerie setting suggests a reckoning with the director’s own past, Popakul stresses that the film was made out of endearment, not resentment. “I really like my village,” he adds. “I think it’s a magical place.” He also admits there are moments in the film that can be quite scary, but they, too, are based around some of his own memories of winters spent in that place.

While Ozeki and Popakul have worked together before on Acid Rain and The Moon (2021), Zima marks their first collaboration as co-directors. “The story itself is really Tomek’s,” Ozeki explains about their creative team-up, “but on an emotional level, I see things in the characters that I also want to express about my own life and my own being. Tomek and I can talk very deeply about all the layers that these characters carry within them.” Popakul adds: “Kasumi has the ability to look at the narrative from a certain distance, which gives her a totally different vantage point on the material.” In particular, he said the film benefitted from their two perspectives, since “it was easier for her to see Zima as a film, and not as a story with a lot of personal and emotional attachments. She helps me to not only think of the humans in the film as real people, but also as fictional characters that need to be believable for the audience. That helps with finding a more sensitive and empathic approach to the story we’re telling.”

What’s so alluring about Zima is its mosaic-like structure: a roaming narrative that switches its focus between the humans and animals inhabiting this fictional universe. Fitting for a story about the (im)possibilities of coexistence, Popakul and Ozeki operate on a cosmic and personal scale, often taking a bird’s-eye view to interrogate the social contract that informs the behaviour and traditions of an isolated community. “What I like about my talks with Kasumi,” Popakul continues, “is how we observe other people and analyse their behaviour. You can call it gossiping, but it’s more like dissecting family structures or sensitive situations that show a deeper layer of connection between people.”

For both directors, it was essential to avoid judgement on the many flawed creatures (human and animal alike) that live in and around the village. Popakul shares that one of his own guidelines was to “try to have empathy for all the characters that inhabit my fictional worlds, even the ones we might perceive as bad. Just to say that someone is bad or evil doesn’t help you to understand or connect with this person.” Empathy plays a crucial role in Popakul’s approach to filmmaking, and it stretches to the real world. “For example,” he says, “if you see Donald Trump on the news, you can automatically assume he is an evil person, which makes the people who vote for him evil as well. My first reaction, then, would be to be outraged, but on second thought, I have to consider that the many people who have voted for him aren’t all evil—they just think differently than me. It can be hard to understand, but pushing myself to try to walk in somebody else’s shoes is very important to me.”

Zima (Tomek Popakul & Kasumi Ozeki, 2023)

When I mention that this coexistence of good and evil within every single human being reminds me of the work of David Lynch, an excited Popakul jumps out of his seat and reveals an Eraserhead shirt hidden underneath his sweater. “Oh, wow, yes,” he exclaims, “Lynch was a big influence on me. As a matter of fact, I met him for a very teeny tiny bit of time. We exchanged autographs as a joke, and I left him with his coffee. I’m a huge fan of his work. What he gave me was this bewilderment about the world and the people within it: are they good or evil? And is the world a prison or a paradise?”

In the case of Lynch, who at the time of recording this interview had passed away only a couple of days prior, the answer to the above questions would always be “Both”. The greatest extremes always cohabit; Lynch’s worlds are both dreamlike and nightmarish. “That reminds me of a friend of mine,” Popakul continues, “who is a huge film geek and once put himself on a marathon of Werner Herzog and David Attenborough films. He liked to observe how they both portrayed the jungle. For Attenborough, it was all peaceful harmony and paradise, with the animals cooperating and feeding each other, while Werner Herzog could only hear the screams of the creatures that were dying in agony and killing each other.” When I ask Popakul if he sees animation as a way to escape such kind of binary thinking, his response is frank: “I would generally try to avoid such big words because I don’t really think that what I do is the result of some kind of mission. But yes, this coexistence of two extremes is very important to me. I remember the working title of Acid Rain was Heaven and Hell. So far, the films we have made are about these extremes bleeding into each other.”

Zima’s fluid animations seem to reflect this non-binary mode of thinking, but for the directors, the film’s form is not a direct product of conscious decisions. “Creating the visual style of Zima was a very intuitive and spontaneous process,” Popakul acknowledges, admitting his background in 3D animation enabled him to start with the technical angle and be very particular about the camera work and framing. As a result, many of the creative decisions had to do with workflow. He gives an example of how it was “easier to use these kinds of fluid strokes with a brush because they can convey multiple things at the same time, whereas a digital composition would require a very exact arrangement of millions of polygons.” The search for a process that was both adequate to the work-load and expressive in itself resulted in the rather indescribable look of Zima. Popakul calls it “poetic, but not in a cheesy way.” He then adds: “With poetic, I mostly mean something less obvious and rigid.”

This versatility also manifests itself in the eclectic soundtracks of Popakul’s films, which boast a wide range of musical styles and sensibilities. Zima alone already combines spiritual organ music, grungy rock, and a powerful industrial track by Godflesh. “I’m quite nerdy about music,” Popakul declares. “I rarely watch films, but I listen to a lot of music.” It’s no surprise to learn that oftentimes, when conceiving a new film, the music comes first, and the story follows. “Music sparks my imagination, forming the seed of the idea that will come to fruition later. Often, I already have a full playlist in mind. In the case of Zima, we managed to incorporate 90% of my wishlist into the film.” Unconsciously, working with music on such an emotional level is also a way for Popakul to retrace his childhood memories of listening to his father’s record collection. He recalls making drawings based on each track of the album playing. “I remember doing that to the music of King Crimson and Duran Duran; Listening to that [kind of] music and daydreaming, while drawing, was a way for stories to arise in my head,” he admits.

In a sociological sense, the many conflicts that arise in Zima can be read as a fierce commentary on contemporary Polish society. Environmental concerns, spiritual crises, and generation divide frame the tense narrative, but Popakul and Ozeki stress that their work is more than just a political critique of what they observe in their immediate surroundings. “Again, it boils down to empathic and non-binary thinking,” concludes Popakul. He agrees that all these concerns are part of the film, but it’s not necessarily the point of Zima. “It’s easy to condemn and attack certain institutions and dynamics, but it’s much harder to somehow place yourself within them. And I wanted to do exactly that, instead of taking a side or mocking others who do. I just want to show how all these layers overlap, without immediately forming an opinion about it.”

Zima was nominated for the New Critics & New Audiences Award 2025 at Vienna Shorts by Mac Andre Arboleda, Daria Janke, Claudius Kesseböhmer, Antoni Konieczny, Marcelina Leigh, and Ebba Yttermyr, the participants of the European Workshop for Film Criticism #4.

The New Critics & New Audiences Award is a project by the European Network for Film Discourse (The END), hosted by Talking Shorts, and funded by the Creative Europe MEDIA Programme. With the support of This Is Short.